Shattered dreams: The press conference in October at which Mmusi Maimane

As summer 2019 kicked in, the Democratic Alliance’s two most prominent black leaders resigned in a move many saw as pre-empting the house coup already under way. Bongani Madondo says the meltdown amid racial witch-hunting portends the beginning of the end of white liberalism itself

A poet of profound compassion, a voice festooned with spiritual ache on one hand, and the most wondrous of lilting cadences on the other, Don “Zinga” Mattera once wrote that “memory is a weapon”. The son of an Italian man — assigned the status of a white man in this country, and then based at Sophiatown’s Red Bus depot — and a Motswana domestic worker, Mattera would have a personal insight, experience even, about what that meant, born, as it were, out of a love song, a marriage of the West and the South, of black and white.

He would have had an acute understanding of the condition, then, of being a complex young African soul flowered in Western Township and growing up in Sophiatown, twin black enclaves a mere stone’s throw from white Johannesburg and yet virtually nonexistent to the majority of its otherwise well-meaning liberal dwellers.

This is not about Mattera. It is about us: a country he has devoted his deep love to, in the form of song, lyric, bitterest word-spit; for its unyielding insistence on the ethnic, class, gender and racial division of its children.

For Mattera, as for all poets worth their ink, South Africa then and now is a beautiful but deeply scarred country worth dying for. Better still, the country is an idea worth living for.

Memory is the weapon? Like most people, I do not always trust my memory. I do not always trust my memory, especially pertaining to the flighty, light trivialities of life: what our friends and families tend to remind us are the “happy moments”.

I do not always trust my memory but on the week the Democratic Alliance began its spectacular, its inevitable, road to political oblivion, announced through the resignations of its two most prominent black leaders, something pricked my memory. It has everything to do with former Johannesburg mayor Herman Mashaba. That week, two months ago, it felt as if everything had to do with Mashaba. Even after he had resigned it felt as if Mashaba’s shadow hovers over us, still: smirkfully. Finger-waggingly. Righteously.

Growing up as a laaitie and running around in the same Hammanskraal villages as Mashaba, who is a decade older than me, all of us young bucks looked up to him. We read about him; dreamed about his improbable rise to the top. His story was, quite simply, improbably gorgeous. If Mashaba, or even more poignantly, his heartstrings-tugging tale, didn’t exist, it’d hafta be invented. Here was one of us, someone whose parents’ house we passed on any given day. A man whose relatives our mothers went to church with. A distant big brother we never knew, whose nephews and nieces we went to school with.

