Serene grace:

For as long as Moshekwa Langa has been an artist, he has engaged with the task of mapping. His mapping has taken on a different form in his latest exhibition with Stevenson Gallery (Cape Town), titled Tropic of Capricorn.

Moshekwa Langa’s Tropic of Capricorn is currently showing at Stevenson Gallery (Cape Town). (Supplied)

The exhibition brings together large-scale works on canvas, mixed-media collages, portraits and paintings on paper. Historically Langa has explored land (Drag Paintings, 2016) and even the seas (Overseas I and II, 2017), however, with this show we see his playful mind unable to rest at a single point. Figurative works (Nketši and The Bully) are presented alongside collages (Broken Mirrors) and, even more excitingly, themes that leave the bounds of Earth and begin to engage the skies (Maitishong to Midnight I and Thunderstorm with Hail). It is this series of celestial works that I’d like to home in on.

In a recent interview with Langa, he emphasises the importance of beauty in this show. He says, “It’s interesting to work with things that are kinder to me visually,” speaking about why he is no longer interested in (re)creating images that enact secondary violence. He speaks of memories of looking up at the sky as a child and seeing the starry nights. These starry nights are reflected back to us in Tropic of Capricorn.

The artworks in this exhibition are not spectacular; rather, they are serene and graceful. Tropic of Capricorn can be thought of as a line that helps us understand the distance that the rays of the sun have to travel before they hit a specific point on Earth. The shortest distance that rays have to travel is to the equator, with each degree above or below the equator increasing that distance. In this case, we can think of light (sun rays) as a measure of time or, more accurately, warmth (sun rays) as a measure of time.

It is impossible to speak of Tropic of Capricorn without speaking about mythology. The myth of maps, of borders, of place and the myth of the lines outlining the tropics themselves. Lying about 23.5° north or south of the equator, lines of latitude (the Tropic of Cancer and Tropic of Capricorn) are named in line with astrology: Cancer (the sun reaches its zenith in the northern hemisphere on June 21 and Capricorn (the sun reaches its zenith in the southern hemisphere on December 21). But these dates are becoming less and less accurate due to the wobbling of the Earth’s axis through time. Latitudinal lines (although useful as tools) are, of course, completely fictional. They are mere measurements that do not actually exist on the ground or in the sky, similar to the many fictional lines drawn all over the world to separate here and there, us and them.

