Pros and cons: Soya beans provide protein but mass production causes deforestation. (Yasuyoshi Chiba/AFP)

There’s a global push for people to become vegans, or at least eat less meat, to reduce their carbon footprint. Annerine Snyman looks at food production in South Africa and why not everyone could, or should, be vegans

Meat is a symbol of affluence. The more wealth people have, the more meat they eat. This means more fodder and water is required for livestock.

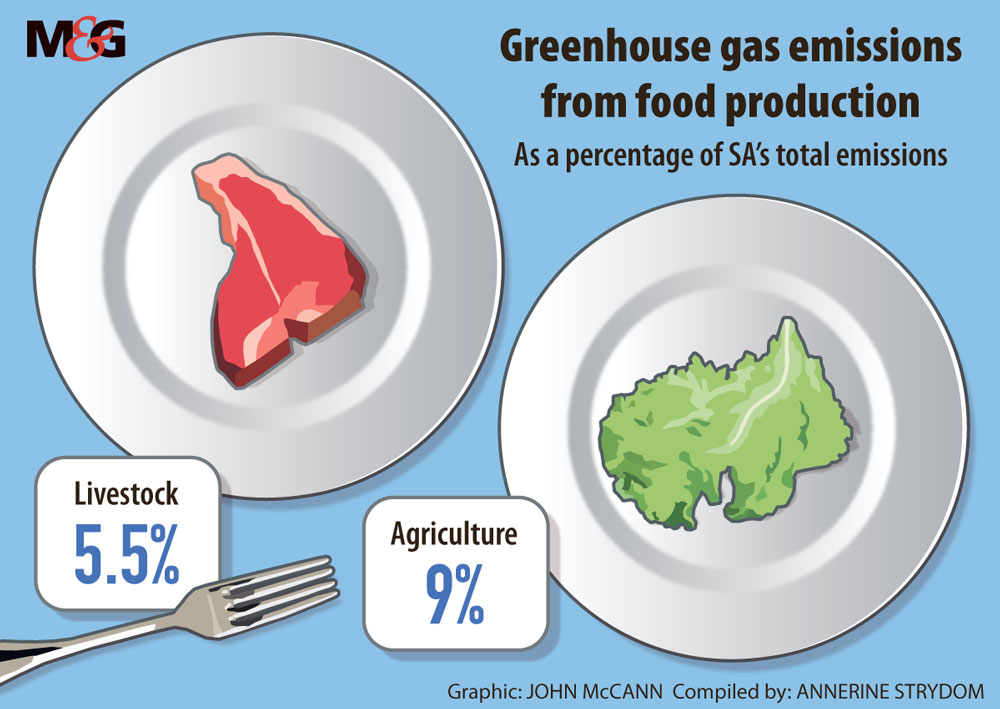

Agriculture in South Africa accounts for about 9% of greenhouse gas emissions, with livestock production responsible for 5.5%, according to Heinz Meissner, an adviser to, among others, the dairy and red meat industries. (The biggest culprit is the energy sector, which accounts for more than 70% of emissions.)

The climate crisis requires that global carbon emissions drop by 45% by 2030, and to zero by 2050. By not eating meat, people would contribute to reducing global warming.

But, in South Africa, this is difficult. Just 12% of the country has the right mixture of soil and water to grow crops, whereas livestock can live on marginal land — think of sheep in the arid Karoo. Fruit and vegetables are also expensive, and the higher their quality, the more expensive they are (and the more likely they are to be exported).

Meissner says land use and economics make it difficult to go for a vegan food system in South Africa: “We do not have the water resources and suitable soils to produce [enough] vegetables and fruit” and “from a GDP [gross domestic product] point of view, in terms of exports and so on, most of the water in irrigation will be used for high value crops such as grapes, citrus, avocados, nuts and blueberries to earn foreign currency, and will not be used for grains, vegetable and fruit production to feed the population.”

The Bureau for Food and Agricultural Policy, a nonprofit organisation, worked out how much it would cost a family for a basic, healthy diet in its “thrifty healthy food basket”. It found that a family of four needs a minimum income of R7 212, if 35% (R2 524) of total expenditure is spent on healthy food. The basket includes vegan foods — starch-rich staples such as maize meal, brown bread, rice, potatoes and wheat flour, along with fruit and vegetables (apples, bananas, oranges, tomatoes, onions, carrots, cabbage and pumpkin), legumes (dried beans and baked beans), as well as non-vegan foods, such as animal protein (beef mince, chicken, canned pilchards and eggs) and dairy products (milk, cheese and margarine).