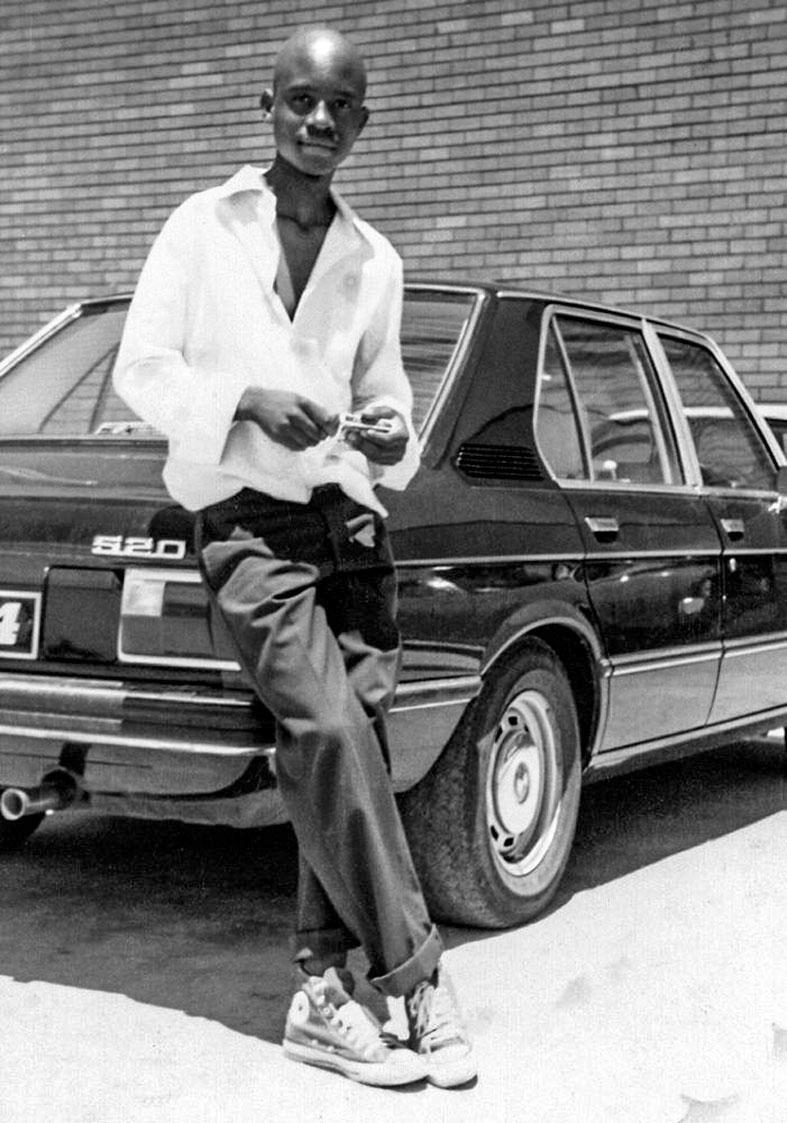

Herman Mashaba as a youngster.

Herman Mashaba as a youngster.

British soul diva Adele has an angel-rousing ditty titled Someone Like You. In Mashaba, here was someone like me. Someone whose dark skin and circumstances mirrored mine. Someone who was not born with a silver spoon, yet got out of the proverbial “dusty streets”, toiled sweat and blood, managing to kiss capitalism in its most exponentially booming growth decade, smack on the lips.

A man so astute, whip-smart and visionary as to name his company “Black Like Me”. It was simply a power move. Mashaba named it as such, in the era when blackness — regardless of the fact that there is actually no person coloured black, only variations of browns, reds, beiges, fawns — was still undergoing its psychic wounding phase.

Where, then, did he source the audacity to name his company that? How did he know that the mere gesture of naming came burdened with symbolism? Why did he assume he, and only he, could inspire millions of us through the treacherous process of naming? Devoid of love, a sense of history, the act of naming can easily lapse into shaming. Did Mashaba know something we didn’t?

We loved him madly. We loved him like a dream. It was not even love. It is never unadorned, unweighted love with us. It is heroism, grudging respect, fear, devotion, and all other emotions and thoughts coursing through the central vein of love.

Although we were born out of it, yearned for it, were taught about it, and in our teens whispered it to the opposite sex, on its own, love was unaffordable. Love was for the privileged. Love was for whites. Love belonged in the Bible with a Jesus with blond tresses and ol’ blue eyes.

Black Like Me: Herman Mashaba was the DA mayor of Jo’burg for just over three years, until he left last month — in one of the most dramatic gestures in recent South African politics. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

Black Like Me: Herman Mashaba was the DA mayor of Jo’burg for just over three years, until he left last month — in one of the most dramatic gestures in recent South African politics. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

How could we even love Mashaba when we hardly saw him around? He was a “big man” now, ensconced in his hair-manufacturing and distribution dream castle, a resident in the glossy magazines we peered at until our pupils became red and tears streamed down voluntarily. Ata Boy!

For decades I had forgotten about the village idol. Along the way, it also struck us that there were others who came before and after Mashaba.

Who can forget the stories of the great Habakuk Shikwane, the cane furniture genius, and his Afro-futurist architectural business premises, such as Afrispot, to drop but one name? There was an embarrassment of riches of achievers, especially in the relatively middle-class Leboneng freehold settlement dotted, as it were, with the traditional bougie class.