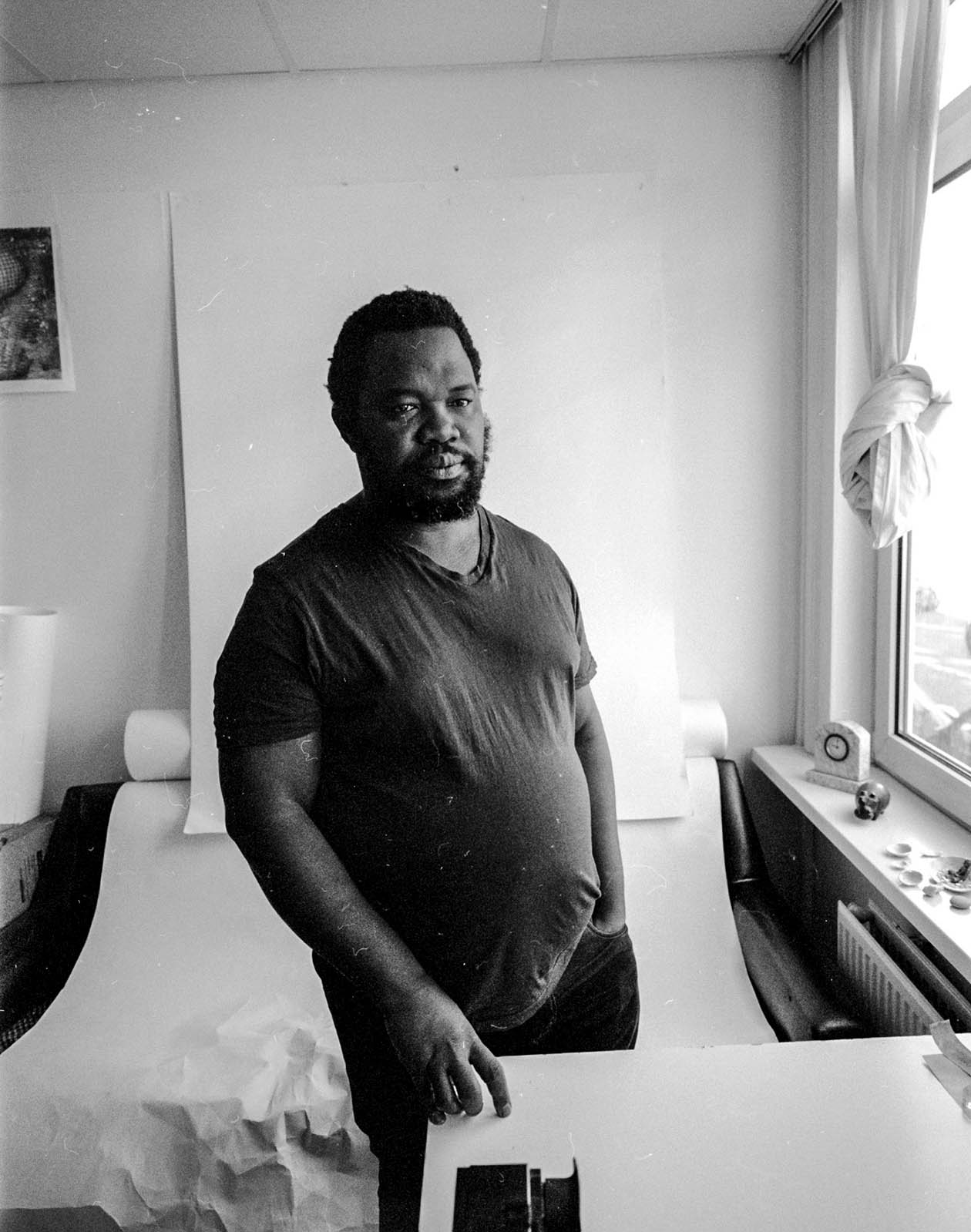

Playful mind: Moshekwa Langa’s Surrogate Portrait of Matlatša Rangoanasha, 2018, is part of his Tropic of Capricorn exhibition, in which the artist has ‘worked with things that are kinder to him visually’

Going back to the question of time, I quite like this idea of light and warmth as time, following theorists who believe that time is circular, with no beginning and no end. Conversing with Langa, one gains a weird sense of this circularity of time. He speaks about his work in relation to stories and, at times, it is quite difficult to know what point of his practice or life a particular story relates to. There is no linearity, or beginning and end, just stories that morph into each other; stories in which the present is reaching towards the future and the past is simultaneously then and now. Time is simply an internal experience.

Langa’s practice concerns itself with explorations of place and “placeness”. His origin story begins with being born and growing up in Bakenberg (which resulted in him being teased about coming from a hole in the ground because his hometown could not be located on various maps).

Bakenberg foregrounds our understanding of Langa’s explorations throughout his artistic career. However, the story of one’s life is not limited to the story of one’s origins. One is born, they grow up, they encounter different experiences and they evolve, “losing touch with a couple of people we used to be along the way”, as Joan Didion put it. It is for this reason that I wish to move away from Bakenberg as an entry point to reading Langa’s work and would like to propose a different one.

Earlier I mentioned the idea of time as an internal experience. If we can think of time in this way, then it might also be possible to think of space in the same manner.

Home, then, simply becomes different shades of the self, shades that are linked to internal memory and feelings. Just as Saint Augustine is said to have declared, in about 400CE, “In you, my mind, I measure time”, we can also declare, “In you, my mind, I measure place” or “In you, my mind, I measure home.”

If we follow this line of thinking, home for Langa becomes his mind’s creations; home is in Limpopo with his neighbour, Martha Mbiza, as much as it is in the depths of the seas and the expanse of outer space. Home is positioned nowhere and everywhere. But, of course, I recognise the limits of thought experiments, more so in a time of intense nationalist rhetoric, crackdown at the borders and the migrant crisis. It is not enough to simply declare in our minds where we consider home to be.

If, indeed, we are forced to speak of Langa’s work in terms of his origin story — the dusty streets of Bakenberg as the place where he comes from (travels towards and away from), then I’d want to point out the lyrical relationship that exists between dust and the beauty of mists and the clouds.

As early as the 19th century, scholars and researchers were beginning to formulate interesting ways of thinking through dust. In his aptly named essay The Importance of Dust: A Source of Beauty and Essential to Life (1898), Alfred Wallace writes: “The evidence goes to show, therefore, that the exquisite blue tints of sky and ocean, as well as all the sunset hues of sky and cloud, of mountain peak and alpine snows, are due to the finer particles of that very dust which, in its coarser forms, we find so annoying and even dangerous.”

“To the presence of dust in the higher atmosphere, we owe the formation of mists, clouds and gentle beneficial rains, instead of waterspouts and destructive torrents.”

Dust is a source of ridicule for Bakenberg. And yet, it is this source of ridicule that results in the beauty of the oceans and skies (the same ones we see mapped in Tropic of Capricorn). This relationship is poetic and, quite simply, beautiful.

Tropic of Capricorn runs until January 18