Through its branches, TAC was able to mobilise large-scale support for campaigns like that which saw 15 000 people march to Parliment to demand an HIV treatment plan. Today, the country issues one such plan every five years. (Supplied)

Ten people, three banners, one folding table and just a handful of petitions — the fight to save the lives of millions of HIV-positive people began with the trappings of no more than your average mall fundraising stand on a December day at the foot of Cape Town’s St George’s Cathedral.

“The National Association of People Living with Aids has initiated the Treatment Action Campaign (TAC) to draw attention to the unnecessary suffering and Aids-related deaths of thousands of people in Africa,” said a statement released 20 years ago announcing the TAC’s formation.

The organisation spread from that small demonstration seeping into homes, streets, community halls and even doctors’ offices around South Africa as activists and experts banded together to fight Aids denialism and quackery. The group took the government to court to compel it to provide treatment to protect children born to HIV-positive mothers and then, finally, to everyone living with HIV.

Then, it taught people living with HIV to understand their drugs, how they worked and the importance of taking them every day.

But it didn’t stop there. The TAC used its iconic HIV-positive t-shirts to start conversations in communities about HIV stigma. Once donned by former President Nelson Mandela, the distinctive shirts have travelled the world worn by everyone from United Nations diplomats to Zambian activists as they fought their own battles for treatment.

The TAC became a “sort of the spiritual leader of [HIV activism]”, former UN Special Envoy for Aids in Africa Stephen Lewis once said. Lewis went on to cofound the organisation Aids-free World.

Today, in fact, we may need the TAC more than ever, he warns in a recent video message to the group.

This week, as the TAC turns 20, we look back at two decades of HIV activism in 11 iconic posters.

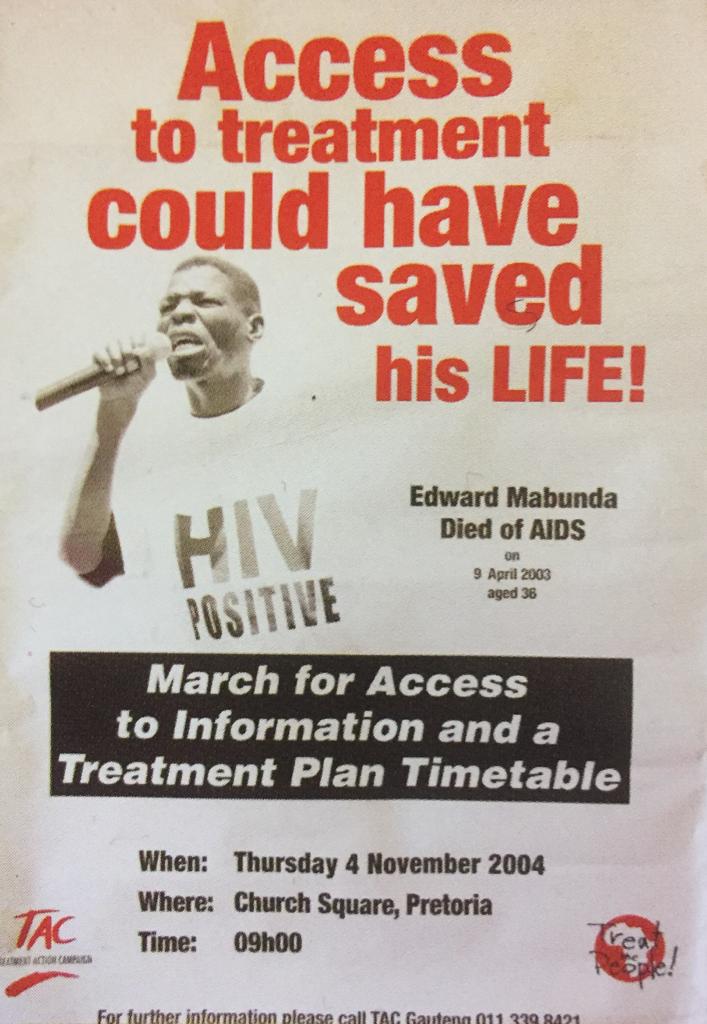

1. ‘We want ordinary people in South Africa to have antiretrovirals (ARVs). I am urging people all over the world to show solidarity.”

