The Ashley Kriel Detachment was among the most successful in Umkhonto weSizwe (MK), the seven units having carried out more than 30 operations between 1987 and 1990. (Courtesy of Nadine Cloete)

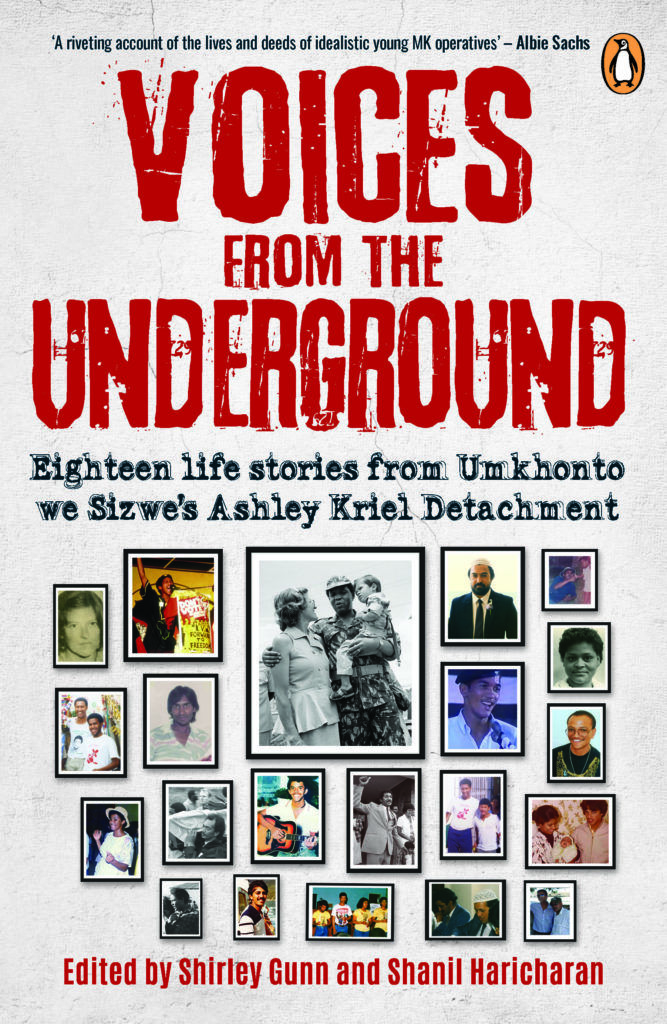

The book is divided into eighteen chapters, with each one dedicated to a different member of the detachment. (Penguin)

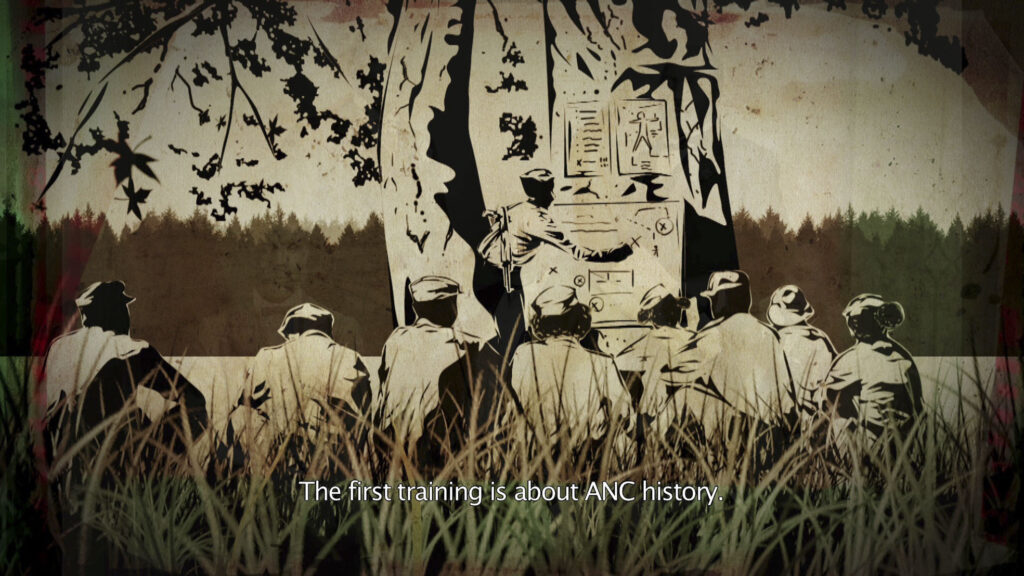

The book is divided into eighteen chapters, with each one dedicated to a different member of the detachment. (Penguin)Voices from the Underground: Eighteen life stories from Umkhonto we Sizwe’s Ashley Kriel Detachment is the story of one of the most successful Umkhonto weSizwe (MK) detachments to have operated. The success of the detachment may be attributed to the fact that different members were trained inside and outside South Africa, some as far as Cuba. The geographic spread of their operations was far ranging, with seven units having carried out more than 30 operations between 1987 and 1990.

