Non-fiction: Tshifhiwa Matodzi and Andile Ramavhunga are lead characters in Terry Motaus report into the banks actions that have devastated its victims. Photo: Mduduzi Ndzingi/ Gallo Images/Sowetan

Justice demands that someone who recommends decisions about the fate of others should do so with a certain amount of emotional distance. But, from reading Terry Motau SC’s report, VBS Mutual Bank: The Great Bank Heist, you can see traces of lyrical indignation.

To take a leaf out of the report (by Motau in association with Werksmans Attorneys), the indignation is neither “gratuitous” nor self-aggrandising. But it has been enough to generate a certain enthusiasm from the public gallery, who mused over Motau’s turn of phrase and the moral undertow guiding his pen.

Terry Motau has been referred to as a latent fictioneer. Photo: Rosetta Msimango/City Press

The 140-page report, beginning with a reference to the 1978 Krugersdorp bank robbery, turned Motau into something of a public personality, with social media users deeming the report to be the work of a latent fiction writer. Motau’s way with words was perhaps a fitting reminder of the scale of the calamitous “pillaging” that took place at VBS between March 1 2015 and June 17 this year, when, according to the forensic accountants’ report, “the amount of R1.8-billion was gratuitously received from VBS by some 53 persons of interest, both natural and juristic”. The degree of the rot led Motau to conclude that “there is no prospect of saving VBS”.

As the story dominated the news, one got the sense that, besides the alleged culprits’ guilt, it was Motau’s diction that further incensed them. He portrays Tshifhiwa Matodzi “as firmly at the helm” of what he characterises as a single criminal enterprise, in which VBS and its majority shareholder, Vele Investments, netted nearly R940-million. Matodzi is said to have pocketed about R326-million.

In the introduction to the characters involved, “the dramatis personae”, Motau unleashes a combination of adverbs, adjectives and nouns to describe their actions. Andile Ramavhunga, the executive director and chief executive of VBS, who is said to have taken nearly R29-million, “steadfastly denied” that he was involved in anything unlawful, despite the alleged evidence to the contrary.

Paul Magula, a nonexecutive director of VBS, nominated by his previous employer, the Public Investment Corporation, which holds 26% of VBS’s issued shares, put up “strenuous denials” about being a conduit for R7.6-million destined for two companies that had nominated him. Before “eventually” confessing, one can almost see him shifting in his chair, palms sweaty from the strain of denial.

The word “strenuous”, when appended to denial, appears several times in Motau’s gallery of rogues. People have steep prices for their complicity and the “looting proceeds with alacrity”, especially after the departure of Yolanda Deale, who, as Motau’s report informs us, was an accountant in the employ of VBS until February last year.

If not brimming with an internal sense of rhythm, Motau’s phrases hint at alliteration.

Takalani Veronica Mmbi, Matodzi’s “faithful” assistant, who set up and operated companies apparently used to launder the proceeds from VBS, was “remunerated richly for her efforts”, and “spirited away documentary records” when VBS was placed under curatorship.

In the game of cat and mouse that accompanied the curatorship, Matodzi “pandered the preposterous tale” that “Vele had intended to borrow R1.5-billion from VBS but, inadvertently, had neglected to sign the necessary documentation evidencing the grant of such a loan”. It is prose that matches the theatricality of the entire fiasco, so brazen in its execution and oblivious to accountability.

