Prison life: Zimbabwes Chikurubi Maximum Security prison, from which seasoned criminal Stephen Chidhumo, who was a student of the martial arts, escaped, only to perpetuate more crimes. (Jekesai Njikizana/ AFP)

A recent review of Richard Wrangham’s The Goodness Paradox: The Strange Relationship between Virtue and Violence asks: “Did capital punishment create morality?” It’s an ages-old polemic that continues to occupy the minds of many and, in Zimbabwe, there are renewed calls — especially after the fall of Robert Mugabe — for the abolition of the death penalty.

Only weeks before his November 2017 ouster, Mugabe expressed a yearning for executions because of what he saw as in increase in callous murders across the country. This makes the aforementioned question even more compelling.

One of the leading lights in the campaign against the death penalty is none other than the man who ousted Mugabe, President Emmerson Mnangagwa.

According to sometimes apocryphal lore, a young Mnangagwa was charged with treason back in 1965 and sentenced to hang. But, as fate would have it, he escaped the gallows on account of his youthfulness. According to popular legend, as others suspicious of many a hagiographic retelling of the Second Chimurenga narrative claim, some other factors weighed in to have his sentence “reduced” to 10 years.

One of Zimbabwe’s most enduring post-independence death row biographies is that of Stephen Chidhumo, one of the country’s last executed felons.

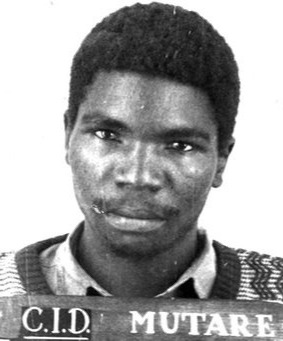

Notorious celebrities: Stephen Chidhumo has become so celebrated in Zimbabwe that children use his name as a nickname in games and sport. (Supplied)

By all accounts, Chidhumo was no ordinary guy. Newspapers lionised him. The public was awed at the mention of his name. Public transport vehicles across the country were christened Chidhumo, clumsy stenciling in gaudy colours proclaiming a sort of cultic devotion to what could well be a whole community’s favourite son. Young boys dribbling plastic soccer balls in dusty township streets called themselves Chidhumo, where others would have called themselves Pele or Maradona.

But there was nothing to romanticise about him. Chidhumo was a robber, rapist and murderer.

A police mugshot shows him with a big matted afro, staring blankly straight into the camera.

Notorious celebrities: Stephen Chidhumo has become so celebrated in Zimbabwe that children use his name as a nickname in games and sport. (Supplied)

He became an iconoclast of celebrity culture as we know it, regularly referred to as Zimbabwe’s most notorious criminal ever since his name first appeared in print in about 1991.

As he spooked the country’s streets, his name, if not met with fear and loathing, was met with admiration usually reserved for cinema’s bad guys. Indeed, his life imitated art. Between 1991 and 2002, when he was executed, he dominated the country’s most-wanted charts, eluding and taunting the authorities with several daring jailbreaks.

He led a gallery of rogues; some of those who rode his audacious crime wave created their own “dangerous crew” that pillaged, raped and murdered. Theirs was a gang of young men that did not follow the lore of idle urban gangsters whose signature activity was to harass and bully young women and then go home to sleep soundly without having attracted the wrath of the law. The fact that Chidhumo had acolytes attests to something enigmatic, something disturbingly charismatic about him.

Here in Zimbabwe, where criminal enterprise is rewarded with lice-infested prison blankets, lavatories that do not flush, meals that elsewhere are not even reserved for mangy canines, sodomy and brutal, underpaid and overworked prison officers, it is hard for anyone to understand why being a Chidhumo associate would be considered an attractive proposition.

According to some accounts gleaned from police archives, court records and newspaper reports, Chidhumo and his gang would retreat to their rural homes to cool off after committing serious crimes. They would make no effort to go underground, as it were, with one rural businessman telling a newspaper that he regularly saw Chidhumo playing pool during the time he was said to be on the run. What cheek!

Chidhumo began his criminal enterprise as an OMG (one man gang) and was first arrested in 1991, aged just 18, for car theft. He was released after spending four years in prison, according to Zimbabwe Republic Police (ZRP) records.

It was clear, however, that despite his conviction in 1991, Chidhumo decided that crime did pay after all, and that the elders who earlier in his life had told him to stick to his books for a better and more civilised adult life did not know what they were talking about.

His was a case that ought to have had penologists pondering whether prisons, at least Zimbabwean prisons, were serving their purpose of rehabilitating offenders and adequately preparing them for full re-integration as respectable members of society. This is because his release in 1994, at the age of 21, saw him graduate to what he must have considered a more lucrative, adrenaline-fuelled smorgasbord of crimes that ranged from armed robbery to rape and attempted murder.

For Zimbabwe, and perhaps the rest of the world, the 1990s were a time when newspapers made healthy profits and folk had no problem buying a government-controlled newspaper.