If a family with two adults earn the minimum wage — R20 an hour — and works eight-hour shifts for five days a week, they will have a combined income of R6 400 a month. Which means they cannot afford a healthy food basket.

The cost of the shift to more South Africans living in cities and reaching middle class status was captured in a 2015 study, The Hidden Cost of Eating Meat in South Africa: What Every Responsible Consumer Should Know, in the Journal of Agricultural and Environmental Ethics. The authors found that more people were eating processed and high-protein foods, especially meat and dairy products. These foods require more land and water than fruit, vegetable and grain crops.

The authors said that “traditional agricultural farms” are being replaced with concentrated animal feeding operations, also known as factory farms, where the livestock are raised in a way that makes optimal use of space and other resources to maximise production and increase profits.

Goats can survive in arid areas. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Goats can survive in arid areas. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Maryke Gallagher, a spokesperson for the Association for Dietetics in South Africa, says a large part of the country’s food system is industrialised, which means it makes a lot of food that is affordable but has low levels of nutrition. These foods are non-wholefoods, which includes many canned or pickled foods with added salt and sugar.

As a result, she says, “A third of South Africans are food insecure with malnutrition in its various forms, a significant health challenge, while the prevalence of noncommunicable diseases [such as diabetes, stroke and cardiovascular diseases] and obesity are increasing.”

Data from the South African Food Sovereignty Campaign shows that 14-million people go to bed hungry. That’s a quarter of the population.

And, even though a vegan diet could potentially solve this problem, Friede Wenhold, from the department of human nutrition at the University of Pretoria, says that in terms of vegan diets, “one size does not fit all”.

She explains that such diets can be good options, noting that they are typically associated with lower kilojoule and fat intake, which can reduce the health risks of obesity and diseases such as heart disease and high blood pressure. Vegan diets are also higher in dietary fibre, which is “beneficial for most people”.

But Wenhold warns that these options are good only under certain circumstances and if foods are chosen carefully. “Long term adherence to veganism requires careful attention to protein intake. Animal-source foods tend to primarily contain the so-called high biological value proteins, as well as certain micronutrients that are associated with animal-source foods, for example vitamin B12 and iron.”

She says the items people choose to buy determine the price and nutritional value of their diet. “For example, one could choose to only consume a single type of food, such as maize meal porridge. That would be a vegan diet and very affordable, but certainly not healthy.”

Variety, she says, is key. And this makes it all the more difficult for people without money to stick to a vegan diet.

Meat is the most efficient source of iron and vitamin B12. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Meat is the most efficient source of iron and vitamin B12. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Gallagher says that the necessary nutrients can be obtained from a well-planned vegan diet, but in some cases, supplements — such as B12, iron and Vitamin D — may be necessary if dietary intake is not sufficient or a person doesn’t have access to sufficient dietary sources. These supplements can add extra costs to a diet and without taking these pills, it might be important for people to have “small amounts of animal protein”.

Nicola Kahvu, chef and owner of African Vegan on a Budget, says veganism is not yet possible for most people, because of the cost. Her business is trying to change this (while also being profitable) by making food more affordable.

Kahvu also says that a plant-based diet is something that was accessible and the norm for Africans, before colonisation. “I believe that veganism originated in Africa, to African black people, and it was never too expensive for us to grow and eat our own vegetables. But due to systems such as colonisation and just bad education, influences and practices, the vegan diet became expensive.”

Anda Mtshemla, author of the 24Karrots blog, says that most people think being vegan means eating quinoa, flaxseed and “a lot of things that not many people have access to”. She also says that many people are already eating vegan meals without realising it, because “it is not how veganism looks on Instagram”.

Mtshemla claims that a lot of lower income people aspire to eat more meat, because of the social aspect attached to it. “So, it is really about educating people to know that they shouldn’t really aspire to eat more meat. They probably just need to add more diversity of plants in their diets.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Red meat industry adviser Meissner says that veganism is limited to the affluent and middle class of South Africa. He says this group is estimated to be less than half a million, out of the nearly 60-million people in the country.

Some 70% of agricultural land is used for livestock production, and agriculture uses two-thirds of the country’s water. A heating planet — with increased variability in rainfall and droughts — means farming, which is a tough business, will become more difficult in the future. Increased efficiency in water use might mean there is more water for irrigation, which would allow for fruit and vegetable crops to be grown on marginal land. And, if more people become vegan, economies of scale will make growing these crops cheaper and more people will be able to buy it.

But, for now, a fully vegan diet is something that only a small number of people can afford.