These were Edward Mabunda’s last recorded words. He died at the age of 36, one of more than 330 000 South Africans who lost their lives between 2000 and 2005 because of President Thabo Mbeki’s refusal to provide HIV treatment, a 2008 study in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiencies estimated.

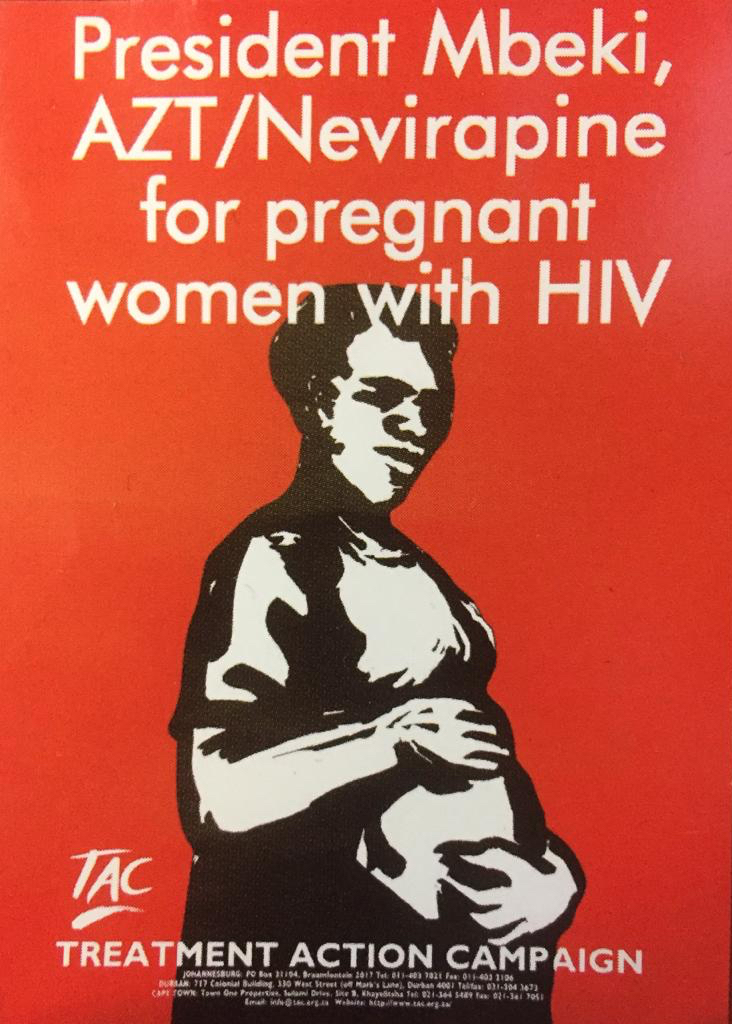

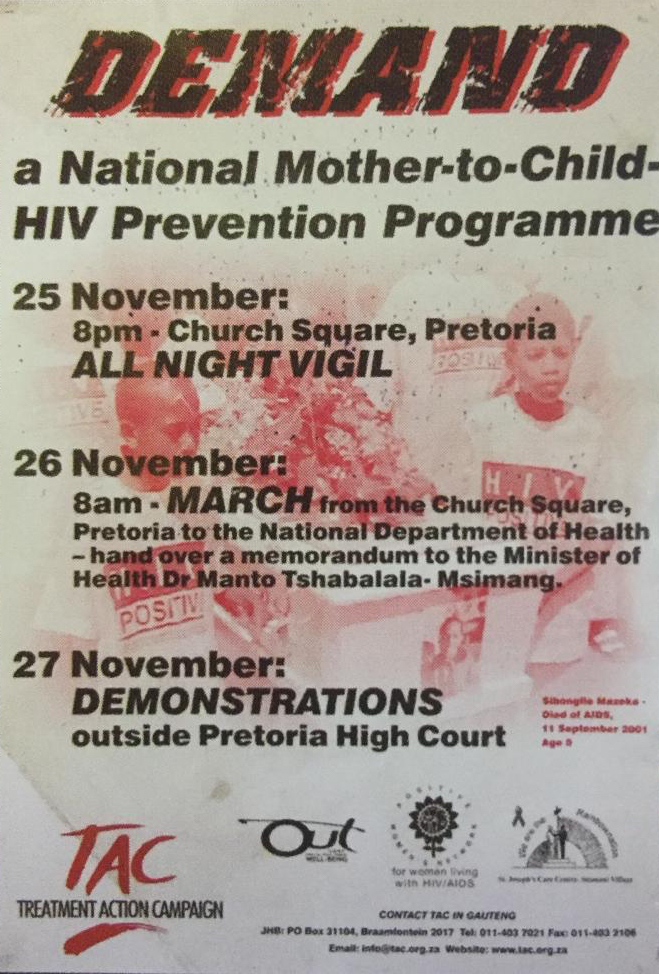

2. Without treatment, about a third of babies born to HIV-positive mothers will contract the virus either before, during or after birth, a 1996 South African study published in the Pediatric Infectious Diseases Journal found.