Fast-forward 30 years. As these things happen, three years ago I was assigned to profile Mashaba for this very publication. “Go hang with your homey,” was the editor’s brief. A stalker of black excellence, I pounced on it. We met at his family house in Athol. I was surprised to find it’s not a chateau in a magazine but a decent, well-decorated and art-filled house, in which real people and not rip-outs of magazine-celebrity figures lived.

In the living room was a huge-ass piano; my unreliable memory wants me to recall it as a Steinway. It was most probably a black baby-grand Yamaha Clavinova. He played some tunes. He’s not bad. He’s not Tchaikovsky, either. We conversed about Marvin Gaye. High-fived about Motown’s soul. And yet the nagging question persisted: How did a black man, even a supercapitalist like you, turn out to be a fundamentalist free-market exponent?

By the time I left, I had not drank the Kool-Aid of his neoliberal, capitalist beliefs. The politics of small government and/or keeping the government’s involvement minimal. Lovely on paper. Bad faith, in practice.

However, I could relate to the lessons of inspiring and enabling the poor to alter their circumstances through entrepreneurship, education and getting politicians off citizens’ backs to do as they wish within law. His politics were old-style black conservative, often African Christian conservative, pull yourself up by the bootstraps politics — simplistic but deeply persuasive.

He was, in a sense, not alone in this: he was part of the centuries old amaQoboka (cosmopolite, missionary-converted, and possibly the earliest black liberals in this country), cleaved by faith and orientation from their more radical, red-blanket kith, though never kin. I remember thinking about this when, a few years later, Mashaba was miraculously plucked from political obscurity and elected the executive mayor of Johannesburg with the help of the red-apparel-clad Economic Freedom Fighters. Aesthetically and perhaps in temperament, you’ll never find truer descendants of the amaQaba than the EFF.

A few years later I was not surprised to see Mashaba on a panel with then Business Day editor Songezo Zibi and the Institute of Race Relations’ Anthea Jeffery. The two had hot books out about the vagaries of black economic empowerment and that singularly South African theme: How did Mandela’s country slide so soon into the doghouse? But why was I on that panel? P’haps they needed someone to balance out a panel populated by liberal thinkers? If so, someone forgot to whisper to them that I, too, was a lib, if not politically, at least ideologically. We were all liberals and still are liberals, sometimes mislabelled “progressives”.

Although it raises eyebrows still, to be black and a liberal, even to be black and a radical humanist — which is not always synonymous with being “a liberal” — is not as shocking as being black and soul’d-out on liberalism, an aloof ideological mindset of the white elite.

The American all-purpose descriptor “democrats” might be useful, here. The most potent, nay, most dangerous aspect of the liberal philosophy, going back to John Stuart Mill — to 19th, 18th and 17th-century liberal philosophers such as the Egyptian Rifa’a al-Tahtawi up to the Englishman John Locke — is, as an ideology and theological philosophy, with gender and sexual politics et cetera, liberal politics will always be varied, inherently mutative, contradictory, deeply empowering, tragically inadequate, and ultimately responsive to its time. To wit, like its often confused first cousin, Marxism, it is also culture specific.

The panel was lovely, rowdy and quarrelsome. With the headline, “At South African Literary Festival, Broaching Uncomfortable Subjects”, that bastion of liberal traditions, The New York Times, reported that a black writer “looking at the audience attending a panel” observed: “There are a lot of white faces here.” The reporter didn’t say whether the speaker said it with ferocious anger and bulging veins, or, like Dave Chappelle sometimes, dropped the mic with a smile beaming from his face. “The audience laughed. Uneasily.”

Looking back, it would seem as if that year and that festival specifically was a watershed moment. It is at that festival that on a panel titled “Is Anger Underrated?” novelist Thando Mgqolozana laid down the gauntlet and told the audience: “I feel like an anthropological subject here and will never ever return here.”

Elsewhere sparks flew. Malaika wa Azania, Eusebius McKaiser and other “clever blacks” upturned the race tables, if momentarily, smashing exquisite porcelain to smithereens, spilling the red blood of Jesus (wine) all over the host’s chambers.

