Belgian Femke Van den Driessche became the first cyclist to be charged with mechanical doping after one of her back-up bicycles was found to contain a motor.(Getty Images)

The International Chess Federation confirmed last week that it had suspended a grandmaster after he was “caught red-handed using his phone during a game”.

The suspect in question, 58-year-old Latvian-Czech called Igors Rausis, was investigated at a tournament in France after a cellphone was found in the toilet.

“I simply lost my mind yesterday,” he later told Chess.com. “I confirmed the fact of using my phone during the game by written [statement]. What could I say more? … At least what I committed yesterday is a good lesson, not for me — I played my last game of chess already.”

For the uninitiated: chess engines have grown infinitely in the years since Garry Kasparov’s seminal defeat to the hulking computer mass that was IBM’s Deep Blue in 1997. Today, a number of free cellphone apps can crush any human who has ever played the game.

Igors Rausis, was investigated at a chess tournament in France after a cellphone was found in the toilet.

Igors Rausis, was investigated at a chess tournament in France after a cellphone was found in the toilet.

Rausis is far from the first player who has sought to harness extra power. Grandmaster Gaioz Nigalidze became a high-profile perpetrator at the 2015 Dubai Open when his opponent complained about his frequent bathroom breaks. Organisers searched the stalls and, sure enough, found a phone hidden under some toilet paper.

The fact is that as long as there’s something to be gained by winning, players will look to force an advantage, one way or another. Whether it’s rushing to the loo like an exam-writing school kid or motorising your bicycle, there is no shortage of competitors who have disgraced themselves in the most amusing and creative of ways.

Take Geir Helgemo, world No 1 over at chess’s poorer cousin, bridge. The supposedly cultured game was rocked earlier this year when it was revealed the Norwegian had failed a drugs test.

The 49-year-old professional card player had been doping. Helgemo tested positive for synthetic testosterone, considered a performance-enhancing drug among athletes, and clomiphene, a fertility substance traditionally given to women who do not ovulate. Whether either of these has cognitive benefits (the extra lean muscle mass would not be needed in bridge, after all) is a topic of debate in the scientific community.

Whatever his motivation, the important part is that the International Olympic Committee recognises the World Bridge Federation (WBF), thus leaving its players beholden to the rules of the World Anti-Doping Agency. Helgemo was suspended for a year and stripped of all wins, medals and awards he had received from September 2018 onwards, the time of the testing period.

It’s hard to believe, that’s not as egregious as it gets in the bridge world. In 2014, two German doctors were discovered to be using coded coughs. By communicating in such a prearranged manner, Michael Elinescu and Entscho Wladow were found by the WBF to have committed “the gravest possible offence”. They were given a lifetime ban from playing with one another and suspended from competitions for 10 years. (For an idea of how this cough coup might have worked, search for “Charles Ingram” on YouTube and watch as he looks to the heavens and is rewarded with coded answers on Who Wants to be a Millionaire?)

Geir Helgemo tested positive for synthetic testosterone, considered a performance-enhancing drug among athletes, and clomiphene, a fertility substance traditionally given to women who do not ovulate.

Geir Helgemo tested positive for synthetic testosterone, considered a performance-enhancing drug among athletes, and clomiphene, a fertility substance traditionally given to women who do not ovulate.