But in 1994, researchers found the first evidence that a combination of two antiretrovirals, Zidovudine (AZT) and nevirapine given to newborn babies could reduce the risk. The TAC quickly took up the cause.

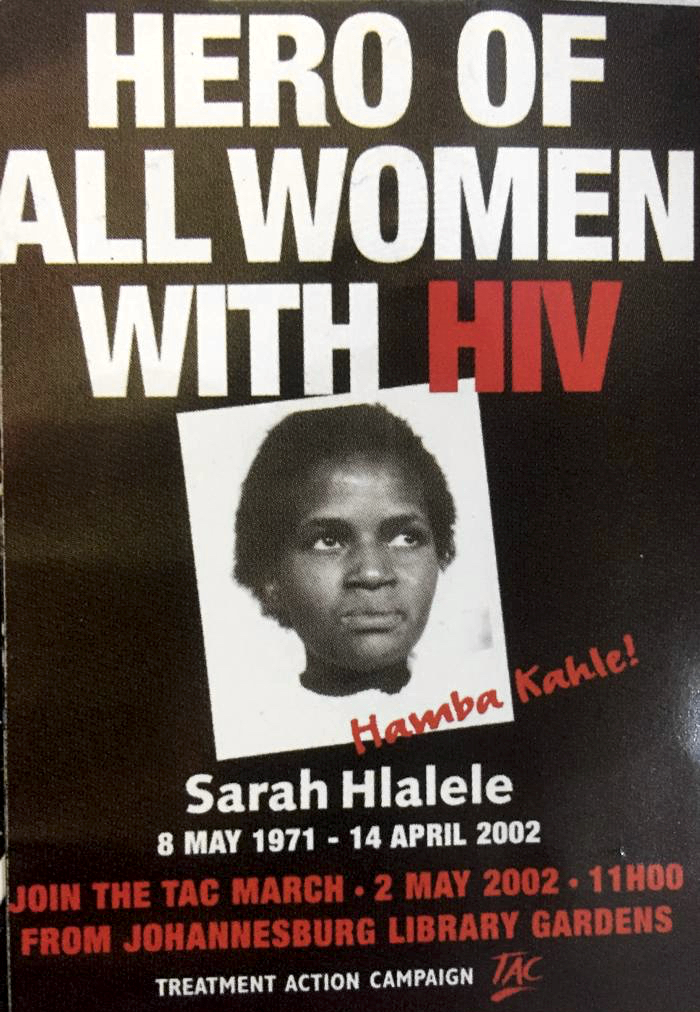

3. Sarah Hlalele became the plaintiff in the TAC’s 2002 Constitutional Court case that ultimately compels the state to begin providing prevention of mother-to-child HIV transmission (PMTCT) services. The judgement comes too late for Hlalele’s son Kgotso. Read more about her story here.

