Man of his words: Masande Ntshangas novels are a reflection of his extensive reading and research. (Delwyn Verasamy)

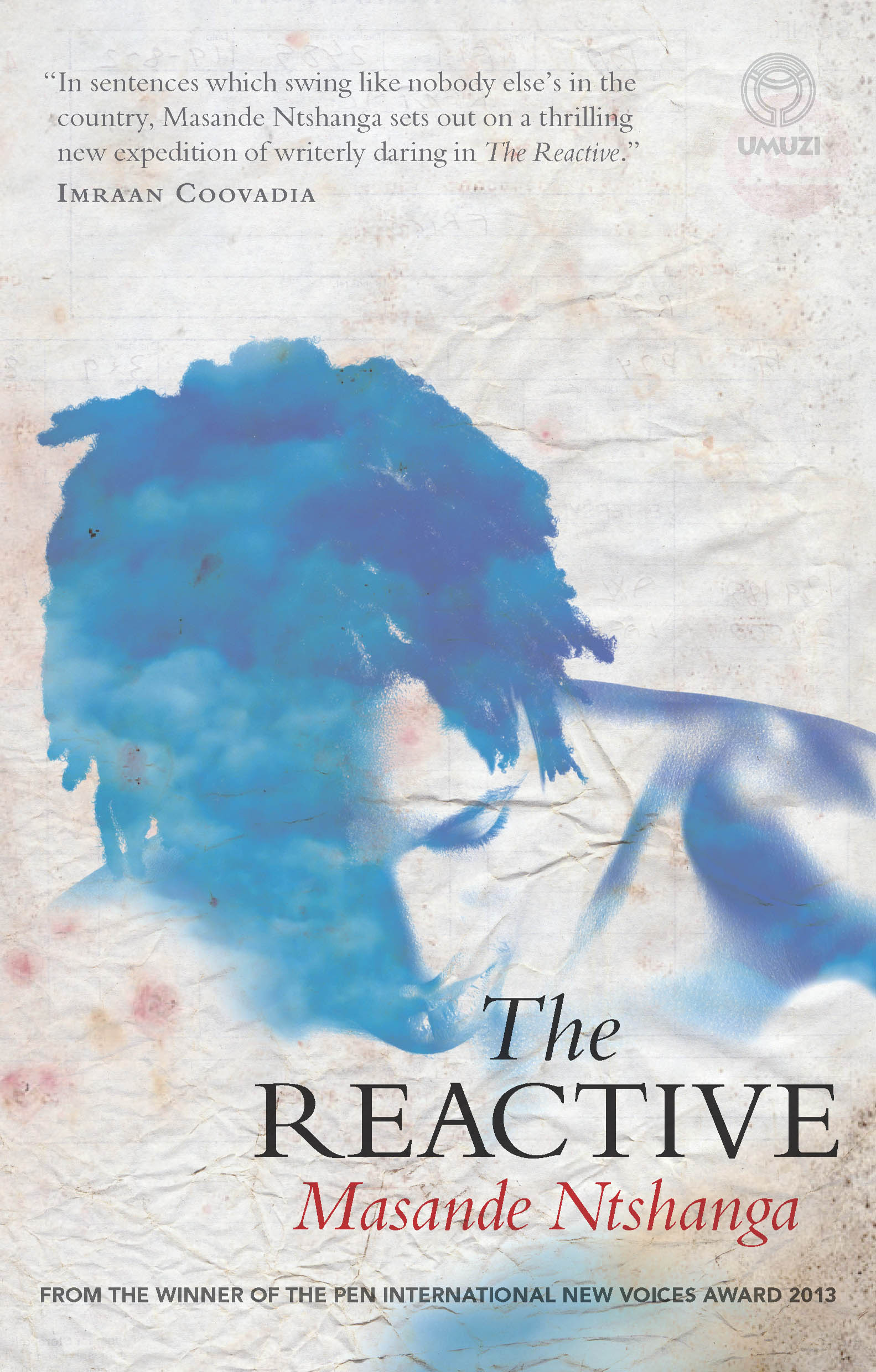

‘We have a tendency to take things for granted because we live here and because there are so many stories that get told about [South Africa],” says writer Masande Ntshanga. “So now there’s this idea that we can’t write books or fiction on apartheid anymore. I’m not sure about that.” Ntshanga is recalling an assertion he made shortly before writing his second novel, Triangulum, which follows his acclaimed debut, The Reactive.

While the process of many novelists and fiction writers is referred to as an art, it seems more fitting to refer to Ntshanga’s practice as a science. Just as hypotheses are speculations formed with limited evidence as a starting point for further research, so too is the genesis of Ntshanga’s writings.

The Mail & Guardian visited the novelist and fiction editor at his Johannesburg home to talk about South African fiction, nation-building, and developing a literary practice.

Ntshanga, dressed in a black turtleneck and faded blue Zara Man jeans rolled up to expose black socks, offers his guests a couch and sits at his desk facing us with crossed legs, his face resting on one of his wrists. He won’t be in Johannesburg much longer and is moving back to Cape Town. “It’s time.”

Since he was 15, the Bhisho-born Ntshanga has made it a habit to respond to the books he has read through writing fiction. “I started finding ones that I liked — things that were a very immersive reading experience — so much so that I actually felt charged and I wanted to write something of my own afterwards,” he says.

This practice continued when Ntshanga went to the University of Cape Town (UCT), where he majored in film and English literature. There he had access to the university’s African Studies Library and the rare books special collection, where he found a variety of “charged” texts that he “wouldn’t be able to find anywhere else”.

Ntshanga’s 17-year-long deliberate practice has seen him receive numerous awards, including the Betty Trask Award (2018), a National Research Foundation scholarship and the inaugural PEN International New Voices Award (2013), among others. Ntshanga received many of his awards after writing the short story Space, long before writing his two novels.

