The connector: Colin Coleman at the South African headquarters of Goldman Sachs. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Colin Coleman doesn’t recommend radical measures to jolt South Africa out of recession. That’s not surprising.

He has been the boss of Goldman Sachs in South Africa for 18 years; like most of his peers in the stratosphere of global capital, he wants a leaner, fitter state and policies that spur job creation. Coleman argues that a public infrastructure spending programme should be funded by savings in the public sector. But unlike many of his peers, he doesn’t want a corporate tax cut: tax incentives, he says, should be targeted to labour-absorbing industries.

“Now is not the time for economic actors or the public to panic,” he tells me in his wood-panelled Sandton eyrie. “We need to engender stability and confidence, and slowly work our way back to 3% trend growth of the last 25 years.”

Coleman is not your average investment banker. He has a struggle CV and commands the respect of many ANC policy gurus, not least the president. Cyril-bashing may be in vogue, but Coleman won’t bash. He believes Ramaphosa is uniquely equipped to guide South Africa out of its morass.

“Cyril has the potential to lead South Africa in a masterful way, just as he did, I believe, with [Jacob] Zuma’s recall. I think he knows what to do. The judgment is about which battles and in which moments he should choose to take the steps he needs to take. One has to respect his judgment on the political space he has available.”

Ramaphosa and Coleman have known each other since they shared United Democratic Front platforms in the mid-1980s, when Ramaphosa led trade union federation Cosatu and Coleman was a National Union of South African Students (Nusas) leader. They had more contact at the talks about talks before the Convention for a Democratic South Africa, when Coleman represented the Consultative Business Forum (CBF), and then at Codesa itself, and then as business heavyweights.

Both men are rich enough to believe in the magic of the free market and smart enough to grasp the urgency of socioeconomic justice. But selling those two principles in one package is becoming tough. The likes of Ramaphosa and Coleman are centrist thinkers in a bifurcating country and a polarising world.

But Coleman’s ability to intermediate between tycoons and politicians is useful. For one thing, he has helped to create the Youth Employment Service initiative, a huge business-funded programme to bring the youth into the job market.

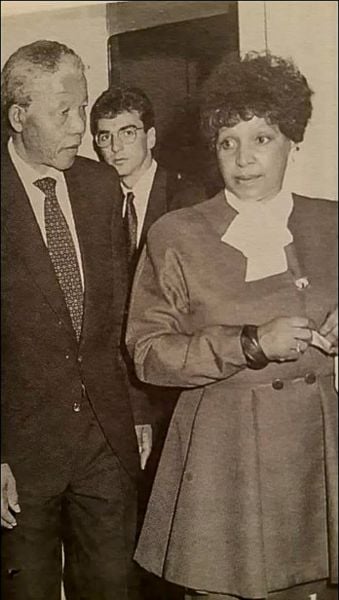

Colin Coleman escorts Nelson Mandela and Winnie Madikizela-Mandela into the Carlton Business Summit in 1990, where Mandela addressed 300 chief executives

“We launched it in March with the president, with the target of getting one million interns aged 18 to 29 into businesses over three years, or 330 000 interns a year, doing one-year paid internships. And the government is gazetting a set of incentives for businesses to take people in.”

The initiative plans to build 100 township hubs, for R5-million each, to train and help job seekers. “The idea is to bridge the worlds of the unemployed and the employed. Businesses have committed to about 50 000 internships already, so it’s out of the starting blocks.”

But the real engine of jobs growth is investment, which is throttled by policy uncertainty. “We think there’s something like 0.5 percentage points in GDP [gross domestic product] lost to policy uncertainty on mining and land.”

Coleman produces a printout of Ramaphosa’s article in the Financial Times on the land issue — and reads aloud the part about how an amended property clause would continue to prohibit the “arbitrary deprivation of property”.

Fair enough, but you can’t pass laws with opinion pieces.

“If what he suggests will actually be contained in the amendment, everybody will relax. He’s saying that the sanctity of property will be one of the things that the amendment will clarify — but will it actually contain or dilute that clarity?

“What the president says carries great weight, but once the text has washed through the parliamentary process, since they need a two-thirds majority, the question is whether his version will get past the party alliances they will have to build. So the markets and the public want to see the legislated text in black and white, or there will continue to be uncertainty.”

Mining policy is just as critical, he says. “It has a multiplier effect into manufacturing and into the families of workers. So the current 400 000 mining jobs affect a significant multiple of that number. And if you have a teetering industry and then want to have a free carry [a proposed 10% royalty to be shared by workers and neighbouring communities as a condition of new mining rights], which dilutes the return on equity, you’re effectively pushing an industry over the precipice.”