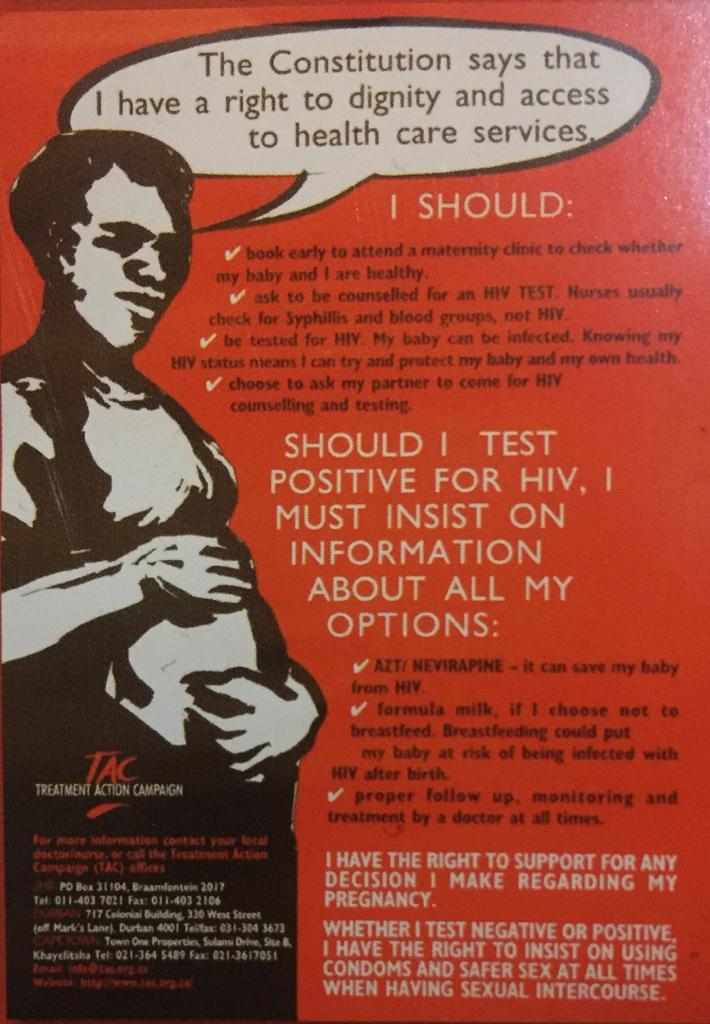

4. After the TAC won the Constitutional Court victory, it taught mothers about their right to treatment and how to use it.

Many people thought women wouldn’t test without treatment being available for themselves but being able to help their babies was enough to convince them.

5. Today, less than 2% of babies born to HIV-positive mothers contract the virus from their mothers as of six weeks after birth, according to results announced at the 2016 International Aids Conference.

