On the far side of the path that Mars traces around the sun, but before the orbit of the gas giant Jupiter, we find our next goose: the asteroid belt. (German Aerospace Centre)

The story of the space elevator is one you already know. Here is the executive summary: Jack, beanstalk, castle, giant, oh look a magic goose that lays golden eggs. Burglary, suspicious death of property owner in nasty fall, happily ever after. Done.

But you know what else was done? Only the whole damn economy!

In the 15th century Spain threw Europe into financial turmoil for 150 years by discovering a magic goose of its own: the gold and silver of the Americas — as well as a whole new continent of indigenous people to exploit at musket-point.

Back home, too few people suddenly had too much money and bought too many things. So things ran out, inflation soared, and existing wealth was devalued. Mass migration, urbanisation and food shortages meant that destitution became nearly absolute. Everything got very, very messy.

It took centuries for the Old World to recover. The New World was never the same again.

And that’s what happens when someone finds a golden goose.

On the far side of the path that Mars traces around the sun, but before the orbit of the gas giant Jupiter, we find our next goose: the asteroid belt.

As much as 10% of the tumbling space rocks there are made up of elements worth a pretty penny if you can get them back to Earth. But before you mine in space you have to get to space. And getting there is bloody expensive.

Lockheed Martin and Boeing used to charge upwards of $20 000 a kilogram to launch cargo into orbit on their Atlas V rocket. They’ve had to cut that to $13 000 since the arrival of SpaceX, which itself can charge as little as $2 200 a kilo on its Heavy Falcon rocket.

SpaceX is run by the erratic capitalist and spelunking aspersion-caster Elon Musk, who wants to bring the price down even further to around $80 a kg on the next model in the Falcon line. The Big Falcon rocket (go on, say it out loud), is meant to be one day take colonists to Mars. Which coincidentally is right next to the asteroid belt.

Japan, meanwhile, has been practising landing on asteroids. Its Hayabusa2 probe has been in the headlines for visiting the asteroid Ryugu. According to Planetary Resources — a real asteroid-valuation company that actually exists — Ryugu’s potential mineral yield is worth $82.76-billion.

But even if an asteroid was successfully mined, it would still be difficult to move its minerals to market. You could just lob it over the side of the space station and hope it lands somewhere soft, but that’s hardly ideal. Which is why big players are actively investing in space elevator tech.

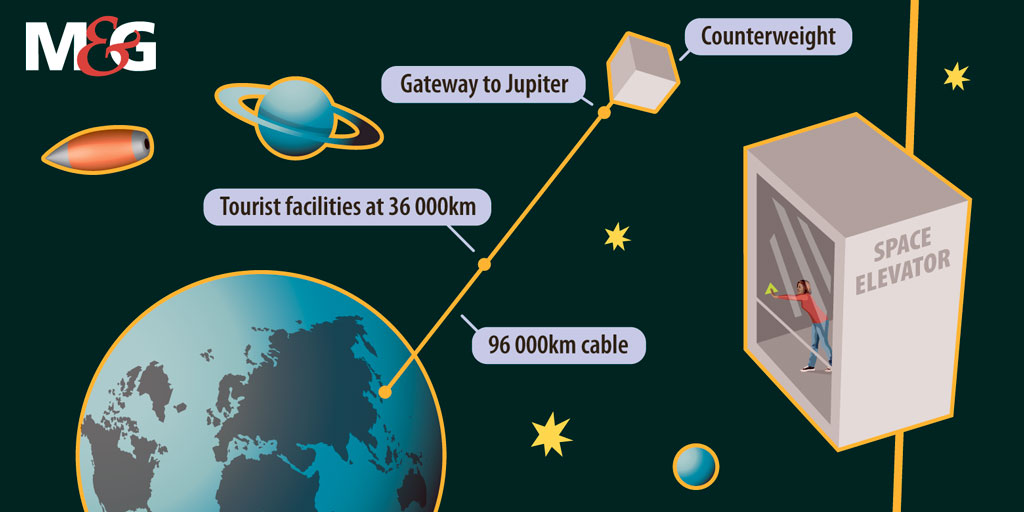

Here’s how a space elevator works. Step 1: Tether a space station to Earth with a slender but sturdy ribbon using as-yet-uninvented materials. Step 2: Make an elevator that can crawl up and down the ribbon. Step 3: Send stuff up and down more cheaply than by using rockets. Step 4: Profit.

According to the president of the International Space Elevator Consortium in California, Peter Swan, an elevator could bring the cost of shuttling cargo and passengers between Earth and orbit to less than $12 a kilogram a trip. And that’s when things get interesting. And pre-apocalyptic.

The United States’ Nasa has been actively conducting feasibility studies since the late 1990s and, in 2012, the Obayashi Corporation in Tokyo announced plans to build a space elevator by 2050, projecting construction costs of approximately $90-billion.

Not to be outdone, the China Aerospace Science and Technology Corporation in November last year laid out plans to build a space elevator by 2045.

A month ago, researchers from Shizuoka University got Japan into pole position once more, saying they were testing the mechanics of tether-crawling in an experiment launched from the International Space Station.

And later this year the US military — which you’ll recall now has a Space Force — will join discussions about how to stop space junk from bashing into an elevator.

Whoever gets their elevator up and running first will be in prime position to exploit the resources of the asteroid belt. Others will follow, but so too will massive disruptions to the global economy as commodity prices plummet in a flooded market and expensive terrestrial mining operations find themselves outpriced and redundant. Economies will falter, nations will fail, and everything will get very, very messy.

And that’s what you risk when you build a beanstalk. If you go looking for a gold-laying goose, don’t be surprised when you discover it’s not magic at all. Just cooked.