His sister would later tell a newspaper reporter that Chidhumo grew up a God-fearing young man, a character witness account that was corroborated by village elders who described him as a quiet, unassuming lad. But, as adulthood beckoned, his innocence and lack of parental guidance coalesced into something ominous.

No professional psychological profile exists of Chidhumo, yet his exploits could easily place him in the same league as notorious psychopaths.

According to Walter Mangezi, a psychiatrist at the University of Zimbabwe, there were a lot of factors that could drive someone like Chidhumo to a life of lawlessness.

“Human behaviour is a combination of nurture and nature. A trauma in childhood and growing [up] in an environment that socialises crime, for example, lack of boundaries and values and a parent figure to enforce these can result in crime,” he said.

“One can also be born with genes that predispose [one] to

criminal behaviour, for example anti-social personality disorder,” he continued.

Chidhumo’s father was reportedly a former police officer and Chidhumo practised karate. These factors would ordinarily point to a disciplined background. How then did he fall off the tracks so spectacularly?

According to the ZRP, when Chidumo was released in 1994, he began a new life, living with relatives in Bulawayo, the country’s second-largest city. It is safe to bet that he imagined he was anonymous in his new domicile and that he could continue with his criminal ways “unnoticed”. He was, however, soon arrested, only to escape from police custody in Masvingo, home to the Great Zimbabwe ruins.

By that time, it was clear that Chidhumo had long discarded any ideas of following the civilised ways of his ex-cop-turned-businessman dad. In August 1997, he escaped from Chikurubi Maximum Security Prison.

Two of his accomplices were to meet violent deaths, shot by police less than 24 hours after their escape from Chikurubi.

The ZRP reported: “Chidhumo made history and in a movie-like-style escaped from Chikurubi Maximum Prison with three others — ex-policeman Pedzisai Musariri, ex-soldier Elias Chauke and Mariko Ngulube. Musariri was shot dead, Chauke was recaptured and Ngulube died from serious wounds sustained during the escape. Chidhumo managed to escape unscathed.”

For many ordinary Zimbabweans Chidhumo was still the anti-hero they rooted for, despite the trail of gore he left behind. Police pointed out that Chidhumo was a student of the martial arts and that he practised karate, now a horrible detail, considering he was a rapist and was certain to have used those skills to subdue his victims. He was, after all, from an era during which the iconic martial artist Bruce Lee was an idol to many young men who could be seen practising karate kicks on each other’s heads soon after the credits started rolling on a Kung Fu flick at the local municipality hall.

Chidhumo made it all the way to Beira in neighbouring Mozambique and a bounty of 60 000 Zimbabwean dollars (a lot of bread back then) was quickly put on his head.

His freedom lasted a mere 29 days, and records show police acted on a tip-off from members of the public. It is unclear whether the tipster got the windfall.

His recapture reads like something straight out of an action movie. He would later explain in court that he had planned to assume a new identity when he went into hiding in Mozambique. And, under a new identity, he would continue to rape and plunder as he had done previously after his first and second prison breaks.

Aged 29 when he was executed in 2002, Chidhumo belonged to the generation that had witnessed the cultural influences and vestiges of the colonial era when local bioscopes showed all kinds of fare that included “shoot ’em up” flicks from Clint Eastwood, Lee van Cliff, Charles Bronson and other trigger-happy celluloid heroes and villains. He could well have been a psychoanalyst’s dream, determining whether television or movie violence had made him do it.

The police heaved their own collective sigh of relief when he was captured, well aware that members of the public were blaming police incompetence for Chidhumo’s continuing reign of terror.

In commenting that his arrest returned sanity to the country and restored the public’s confidence in the police, the ZRP virtually admitted that the public had lost confidence in them.

How did he manage to escape unscathed? In court the daring escape was laid out.

Chidhumo was arrested with his long-time accomplice, Edgar Masendeke. Jonathan Samkange, today a Zanu-PF legislator who is considered one of the country’s finest legal brains, was Masendeke’s pro deo lawyer, and he argued that Chidhumo had been persuaded by Musariri to take part in the violent escape that left one prison officer dead (shot by Musariri).

Stephen Chidhumo’s cohort, Edgar Masendeke has also achieved cult status in Zimbabwe, turning up in songs that celebrate his Houdini-like antics and cheeky bravado. (Supplied)

The legal counsel said the escape could only have been possible with the connivance of prison guards, with Chidhumo claiming in court that he had seen Musariri being given marijuana by a prison officer, which was then smoked by the escapees for courage.

Chidhumo’s lawyer told the court his client was convinced the escape would not involve any violence and his wish for a nonviolent escape was demonstrated by “his move to save a prison officer who was almost suffocated by Ngulube.

“Escapes from prison have been made before without the taking of lives,” Chidhumo’s legal counsel argued before the court.

This was given in defence despite Chidhumo’s own account of using a prison officer as a human shield during the shoot-out that killed another officer, to make good on his escape. Chidhumo told the court from his hospital bed that he had disarmed a guard then handed the gun to Musariri “who could use it properly”.