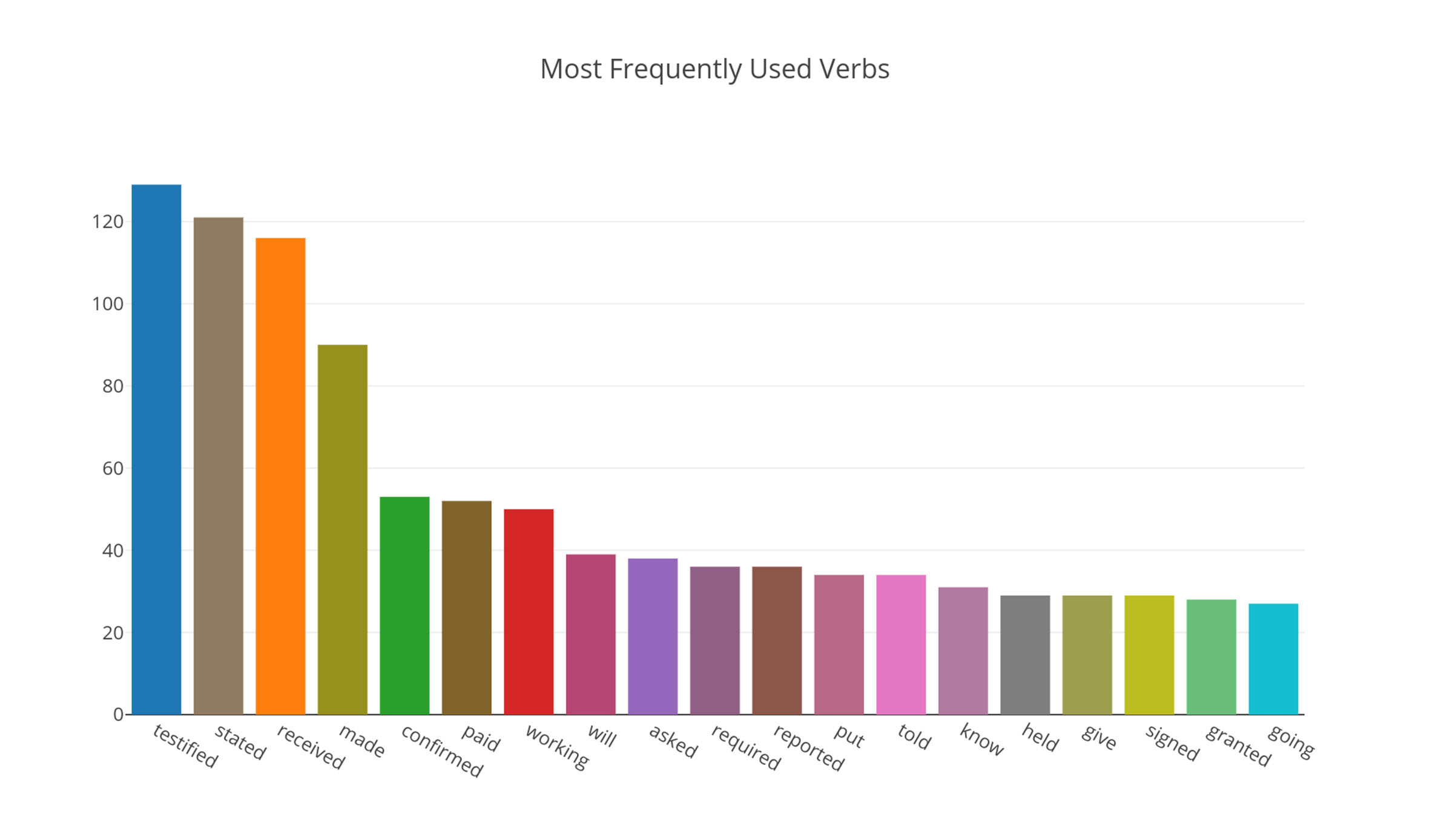

The most frequently used verbs in Terry Motau’s report

If Motau is a “latent fictioneer”, as he was referred to in a Twitter conversation between writers Percy Zvomuya and Sisonke Msimang, it is because he spent five months down a rabbit hole in which fiction seized the day.

Restrained as he must be as an impartial investigator, Motau, as a responsible citizen, invariably joins a chorus of public incredulity. “It does feel like fiction,” poet Khulile Nxumalo wrote on WhatsApp. “Delusions of grandeur! Manic gulping of materialism, bad suits with pink shirts … Old women sleeping outside the building of a collapsing bank. Is money a paper or a digit?”

Indeed, the report bulges with so many digits you would think it was an optical illusion. Our aversion to decimals doesn’t help either.

Although the plunder of VBS is avarice pushed beyond the point of satire, a parallel political circus makes fact and fiction indistinguishable. Motau’s report, meanwhile, slows its pace as it drills down to the scale of municipal co-option and parastatal manipulation. Dry, economical language abounds, with the odd lyrical flourish that characterises the earlier pages. There are, thankfully, moments of illuminating and simultaneously absurdist dialogue.

In between the VBS henchmen’s insistence on referring to the municipal deposits as “investments”, there is Kabelo Matsepe (the alleged fixer between VBS and the municipalities) and Ramavhunga’s conversation about “the guy”, a Passenger Rail Agency of South Africa bigwig, whose palm allegedly had to be greased to secure a R1-billion deposit for VBS. In snippets of the conversation Matsepe says: “I think this Prasa is important more especially that we can get the funds by Wednesday … The guy is going to give us money … He was just uncomfortable about many people being involved … He has R13-billion investments with all the banks, so he will give us 1-billion and if we do it right he gives us another two after a month.” Ramavhunga responds: “Let him give us the money, then we will be sorted for the rest of the year.”

Matsepe later updated the exchange, when they discussed the possibility of a 24-month fixed deposit, which would help to push the bank’s ratings, allowing them to pursue a similar strategy with “Transnet and SAA”, in Ramavhunga’s words.

Although this is salacious enough, it is par for the course in the context of the report’s plot. The clincher, though, is Ramavhunga’s denial when questioned by investigators.

“Ross Hutton: ‘Mr Ramavhunga, I will ask you one final time, who is ‘the guy’?’

“Ramavhunga: ‘I don’t know, chair. I have said that before.’

“Hutton: ‘Well, nowhere here do you ask him, who is the guy? Surely it would have been immensely useful to know who the guy is who is going to bring all this money into VBS, and resolve all of your liquidity problems for the next year …’

“Ramavhunga: ‘If I was interested in the transaction, yes, but I’m simply saying I was not interested in this transaction.’ ”

Motau couldn’t have plotted a more convincing story.

On eNCA, asked why he believed VBS is beyond redemption, contrary to the narrative the Economic Freedom “we are not our brothers’ keepers” Fighters, Motau responded: “It cannot be that we talk about the colour of the bank and yet we don’t talk about the victims, who also happen to be black. And for me, that’s the unfortunate narrative that is being put out there … For me that should be the narrative rather than what people are talking about.”

If Motau’s recommendations that the attorneys and accountants who are so ubiquitous in the VBS “pillaging” should be stripped of their rights to practise seem harsh, perhaps see it as an act of love for those they fleeced. As a people it is hard to get over holding ourselves to a higher standard. Colour or no colour, you would think the Red Berets would know better.