Time was up for that obnoxious notion of being the only darkie at the dinner table — and more so for his drenched-in-gentility host. After the day’s heated deliberations I bumped into Mashaba at one of the wealthy wine hamlet’s zhoozshy restaurants where the festival’s biggest party was afoot.

Accompanied by his wife, Connie, and the writer and activist Palesa Morudu, Mashaba was in a sparkling mood. Maybe he’s been touched by the book festival’s infectious zing, thought I. Conviviality reigned supreme. Enamel-white teeth were bared. Hugs. Hello, duh-lee-ng, why, isn’t this year rather hot? The place was on fire. So was Mashaba. Smooch, smooch. Wine glasses with slim, waif-like, supermodel-tall stems kissed mid-air.

Scanning the room, in that zippy- sharp and silent way members of the tribe I’ll call Black-Onlys are socially trained in — scanning not once but twice, thrice — I caught myself counting the number of black faces. We could not have been more than five.

I thought to point it out to Mashaba. Wrong time. The man was palpably joy manifest. He was excited about the DA, a party he had just joined. I remember he was particularly pumped up about the then 35-year-old Mmusi Maimane, who, a week earlier, had just been elected the leader of South Africa’s official opposition party, the DA.

Prior to that Maimane had pipped a seasoned colleague to the party’s mayoral nomination of the City of Johannesburg. A Setswana/Sesotho translation of the name “Mmusi” means “one who rules” or simply “ruler”.

It is a weird, little South African piece of historical trivia that a “boy” who grew up on the streets of Soweto; a “boy” who, by divinity or ancestral decree seem destined to be “a ruler”, pipped a colleague named Vasco da Gama on his way to city, then national prominence. Go figure!

‘Man,” Mashaba shoulder-bounced, before hugging me playfully with a strong, tight grip, “the writing is on the wall. It’s over. The DA is the party of the future. Come join us, man. It is not a white party; you media folks have it wrong. The DA is the future.” Because of the oppressive din in the restaurant, when he uttered, “the DA is the future, broer”, it felt like he was screaming. He was not. It was the venue’s acoustics. All eyes turned to us, and sharper ears caught his last evocations “party of the future, no doubt”.

Slightly more than a year later, on August 22 2016, Mashaba was sworn in as the executive mayor of Johannesburg, a position his friend and now party boss had coveted just a year earlier. Exactly three years and a month later, Mashaba announced his resignation from both party and the mayorship.

It was simply one of the most earnest and yet dramatic boom-bye-byes in recent South African political polity. A radical protest gesture only a wealthy man or a black man who would not be shown his place would undertake. Twitter went apeshit, exploding in 280-character jeremiads.

In truth, the DA has been on a slow spin, haemorrhaging supporters for more than a year, mainly for two reasons. Firstly, in 2017 the ANC elective conference elected Cyril Ramaphosa as party leader, and by extension, first citizen of the country. In a period characterised by political theatricality, costumes and all, a social media boom, power cuts, a currency in tailspin, junk(yard) status from global rating agencies in the air, Nasrec 2017 proved to be both a cliff-hanger and a voluble sigh, anticipative of a thud-ful crush that never happened … only a gradual descent.

By December 2017, everyone had known that the ANC had fully become a party of gangsters. It was also a party of hundreds of thousands of “decent” members who were either maimed into silence, remained tone deaf or, simply, were enthusiastically “unseeing” while its leadership not only looted the country, but also, even more treasonously, enabled foreign capture on a scale unseen since the halcyon days of Mobutu Sese Seko and the oil pashas of Nigerian politics.

By pulling the country away from the edge of the slippery cliffs overlooking the heart of darkness South Africa has always been expected — like its fellow African countries — to plunge into, the party managed to buy itself a temporary future and new Day-Glo.

It also assigned its smaller but noisier political rivals and their schoolyard antics to near obscurity. Not so fast. Let’s wind the clock back to six months before Nasrec 2017.

Writing in the Sunday Times op-ed section, the DA’s then chief whip, John Steenhuisen, crowed in an opinion piece: “The ANC is at its weakest … The house of cards built on the foundations of ANC capture by the Guptas is beginning to fall. The ANC is tearing itself apart in fits of factionalism as the fight for spoils rages unabated.” Nice touch. Poetic. “House of cards built on capture … ” “Rages unabated.”