He claimed that during the escape, a spooked prison guard threw a gun at him. He would later use this same gun to rob a store, he said, in order to obtain money for his long walk to Mozambique, over 212km from Harare.

The Zimbabwean authorities enlisted the services of Mozambican police to find him.

But he did not go down without a fight. On October 15 1997, the police swooped on his Beira hideout, where he tried to attack them with a shovel, according to official accounts. He was, however, immediately immobilised, shot in the hip and thigh and brought back to Harare in an open police truck.

A few days later, a full court was held in his hospital ward. He was bedridden. It was at this point that he converted to the Catholic faith.

He assumed the baptism name Fidelis, after the Jesuit priest who baptised him, the same priest we would later learn was a long-time Mugabe confidante.

Chidhumo told the bedside court he had never considered Christianity before his capture. His was the classic case of being sorry because he had been caught not because he had done something wrong.

The court then asked him what he would have done had the prison officers not resisted. Would it have led to anyone dying during their escape?

“My Lord,” he replied, “we don’t deal with assumptions. My only intention was to escape.”

When he and Chauke appeared at the Harare high court in October 1998, security forces were in full force, armed with automatic assault rifles. Nothing was being left to chance.

It was the list of crimes that Chidhumo and his friend Masendeke committed that eventually led to the courts calling in the hangman.

Just in late 1996, Masendeke’s list of crimes are horrendous: he’d murdered a man but not robbed him; shot and wounded a detective who wanted to arrest him; shot and wounded a man and stolen his bicycle; robbed a store and fled with goods worth the equivalent of ZWD1 000 back then.

People were bound to come up with all sorts of theories and conspiracies in their attempts to understand such reckless derring-do.

Beliefs in the dark arts are rife in Zimbabwe and people have always turned to shamans and bogus medicine men for “strength” — be it for protection and promotion at their workplaces or for their general daily hustle. Criminals enlisted the services of these pseudo-magicians for protection, too, and their “bravery” could only be attributed to muthi.

The fact that the bandits and members of the public actually believed these things was of no consequence. What mattered was that the bandits did indeed seem to possess preternatural valour and managed to evade authority for such a long time. It only made sense then that all this senseless crime was because of the helping hand of the practitioners of black magic.

A later story would appear in a local daily about a Bulawayo traditional healer who was arrested after he was found with a stack of money believed by cops to be from a recent robbery. After a thorough interrogation (which we have always known here is an euphemism for thorough beating), the medicine man confessed that he had been given the money for cleansing so the criminals would not be caught. The shaman’s arrest should have alerted other aspiring robbers that such methods did not work, but instead it only worked to cast doubt on that particular shaman’s claims that he was the go-to guy, and that you enlisted his services at your own peril. For, indeed, medicine men continued to thrive across the country and one such supposedly all-powerful man was credited for Chidhumo’s long spree of blood and gore.

In November 1998, after a five-day trial, Chidhumo and Masendeke were sentenced to death. The two were hanged in 2002 for murder and for attempted murder of the prison guard, whom the pair insisted was shot by Musariri. Despite their denials of killing the officer, the courts said the pair was being charged under the principle of “acting in common purpose”.

The two were the last to be hanged in Zimbabwe, securing yet another dubious badge of honour for Chidhumo.

The duo still inspire younger generations.

In 2013, writer Tafara Shumba expressed his own frustration with criminal celebrity: “In February this year, I had to tell off my 10-year-old son after I heard him calling himself ‘Chidhumo’ in a mock athletics competition in the neighbourhood. I told him who Chidhumo was and eventually suggested to him the athletes he could idolise. When I went to his school … for the inter-house competitions, shockingly the teachers had nicknamed the houses Chidhumo, Masendeke and so on.”

In 2016 Kingbit, a young chanter of the Zimdancehall genre, paid his own homage to Chidhumo and Masendeke.

In the song, simply titled Chidhumo naMasendeke, Kingbit uses the two outlaws as a braggadocio trope, chanting that: People can look for me anywhere/They will never find me like Chidhumo and Masendeke.

In a 2012 bulletin citing Amnesty International, the Zimbabwean Human Rights nongovernmental organisation Forum said 78 people had been sent to the gallows since the country’s independence in 1980.

When Zimbabwe had an execution in 1995, it was the first time in seven years, according to officials, perhaps highlighting the lack of the society’s eagerness to carry out executions. After all, the country has been called “de facto abolitionist” because of the extended periods without execution, despite retaining it in its statutes.

In 2016 as then Justice Minister, President Mnagagwa appeared before the United Nations Human Rights Council and said Zimbabwe was not ready to repeal capital punishment as Zimbabwe had voted to have it in the constitution.

READ MORE: Free at last: The day Zimbabwe became independent

Zimbabwe currently has 101 inmates on death row. Post-Mugabe, calls have returned to permanently shut down the gallows, almost two decades too late for Chidhumo.