Queering the archive: Jewellery designer Githan Coopoo uses the performative nature of fashion to address a number of societal issues. (David Harrison/ M&G)

It isn’t enough to describe Githan Coopoo as a Cape Town-based jewellery designer. Something about the description feels curt, impersonal and incomplete. After a handful of texts and an hour long phone call, the inkling has grown to feel like a verifiable judgement.

“The past few days have been quite busy,” Coopoo sighs over the phone. It’s the week after the Design Indaba. Coopoo has just wrapped up the paperwork and interviews that come with being nominated for the most beautiful object in South Africa. In the middle of it all Coopoo launched a collection at the A4 Arts Foundation’s experimental retail space, proto~.

After completing a BA in English and art history at the University of Cape Town, Coopoo worked as an assistant curator of costume at the Zeitz Museum of Contemporary African Art. They left that scene to be a fulltime jewellery designer.

As an introduction to the public, Coopoo’s Instagram biography describes their practice as “queering the archive and unpacking the performative nature of dress”. This was informed by Coopoo’s need to acknowledge the presence of queerness in South African history and, more specifically, their Indian and coloured heritage. “I grew up very aware of my heritages but the queer was erased,” Coopoo says.

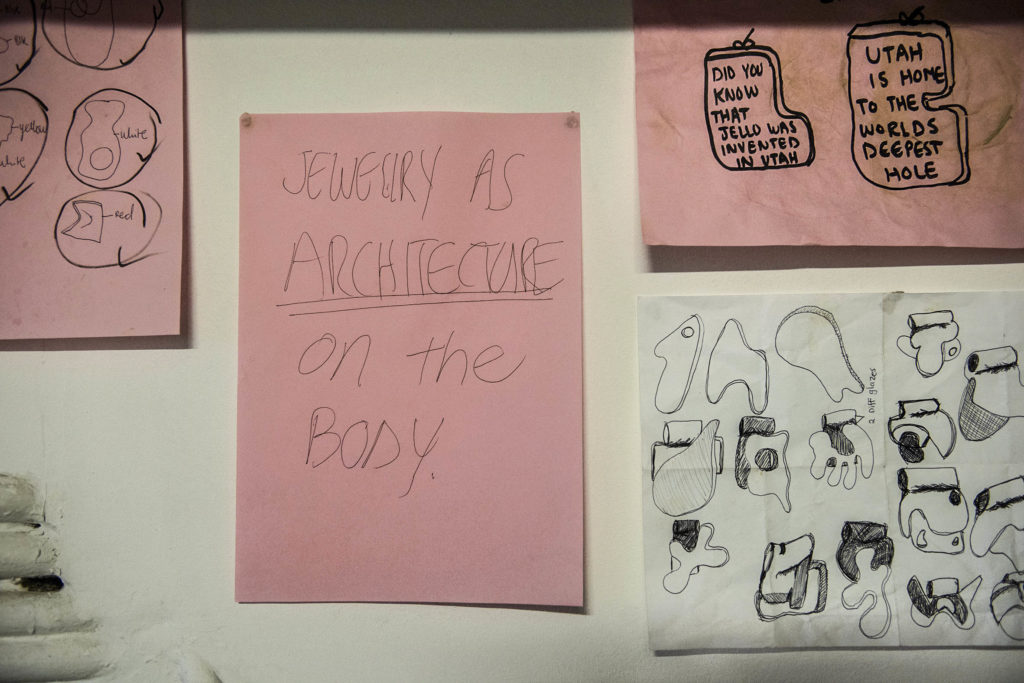

If it had to be described, queering the archive through dress would refer to the “very performative act of putting on clothes, adorning and modifying the body” in a manner that does not observe gender-conforming protocol. To embody queering through fashion, Coopoo says clothing and accessory items must be understood as being fluid and without limits. “There’s no wrong answer … they’re just objects that engage with the body and I’m interested in further unpacking this idea through my work.”

Githan Coopoo uses their practice to test the limits of adornment. (David Harrison)

Githan Coopoo uses their practice to test the limits of adornment. (David Harrison)

In a move to unpack the idea of there being no mistakes, Coopoo makes objects that represent and celebrate queer energy. “It’s something that we could use to identify, validate ourselves and feel fabulous with.”

https://www.instagram.com/p/B9gKDD4JxwH/?utm_source=ig_web_copy_link

But it isn’t just the gender-nonconforming nature of their work that makes it queer. The queerness is also in how unafraid Coopoo is of reimagining any and everything into a necklace, a brooch or a pair of earrings. The objects range from representations of blue fine china, cigarette stompies, lemon slices and Hellenistic-style bulls. With regard to size, Coopoo’s jewellery go from the circumference of a R5 coin to that of a ramekin.