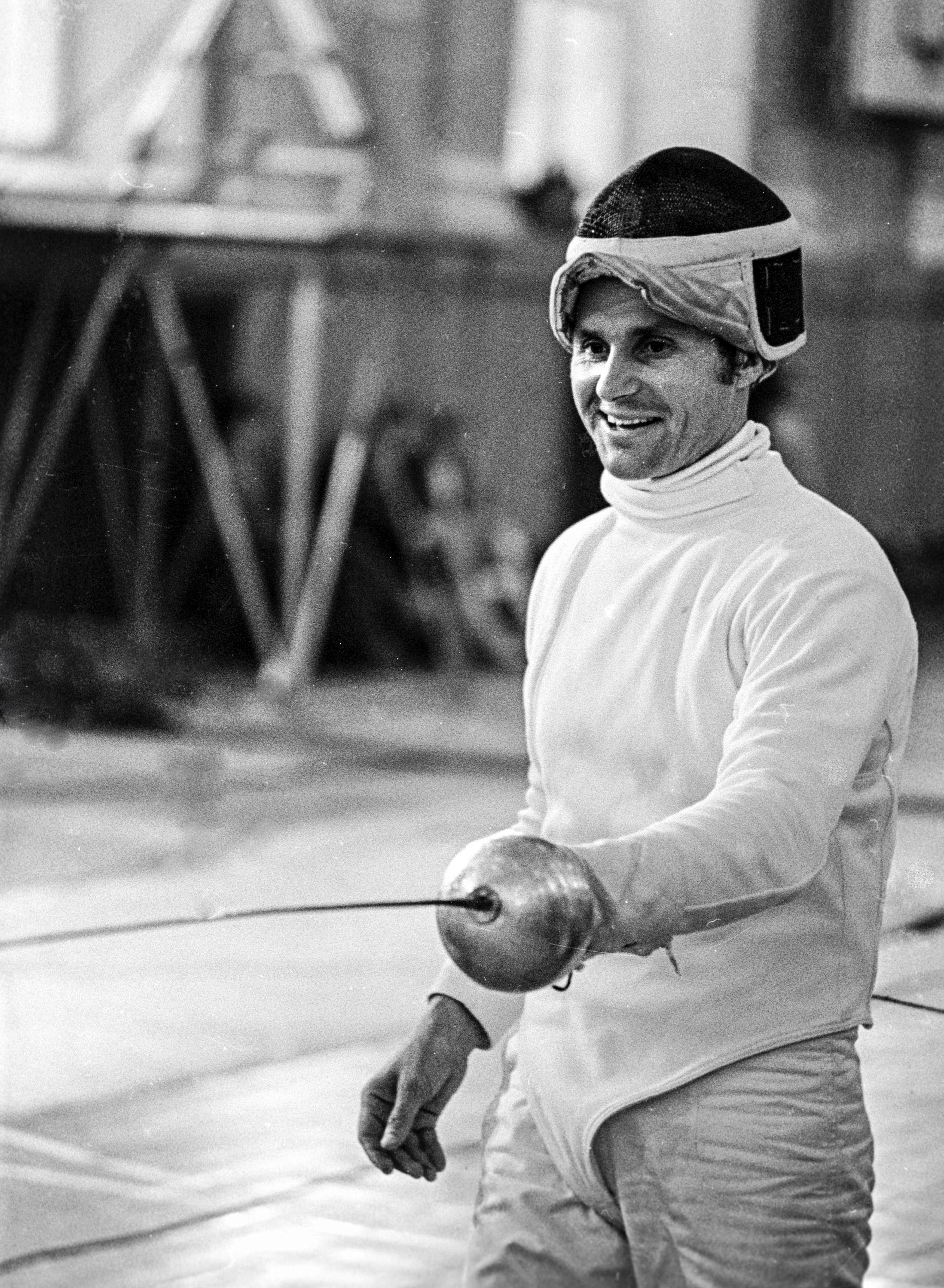

As clever as the German duo surely thought their scheme was, the prize for ingenuity must surely go to Boris Onishchenko, or “Disonischenko”, if you prefer. The Soviet pentathlete, the favourite to dominate the fencing event at the 1976 Olympics, was questioned when his buzzer went off without his épée (sword) touching his opponent.

After it was confiscated and examined, it was determined that the circuitry of the weapon had been modified to register points without the tip actually having to touch anything. Onishchenko was duly banned from the sport for life. The kicker? When the suspicion first arose and his sword was replaced with a legitimate one, he won the match with ease.

Boris Onishchenko. (Getty)

Boris Onishchenko. (Getty)

Of course, no conversation about cheating could be complete without talking about cycling. Its fraudulent poster child, Lance Armstrong, has always maintained that he was just one cog in a rotten machine. Many others have committed greater misdeeds than sitting in a trailer having blood cycled through them.

The very first Tour de France in 1903 was subject to misconduct allegations, but it was the following year’s edition that stands out as one of sports’ dirtiest-ever events. There was simply all manner of disgraceful behaviour.

At first it was the mobs — the most vicious of which came from Saint-Étienne and were supporting a regional rider. Cycling journalist Pierre Chany wrote: “A bunch of fanatics wielded sticks and shouted insults, setting on the other riders: Maurice and César Garin got a succession of blows, [Maurice] was hit in the face with a stone. Soon there was general mayhem: ‘Up with Faure! Down with Garin! Kill them!’ they were shouting. Finally cars arrived and the riders could get going thanks to pistol shots. The aggressors disappeared into the night.”

Much of the violence was speculated to have been set up by co-ordinated gangs. Other competitors are reported to have thrown projectiles at one another, felled trees to block the path and even littered the road with nails. Dick Dastardly, eat your heart out.

Hippolyte Aucouturier, victim of a spiked lemonade given to him by a spectator the previous year, decided he would leave nothing to chance and tied one end of a wire to a car and the other to a cork that he gripped between his teeth. Some of the leading pack simply hopped on a passing train with their bikes.

When all the cheating was tallied, the organisers punished 29 riders, including all the stage winners, and very nearly decided to scrap the annual race entirely.

With Italian Vincenzo Nibali disqualified for towing himself on a car as recently as 2015, has anything changed? The answer is yes: cheating is becoming more advanced.

The latest plague authorities are watching out for is technological assistance. The concept came to the fore in a big way in 2016 when Belgian Femke Van den Driessche became the first cyclist to be charged with “mechanical doping” after one of her back-up bicycles was found to contain a motor. Despite emotional appeals that the bike belonged to a friend who owned the exact same bike, and that it had been accidentally mixed into her pit, she was stripped of recent medals and banned for six years. Van den Driessche announced her retirement from the sport aged 20.

Michael Elinescu and Entscho Wladow were found by the WBF to have committed “the gravest possible offence” after using coughing as a way of communicating. They were given a lifetime ban from playing with one another and suspended from competitions for 10 years.

Michael Elinescu and Entscho Wladow were found by the WBF to have committed “the gravest possible offence” after using coughing as a way of communicating. They were given a lifetime ban from playing with one another and suspended from competitions for 10 years.

The truth is rarely as clear-cut as two German doctors coughing signals to one another. Some cheats find themselves disgraced, ostracised forever for what they’ve done. Others recover and go on to achieve much more in their careers. In some cases, it might even be the start of a legend.

The single most famous moment of cheating, after all, as English goalkeeper Peter Shilton in the 1986 World Cup would agree, came off “a little with the head of Maradona and a little with the hand of God”.