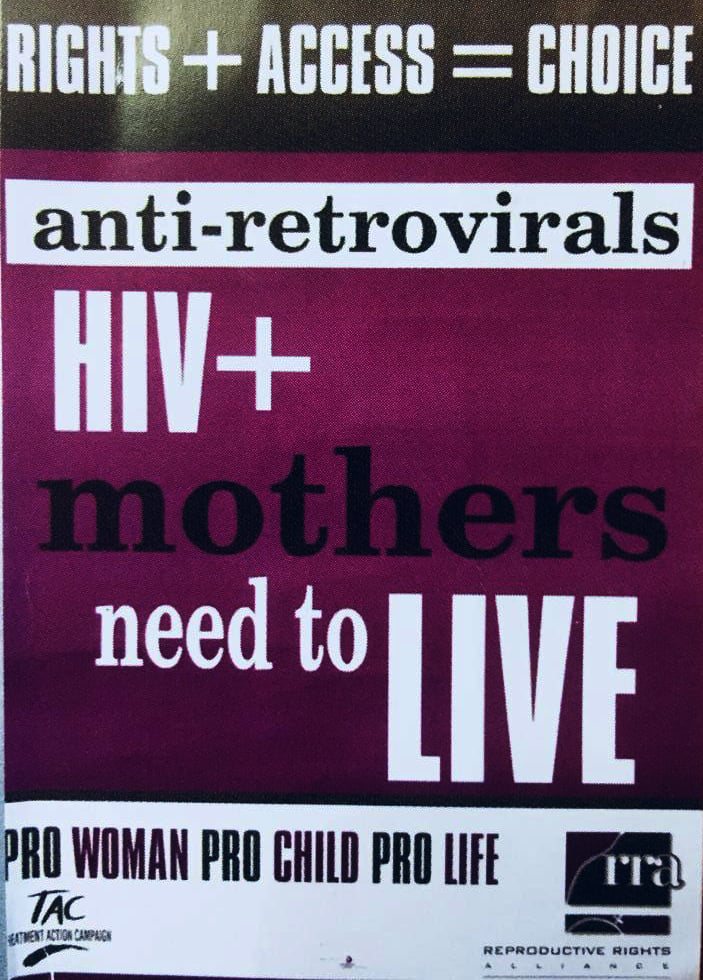

6. Mothers could now protect their babies, but without treatment, they wouldn’t live long enough to see them grow.

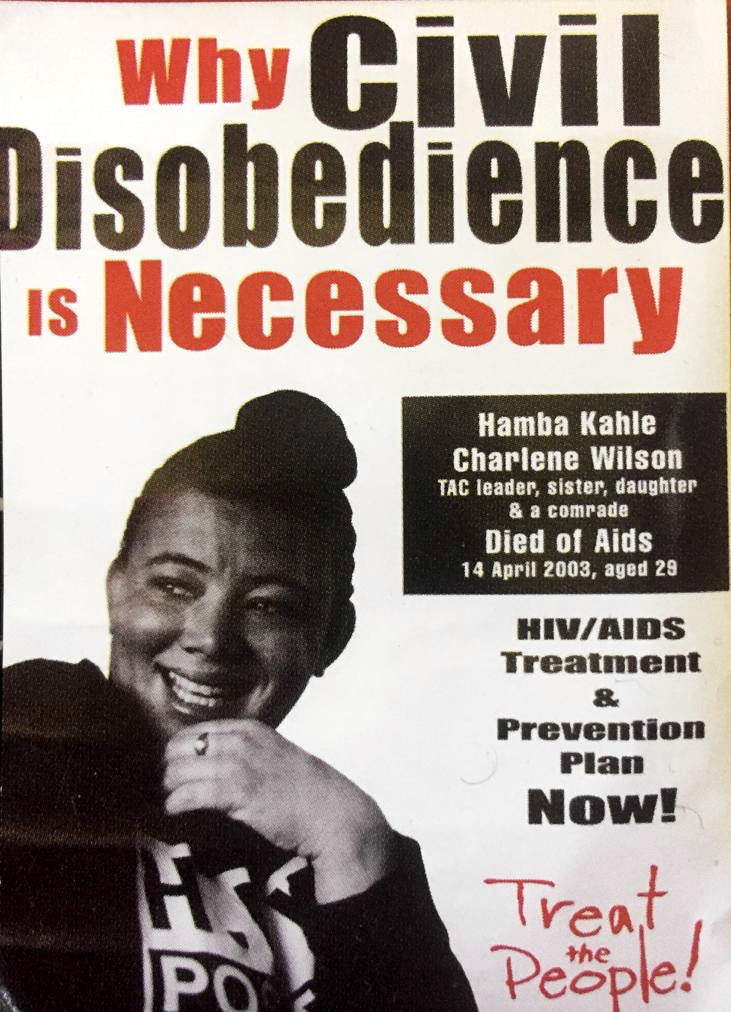

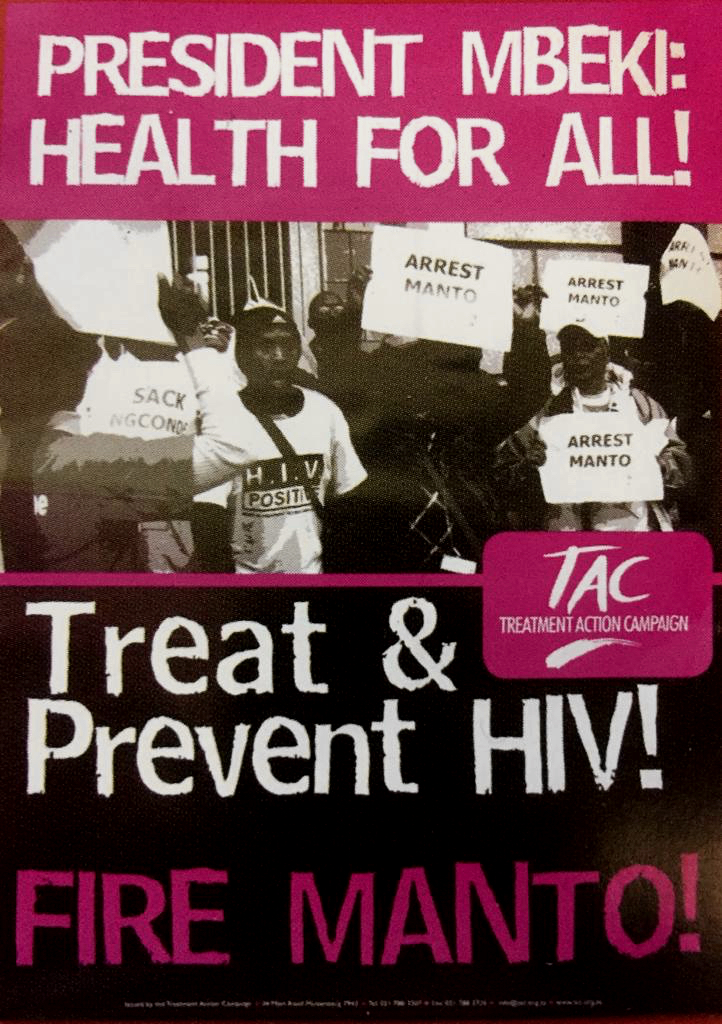

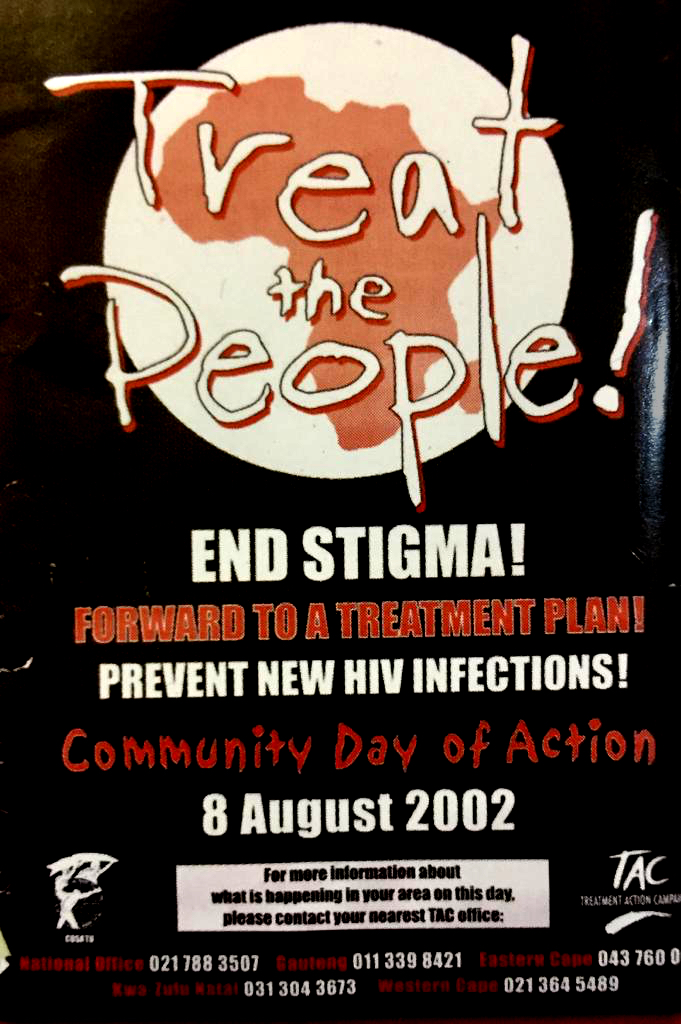

7. And as more people died, the TAC continued the pressure — conducting die-ins and marches to call for treatment.

8. It works, and in 2004, South Africa slowly begins rolling out HIV treatment in the public sector.

9. The TAC also battles stigma and quackery, educating people living with HIV about the science behind the virus and medication. Doctors taught activists, and activists taught each other, communities and journalists.