Even though the target market is clear, Coopoo is aware of the affordability issue at play when the accessory prices start at R1100.

To address this, Coopoo is looking to invest their earnings into queer, mental health and HIV advocacy work once the brand begins to thrive. “I want to use the money that I make to talk about the things that I actually want to talk about,” Coopoo says, before admitting how hard it is to have public discussions about pertinent issues because of relentless and systemic queerphobia and invalidation. “Queer people do not exist in a capacity that allows them to feel empowered.”

With regard to the social function of their work, the objects mirror Coopoo’s delicate nature. While being “deeply depressed and hating how sensitive and vulnerable I was”, the work became a material intervention for survival. “There was a day when I realised that it wasn’t okay for me to try to fix myself while being happy and willing to let my work break.”

Since then Coopoo has continued to work with this medium, knowing how fragile ceramic jewellery is. “It’s about feeling and wearing the weight of your emotions. We are fragile, sensitive, porous, broken and subject to the elements that are beyond our control.”

The jewellery’s fragility adds to its value, because those who are likely to buy it would want to keep it safe and avoid it being damaged.

March 10 2020 – Githan Coopoo. Photo by David Harrison

March 10 2020 – Githan Coopoo. Photo by David Harrison March 10 2020 – Githan Coopoo. Photo by David Harrison

March 10 2020 – Githan Coopoo. Photo by David Harrison March 10 2020 – Githan Coopoo. Photo by David Harrison

March 10 2020 – Githan Coopoo. Photo by David Harrison

Shape of my heart: Githan Coopoo’s fashions jewellery pieces that mirror and celebrate their vulnerability. (David Harrison)

It wasn’t always like this. There was a time when Coopoo’s practice was driven by an “aesthetic and materialistic” demand because they couldn’t find anything they wanted. “Clay was accessible, easy to work with and allowed me to create big and voluminous shapes without having to work with metal,” Coopoo adds. Then Rich Mnisi asked them to make jewellery for the Rich Mnisi show at the 2017 South African Menswear Week.

But, after being dealt a series of disarranging circumstances last year, Coopoo turned to their work for refuge. “That’s how my mother raised me: when we are met with difficulty, we have a powerful capacity to transcend by applying ourselves to things that we find solace in.”

Another integral part of the process is how Coopoo works alone and makes items by hand, without the help of moulds. The process determines the speed of the output. This is a deliberate part of Coopoo’s practice, because they are trying to slow down consumption in the fashion and retail industry. “We’re so invested in taking in things at such a rapid rate that we don’t acknowledge and appreciate what we’re ingesting. I don’t want to encourage the mindless purchasing I see happening. Hopefully my practice slows capitalism down.”

Handmade: The artist’s work looks to slow down the rapid rate of consumption in the fashion industry. (David Harrison)

Handmade: The artist’s work looks to slow down the rapid rate of consumption in the fashion industry. (David Harrison)

In addition to physical, wearable items, Coopoo’s Instagram account is a virtual but integral extension of their practice. Inasmuch as it functions as an online storefront, Coopoo also the app to further their radical softness and queer joy agenda.

Most of Coopoo’s posts are editorial or at-home shots of their work, because “I actively need to market myself”.

To fulfill its second function, there are snapshots of celebration scattered across their Instagram feed. A handful of the posts are candid makeup selfies that reference their Desi and Hindu descent. Others are full body pictures taken in the middle of convenient stores to show off the elaborate outfit they pulled off on a particular day. The rest are Coopoo’s loved ones blushing to the camera, nights out, flowers, artwork, as well as congratulatory posts featuring excelling queer cultural practitioners like Mnisi, Thebe Magugu and Faka.

Even though the posts aren’t planned, their moods are deliberate, because Coopoo sees celebration and positive affirmation as powerful tools for the Indian, coloured, “HIV positivity advocacy”, queer and fashion communities that they are a part of. Coopoo mentions how, in spite of them presenting a probability of harm, platforms such as Instagram allow those who are marginalised to subscribe to and become a part of the communities that uplift them. “So when something really matters to me or I feel really beautiful in a moment, I post it. I really do want us all to be happy at then end of the day.”