The book is divided into eighteen chapters, with each one dedicated to a different member of the detachment. Members tell their own stories. Not all members’ stories are included, though. Coline Williams, Robbie Waterwitch and Anton Fransch lost their lives in the line of duty. Richard Ismail was murdered in 2007, and Paul Endley and Andrew Adams passed away before the book interview process began. Then there are four members who the Ashley Kriel Detachment (AKD) cut ties with because of suspicions that loyalties had been compromised.

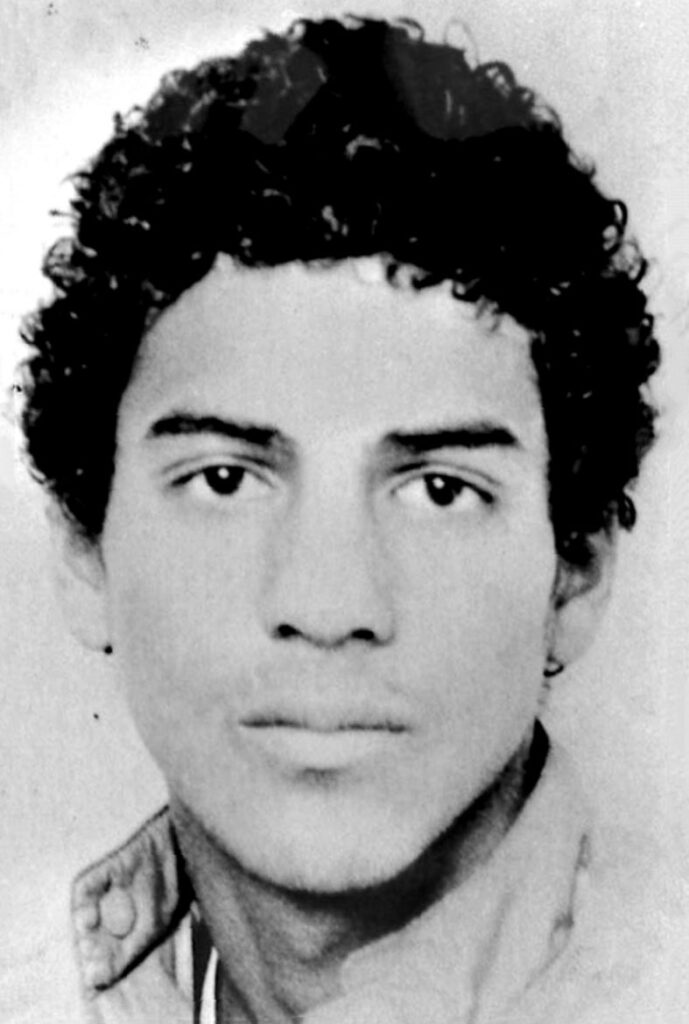

The unit was named after and inspired by Bonteheuwel activist and MK soldier, Ashley Kriel, who worked hard to conscientise 1980s working-class youth to stand up against the apartheid regime. He was a well-loved leadership figure among working-class youth in the Western Cape. He was also working in the MK underground and became a target of the security police.

The unit was named after and inspired by Bonteheuwel activist and MK soldier, Ashley Kriel, who worked hard to conscientise 1980s working-class youth (Supplied by Penguin)

The unit was named after and inspired by Bonteheuwel activist and MK soldier, Ashley Kriel, who worked hard to conscientise 1980s working-class youth (Supplied by Penguin)

Kriel did military training in Angola and was selected for further officer training abroad. He came back into the country, though, and was murdered by Jeffrey Benzien in July 1987 at age 20. Kriel’s murder ignited many people to continue the fight against the unjust system. His legacy lives on, even infiltrating pop culture today. YoungstaCPT makes reference to Kriel in his song, The Cape of Good Hope, rapping that he is being aggressive for the slain hero.

All the chapters of the book follow a similar formula: an anecdote at the beginning, the comrade’s background, their own radicalisation, how they joined the detachment and their present life. One doesn’t necessarily need to read the chapters in chronological order, but each one seems to provide context to the one that follows it.

Some pages fly by while others require you to sit with the detailed descriptions for a while, especially if you understand things in a visual way and need to imagine scenes playing out in front of you before you’re able to turn the page.

Progressive family members, religious leaders and teachers representing various political movements played a huge role in politicising young comrades. Seiraaj Salie reflects on what it was like having the author Richard Rive as an English teacher at South Peninsula High School: “He also talked about ideas like Négritude in America, and about writers such as Chinua Achebe, James Ngugi, James Baldwin, Langston Hughes and Nadine Gordimer, as well as the Sestigers …” Rives’s own work was banned at the time.