It’s no secret that under former president Jacob Zuma and his merry bands of filthy pirates bloated with greed, lucre and avarice, the ANC had stopped being a “broad church” of ideological contestations, and had fully signed a Faustian pact with the devil. It would not be long, though, before the devil was on the run and living it up in the “Hong Kong in the desert”, Dubai, and Zuma and his cronies reduced to B-movie villains at the Zondo commission, which Zuma himself had played a role in instituting.

Secondly, and according to the same issue of the Sunday Times in which Steenhuisen flexed his poetic gifts, the DA’s own internal poll warned the party that it had lost the faith of its black supporters or vice-versa. Thanks to its indefatigable, then former-president Helen Zille, nicknamed “The Terminator”, and her colonialism apologist tweets, the DA’s not-so-hidden history of racism was, once again, foregrounded.

It was not so long ago that the DA fought national elections with a double-entendre slogan, “Fight Back”, a too-clever-by-half message considering the country’s combustible sensitivities about race.

But instead of apologising, Zille doubled down and dug into her bottomless tote bag filled with all sorts of curious, 18th-century, race-baiting nuggets. Earlier this year the party was duly punished, with its share of the national vote declining from 22.23% to 20.77%.

Lots of political hokum, faux pas and plain old dagger-in-the-back dark arts have happened within the DA, of course: the Western Cape-based, Xhosa-speaking Zille made a dramatic comeback in October this year when she pipped the Xhosa-fluent Athol Trollip from the Eastern Cape to snatch the position of federal council chairperson. Mashaba who, with Maimane, had long distrusted Zille’s political ambitions after her “retirement” and disdained her supremacist leanings, resigned from the City of Johannesburg in protest.

The Terminator: DA federal chairperson Helen Zille.

The Terminator: DA federal chairperson Helen Zille.

Thus spun the “guardian angels” of South African liberalism. Harry Schwarz, even Frederik van Zyl Slabbert and Joe Seremane, and Steve Biko — whom she’s in the habit of evoking — are spinning in their graves.

Mashaba was followed by Maimane, who hoped a mini-commission he instituted to investigate the causes of the party’s decline in the 2019 national elections — probably under the impression that the results would point to Zille and the party’s opposition to honest discussion about race and class matters — would exonerate him, but instead it lynched him out of the party.

Maimane, the young black man who was parachuted, without experience, to window-dress the DA into the future; Maimane who was recruited as a mascot of the blue wave — which, with the projected support of masses of “clever blacks” from the professional class, fancied itself a government-in-waiting — was lynched to save Zille’s skin.

In other words: isn’t it too cute a coincidence that the party’s “leadership review report”, the contents of which never pointed a single finger at Zille, dropped to coincide with her return to active, national politics?

Nah, c’mon, all these events just happened out of the blue, right?

What does all this mean for the South African liberal project? Globally, liberalism and its progressive and leftwards social-democratic advances are under attack. Liberalism is not only under attack from white supremacy or Stalinist centralism: it is eaten from inside its gut by its right-wing constituency.

In South Africa one thing is clear: the DA will never again be a political force. With the slow death of the custodian party of white privilege and white guilt, whiteness itself will do what it does best: fortify itself into little laagers, oblivious to the fact that its enemy is right within.

South Africa needs a radical, honest, multidimensional party with staunch, 21st-century, intersectional liberal resolve. A party — certainly a grassroots-to-middle-class-aligned movement — as committed to policy as it is to hearing the cries and howls of the poor, black people and women.

A party for a changing country beset with spirit-debilitating woes brought about by the ANC and stubborn white privilege, in the last- quarter century of the sulky, often fatal dance. Herman Mashaba’s once-beloved Democratic Alliance is clearly a party of the past. If my memory serves me well, my homey had lied to me.

Bongani Madondo is the author of Sigh, the Beloved Country (Picador Africa). He writes about poetry, photography and power dynamics