Sooner or later, Coleman argues, the public sector wage bill has to stabilise. “It has been on a consistent 2%-over-inflation trajectory for many years. It now costs the country R580-billion per annum, and growing. As a percentage of GDP, it’s too high. And one has to address that.”

How, though? A voluntary retrenchment offer has been talked about — but it wouldn’t net enough savings, and the public sector unions will not countenance forced retrenchments.

The answer, of course, is the dream of a true social compact between labour, the state and business — one in which pivotal trade-offs can be made and virtuous circles can be triggered.

“On the one hand, you want to reach out to labour as partners of industry. Why shouldn’t they be on boards of companies, as in Germany? Isn’t employee share ownership more important than enriching unrelated BEE [black economic empowerment] companies?

“But at the same time, you also want labour to be productive and efficient, and partners in managing the public sector and getting more bang for the state’s buck. You want them to agree to terms that would allow more investment in high labour-absorbing industries in export processing zones.”

For Coleman, every player has to give ground. “Are workers and businesses prepared to take short-term sacrifices for longer-term gain? The government needs to become more efficient.

“All players need to facilitate more transformation. If there is pain on all sides, and gain on all sides, and the whole is greater than the sum of the parts, then South Africa has a winning social compact.”

And if anyone can swing such a deal, Ramaphosa can, Coleman believes.

“He is highly strategic — but also very tough and able to face people down in the negotiation moment. He also knows when to look up and say we need to get a deal done — to get the best out of it without losing the deal. He’s prepared to push pretty hard.”

Crunch time: Coleman with the international mediation team led by Henry Kissinger and Lord Carrington in March 1994. Coleman co-ordinated talks to reach agreement on the basis for the ANC, Inkatha Freedom Party and National Party to all participate in the April elections

But first, Ramaphosa has to consolidate his political base. “After the elections, assuming that it goes well, he should then be in a position to move forward. The process of the recall of Jacob Zuma felt interminable, but we got there. This mining and land debate feels interminable, but I think we’ll get through it.”

Coleman comes from a family of activists. His father, Max, was a conservative businessperson — until 1981, when his son Keith was locked up without trial for months, in the cell next to that of Neil Aggett, the doctor and unionist who died in detention. “My father stood outside John Vorster Square every day with a placard saying: ‘My son, Keith, in detention x number of days. Free all detainees now!’”

The Colemans co-founded the Detainees Parents’ Support Committee. Max eventually sold his business to become an ANC MP and then human rights commissioner. Coleman’s mother, Audrey, was a Black Sash activist and later ANC provincial MP in Gauteng. “I am deeply proud of their contributions,” he says.

Coleman’s brother, Neil, is a former Cosatu unionist, who has recently launched a left-leaning research centre, the Institute for Economic Justice. They have a healthy ideological contest, says Coleman. “The reality is we have very similar ways of thinking, if not what we think. We are very close.”

Colin studied architecture at the University of the Witwatersrand, but his Nusas experience inspired him to form the nonpartisan CBM, which represented progressive business in facilitating the early talks between the state and the ANC.

“After Codesa was completed, I was put on the ANC election list in 1994 but I had to withdraw my name as I was involved in a non-partisan movement. After the elections, I decided to go into the economy, as I thought it would be the most important site of change, and banking seemed to be the best way to be exposed to all sectors.”

After 18 years at Goldman Sachs, with a catalogue of mega-deals behind him, Coleman is a doyen of Jo’burg’s money and power elites. He and his partner Nerina Labuschagnehost lavish, celebrity-haunted parties. “My job is originating and developing relationships, professional and social. My parties at home are a way to connect those people and bring them together.”

If he could go back in time to 1994, who would he collar at a cocktail party? “I would want to speak to the business community back then about getting behind the [Thabo] Mbeki project more forcefully. There was a lot of petty criticism from the business community and, in retrospect, I think they can all see they should have embraced the transformation programme and the democratisation agenda that Mbeki was leading. It was in the interests of a market economy — and business was largely absent from the debate.”

But the ANC has screwed up too, he says. “The one thing the democratic movement clearly got wrong was thinking that the Polokwane moment was a democratic silent coup, when in fact it was effectively the ceding of the sovereignty of the state to a corruption project.

“And that was a historic mistake. It cost us 10 years. Now, under Cyril’s leadership, the ANC has one last chance.”