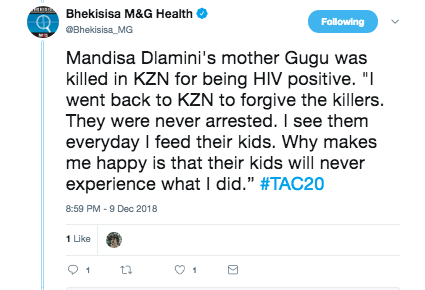

Unfortunately, stigma still leads to the murder of several TAC activists, including Gugu Dlamini and Lorna Mlofana who were killed for being HIV positive.

This is how Dlamini’s daughter, Mandisa, remembers the day she lost her mother:

“I didn’t know what Aids was, but my mother went on national TV and told her story. Her friend came over a few days later and said, ‘Let’s go to a party.’ “When they were [at the party], people said a guy came in and pushed [my mother] outside and asked her, ‘What are you doing here? You want to kill us all?’

“Then they [members of the community] started beating her with anything they could find. When they were done, they pushed her down a cliff and they told the neighbour, who was also [HIV] infected and a friend of my mother’s, ‘Go and tell them to come and fetch their dog, we are done with it.’ I had to go there with [my mother’s] boyfriend to fetch her. We went and looked for help from the neighbours but they wouldn’t help take her to hospital because they thought their cars would also be infected and they would die of Aids”.

Mandisa eventually returned to KwaMashu, KwaZulu-Natal where her mother was murdered and now runs the Gugu Dlamini Foundation.