While his practice has earned him many accolades, Ntshanga says he has resigned himself to writing books that are commonly referred to as not being for everyone. “He’s serious and original about writing in a way that most even quite professional writers aren’t,” says Imraan Coovadia, the essayist and novelist who directs the creative writing programme that Ntshanga took at UCT.

Ntshanga remembers one of Coovadia’s seminars providing a pen-dropping moment that has since served his career as a writer. It was when Coovadia dared the creative writing class to imagine. “You want to believe that in fiction you can find all sorts of things through research, right?” Ntshanga asks. “But really, you have to be willing to dare to imagine how something would be and how it would feel for fiction to feel plausible.”

During the interview, it seems evident that Ntshanga’s limitless yet critical imagination is what makes it possible for him to revisit and revitalise South African themes such as apartheid, immigration, HIV, mental health, censorship, substance abuse and the sum of difficulties that black people have to negotiate.

“I write human stories about relationships and what those mean to us as people. But at the same time, in order to keep myself interested enough, it also has to be this intellectual undertaking,” he says.

This is achieved through a number of tools such as form, language, and spatial and temporal allusions, as well as referencing historical texts. One such text is The Ghosts of Lennox Sebe’s Ciskei, which Ntshanga read to understand the foundation of the Ciskei before using the homeland as a central setting in work. Written by Thembinkosi Lehloesa, The Ghosts of Lennox Sebe’s Ciskei tracks how Lennox Sebe, the homeland’s chief minister, became an agent of apartheid in the Ciskei while trying to attain independence.

The intellectual undertaking in The Reactive plays itself out through weaving societal issues into an intimate narrative using the protagonist’s voice. The novel is set in 2003, shortly before the announcement that antiretrovirals (ARVs) would be made available to the public. This is presented to the reader through a protagonist who has access to ARVs during this time but decides to sell them on the black market following his brother’s death.

Although there’s an expectation for the commonly visited subject of HIV to unfold through the played-out poverty porn lens, it unravels instead as a tale of grief and a search for the meaning of life inside a home of educated, black middle-class folk. In addition to encouraging the reader to reflect on access and healthcare in South Africa, Ntshanga’s delivery of this theme complicates existing ideas about how black masculinity manifests itself.

Ntshanga set up more of an intellectual challenge in writing Triangulum, although there are elements of this approach in The Reactive. “They’re different,” Ntshanga admits. “In Triangulum the narrator is more active, whereas I’m sure you can tell Nathi is a little passive as a character. I’ve even heard some people say that it’s more ‘voicey’ than Triangulum,” Ntshanga laughs.

Triangulum can be simplified as an exploration of intimate relationships in the context of mental illness. Following her mother’s disappearance, the unnamed teenage protagonist begins seeing apparitions that the medical system deems to be schizophrenic hallucinations. In essence, Triangulum explores how she relates to herself and her loved ones following her diagnosis.

This fairly straightforward plot is complicated through Ntshanga’s choice of genre and his experience of childhood, as well as the form of the book itself.

Firstly, Triangulum unfolds through the melding of historical fiction, science fiction and mystery. This can be seen in how the subplots unfold parallel to the Bantustan system being phased out in the 1990s, South Africa’s economic decline, the current state of surveillance — where personal information and movements can be harvested through your social-media presence — and the United Nations’ prediction of an ecological disaster in the 2040s.

Triangulum was sparked by the eerie mood of Ntshanga’s childhood memories of growing up in the Ciskei. “I remember in my first year of university, coming across this poem,” he says, before laughing at how he is haunted by forgetting its title and author. “The poet writes about this experience of apartheid feeling like a B movie… There’s this impression that it feels like you could be in a first world country but it’s artificial because there’s all this stuff that’s underneath the surface that’s really brutal and really violent.

“There was something about that poem that reminded me of growing up eBhisho,” Ntshanga says, recalling an underlying paranoia that made its way around the Ciskei in hushed tones.

In terms of form, both The Reactive and Triangulum shift back and forth between the present and the past because the author is uninterested in penning a linear reality.

“[The two novels] are preoccupied with recreating a simulation of experience so that you’re really immersed. I always thought linear narratives were too restrictive and too simple. I felt like it wasn’t true to how we experience life,” Ntshanga says. Triangulum takes this approach deeper by offering the reader a look at the future.

Ntshanga has bylines in Chimu-renga, Rolling Stone, The White Review, Vice and n+1, and his novels are available in more than five regions. In addition to South Africa, The Reactive and Triangulum have landed publishing contracts in the United States, the United Kingdom, Italy and Germany.

This business aspect of literature was not as a result of a deliberate plan of action on Ntshanga’s part. While he had wanted to be published internationally, he insists this played no role in his writing or the marketing of his work. The deals were a result of responding to opportunities. “I think that other regions, especially the US, respond to the form of the book,” he says. “I mean, they do have an interest in South African history but I only discovered that after publishing.”

Towards the end of the interview Ntshanga shares his thoughts on the idea of placing his work in a canon of fiction geared toward critiquing the state of the country, a practice that has generally been approached through realism.

“I mean, I really like realism but not necessarily in this strict tradition of social realism. There’s an amount of solace that I think can be derived from being able to experience plausible human interactions through reading,” he says.

However, Ntshanga also notes that his coming of age took place during, and was inevitably coloured by, the Truth and Reconciliation Commission, when devastating revelations were made with very few resolutions following them.

“I was always aware of these discrepancies in our society. So it was natural for me to put that into my stories. Not necessarily as a focus but as a context,” he says. “In a way, post-apartheid South Africa kind of critiques itself. I just have to transcribe what is happening.”