When considering the different stories, what strikes one is how the radicalisation of each individual happened relatively independent of the others. Many of these comrades share moments that shaped their social consciousness, presenting us all with a moment to reflect on what has shaped our own.

Shirley Gunn came to realise how poverty and health intersect when she visited the sickly in areas such Vrygrond and Nyanga with her mother, who was a nurse at Groote Schuur hospital at the time. When Gunn did her own nursing training, she saw how black hospital wards were understaffed and overcrowded. Aneez Salie touches on how his first political lesson was standing with other students in grade one and not singing Die Stem; his second, promising to avenge anti-apartheid activist Imam Haron’s death. The Imam died in a police cell in September 1969 after 123 days in solitary confinement. His family is still demanding the truth about his death.

Vanessa November speaks about politicised spaces such as the Bonteheuwel Civic Centre, which was called Freedom Square (there now is a move in the community to recognise this space as part of national heritage). It was the rallying point for action: “When we held the rent boycott that year, we met at Freedom Square with dirt bins we’d collected on our way from school and we pushed our way into the rent office and dumped the trash inside.”

The effects of the deaths of AKD members still reverberate across South Africa today. Each comrade affected by these deaths takes the space in their chapter to unpack them. There are feelings about how Williams’s and Waterwich’s deaths could not have been an accident. They were killed while on a mission to plant a limpet mine. Aneez Salie, especially, discusses the three possibilities around how they could have been killed. Melvin Bruintjies’s words strike as hard as a Rupi Kaur poem: “They were faithful to the end.”

Fransch was sold out and the chronology around this is made clear in the book. Still there are unanswered questions. Again, Bruintjies asks why the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) did not approach Aneez Salie and Gunn to provide more detail about how Mark Henry (the man held responsible for selling Fransch out to the police) compromised the detachment. Charles Martin states about the TRC that, in some cases, it ended up giving credence to “a type of cheap grace”. No moment is romanticised. Comrades mourned, but had to carry on the fight.

At times, one wishes writers would delve deeper into their experiences. Some chapters feel very plot driven at points. One understands this and the broader significance of the book better when reflecting on Gunn’s words: “We had survived in the underground for a number of years and I don’t know if words can adequately describe the toll it took on us — we never talked about it and we didn’t consider the personal cost. Some of us are only beginning to reflect on this now.”

A few comrades write honestly about having to take antidepressants, seeking psychological help, marriages failing and the struggle of adjusting to civilian life after being part of the underground. This is the side of the unselfish sacrifice that we don’t hear much of. Comrades also had to grapple with the guilt of injuring a civilian during one of their operations and appeared at the TRC for this.

There was also love, as Kim Dearham writes about her and Mike Dearham: “He gave me banned literature to read in-between all the smooching, and I specifically recall reading about Winnie [Madikizela-]Mandela’s personal sacrifices as a woman and mother …”

When the ANC was unbanned and Nelson Mandela was released, the AKD remained active. They believed Mandela made it explicit in his public statement on his release that the armed struggle would not be abandoned. They bombed symbols of oppression, which included the Newlands cricket ground, where a rebel tour was set to take place; and the Parow Civic Centre, where a right-wing Afrikaner Weerstandsbeweging meeting was scheduled to happen.

The success of the detachment may be attributed to the fact that different members were trained inside and outside South Africa, some as far as Cuba (Courtesy of Nadine Cloete)

The success of the detachment may be attributed to the fact that different members were trained inside and outside South Africa, some as far as Cuba (Courtesy of Nadine Cloete)

Comrades lived in hypervigilance and rightfully so, as Gunn and her son Haroon, a baby at the time, were arrested in June 1990. At a young age, Haroon experienced 62 days in captivity.

Many comrades expected life to be different with the onset of democracy and voice this clearly in chapters. They stayed underground until receiving legal indemnity in 1991.

It was an immense honour for me to tell Kriel’s story in the documentary called Action Kommandant. Through the journey of producing the film, I met some of the people featured in the book. I thank them for the contributions known and unknown they have made to my life.

I have had interactions with Haroon Gunn-Salie, Gunn and Aneez Salie’s son; as well as Tracey-Lee Dearham, the oldest daughter of Mike and Kim Dearham. To them and to all the children of those on the frontline, I want to salute for your immense sacrifice too, perhaps something we’ll never fully understand; perhaps something this book gives the broader public a chance to grasp.

Writing this review during a time of lockdown, I feel we really only have a small taste of what these comrades went through. The book honours their sacrifice. When screening Action Kommandant at schools educators ask me about learning resources. There aren’t many specifically about Kriel and his community. If anything, in a time of decolonisation, see this book as a primary source telling the history of those in service for our liberation.