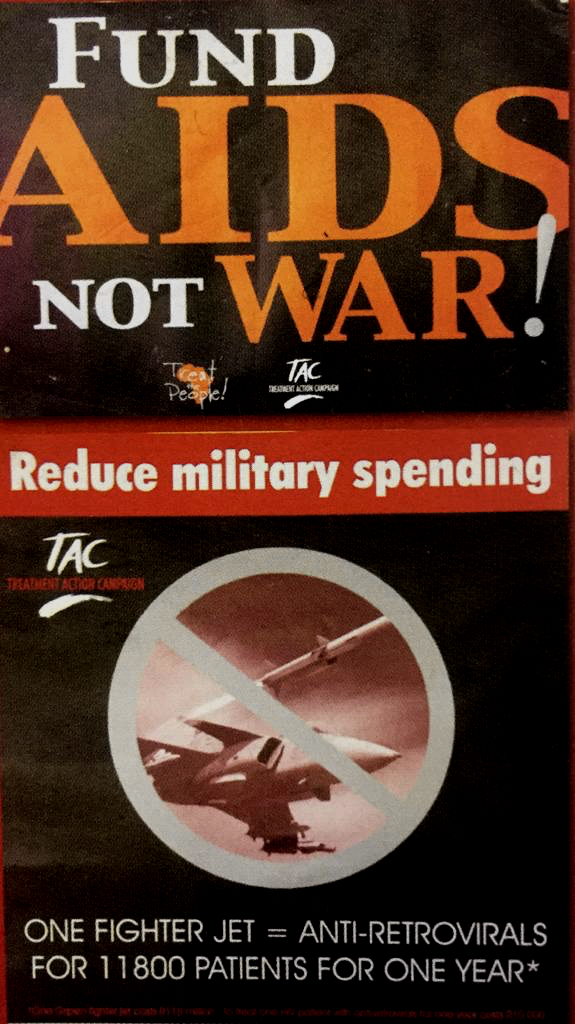

10. But when medicine came, it didn’t come cheap. In 2002, monthly ARV treatment cost more than R2 000 per month.

11. Both the TAC and its US counterpart Act Up’s work to educate people with HIV on intellectual property law helped both groups take on Big Pharma to fight for cheaper drugs.

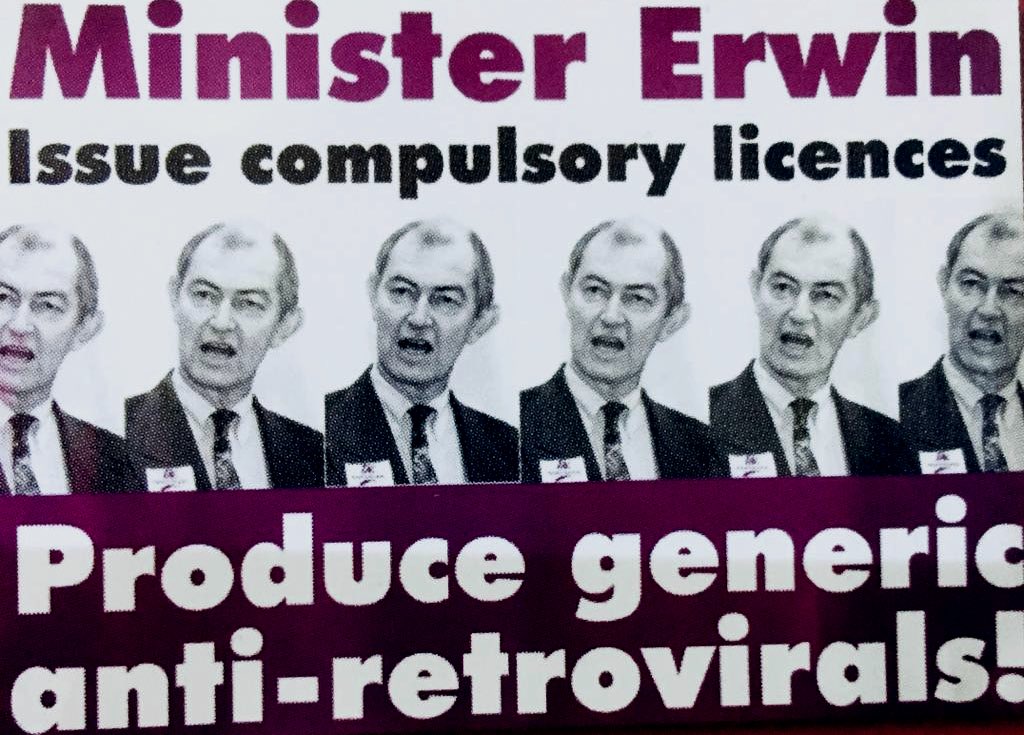

In South Africa, the TAC lobbied for former trade and industry minister Alec Erwin to issue compulsory licenses on certain HIV medications. This kind of arrangement would allow other companies to produce a product without a patent because of the public health emergency.

Today, the South African government pays just a fraction of what it did for HIV treatment a decade ago and runs the world’s largest ARV programme.