Frank B. Wilderson III standing in front of Vista University campus in Soweto, where he was a lecturer. This image is taken from an article written by Wilderson and published by Tribute magazine in 1994. The article exposed links between Vista University and the Broederbond. (Supplied)

People who approach racial slavery as just an event in the past will experience Frank Wilderson III’s book, Afropessimism, as a violation. In his own words, they will encounter “Afropessimism as though they are being mugged rather than enlightened; that is because they can’t imagine a plantation in the here and now”. Yes, even in the here and now of South Africa.

(Supplied)

(Supplied) Set in Minneapolis, New York and Johannesburg, Afropessimism was released on April 7. This was two months before the streets of Minneapolis were set ablaze as a result of the video-recorded lynching of a Black man, George Floyd, whose brutal murder was beamed on to our screens and played on repeat across the world. At that time, the author could not have known that a harrowing scene around the corner would fit into the book’s agenda like a hand into a glove.

In 1991, Wilderson, who grew up in Minneapolis, was the second African-American to be elected into the official ranks of the ANC. (The first was Madie Hall Xuma, who was the president of the ANC women’s league in 1943.)

Wilderson is professor and chair of the African-American studies department at the University of California, Irvine. He is a poet, filmmaker and the multi-award-winning author of Incognegro: A Memoir of Exile and Apartheid (2008) and Red, White & Black: Cinema and the Structure of US Antagonisms (2010).

The title of his third book also refers to a school of thought that critiques civil society’s naturalised dependency on anti-Black rituals of violence. Amid the current international Black Lives Matter protests that are leading to the toppling down of the statues of slavers and imperialists, the Mail & Guardian interviewed Wilderson on his latest book and the genesis of Afropessimism as a field of thought. This is part one of a three-part interview.

Zamansele Nsele: You were born in New Orleans and raised in Michigan and Minneapolis, Minnesota. In your adult life you move to South Africa in the late ’80s, during a time of intense political upheaval. You become a card-carrying member of the ANC and you get involved in its armed wing — Umkhonto weSizwe (MK). Can you tell me about your political activities in South Africa during this period?

Frank Wilderson: When I came to South Africa in 1989, I joined the ANC as a normal cadre (either December 1991 or early January 1992). I later became an elected official in the Hillbrow/Berea branch; then I was elected to the five person ANC subregional executive committee for Johannesburg and the 16 townships that surround it.”

At the same time, I was a member of the ANC regional peace commission. In the commission we worked to document the atrocities committed by [FW] De Klerk’s security forces and the IFP [Inkatha Freedom Party]. I did this work at the peace commission but, covertly, it was linked to MK. In MK we smuggled rifles into the townships in the Vaal Triangle and to the East Rand area so that our people could combat the police, the SADF [South African Defence Force] and the IFP.

I was also on the executive of the Workers’ Library, a communist library and resource centre where anybody with any affiliations — whether you were Pan-Africanist, whether you were non-affiliated, whether you were a Charterist — anyone could attend the communist seminars. We would bring people like Ronnie Kasrils or people from the PAC [Pan Africanist Congress of Azania] to speak.

In addition to that, I was elected to the executive committee of Cosaw [Congress of the South African Writers], where I was nominated by Nadine Gordimer to take her position on the executive board. And I worked as the assistant director of an NGO [nongovernmental organisation] project (run out of Khanya College), where I organised and conducted political education workshops for members of the civics.

On the other side, I was involved in Umkhonto weSizwe’s covert operations in psychological warfare and secret propaganda. Even though I was not thoroughly trained as an MK soldier, I was brought into this group because, ideologically, they appreciated my input. This MK cell had about four of six people in that group who had been students at Wits University, where I had started off as a lecturer. From 1992 to 1994 we lent what I would call unattributable support to the movement (plausible deniablity was key).

The dream was to delink the [South African] economy from Western capitalism, so that we could set up a more or less a bartering system between South Africa and the frontline states; to become self sufficient and that would mean reneging on [the] IMF [International Monetary Fund] and World Bank loans [of] the apartheid government. Number one, this also meant returning the land to Black South Africans. Number two, it meant putting the Reserve Bank into the hands of the ANC when we came to power. It would mean nationalising the banks and nationalising the mines.

Those dreams were squashed by Western intervention and by the moderate wing of the ANC, which became dominant largely due to two macro reasons and events: first, the fall of the Soviet Union and, second, the assassination of Chris Hani and the purging of Winnie Madikizela-Mandela and the “ultra leftists” in the ANC (which included the capitulation of [trade union federation] Cosatu and the [South African Communist Party] Central Committee). It was the external forces of anti-Blackness, but it was also the internal complicity of a moderate section of the ANC that became dominant.

Frank B. Wilderson III’s 7th grade class photograph at Jefferson Jr. High. Minneapolis, Minnesota. (Supplied)

Frank B. Wilderson III’s 7th grade class photograph at Jefferson Jr. High. Minneapolis, Minnesota. (Supplied)

So how did South Africa’s political transition shape your experiences during this period and lead to the inception of Afropessimism?

Well, I began to realise that South Africans suffer from capitalism in very important ways, but they also suffer from anti-Blackness in essential ways. Anti-Blackness is the essential grammar of South African suffering. I really didn’t think of that until years later when I was back in the United States and I was able to look back on what had happened in South Africa in the ’90s.

When I arrived, in 1989, the dollar equalled R2.63. By 1997, the rand had fallen to almost half its value to the dollar. The woman I was married to in South Africa, Kamogelo, said something towards the end of our marriage. She said that the rand’s freefall (which continues to this day) was because the currency was no longer seen as white money — post-’94 it was Blackened in the eyes of the world. I was still a dedicated Marxist, so I offered a purely economic analysis to answer her observation.

What I realised later when I was in US, when I began to work with Saidiya Hartman, David Marriott and Jared Sexton, is that I was thinking about the devaluation of the rand through rational Marxist terms, but that doesn’t work.

Even though the country had not changed the structure of its economic base significantly, the mask of Blackness meant that the world now saw South Africa as a Black space and so the currency experienced one of the constituent elements of social death, which is “general dishonour”. I am still an anticapitalist. I teach Karl Marx’s Das Kapital every year. I am not throwing out the baby with the bath water, but Black people suffer essentially through social death.

In 2002, I was speaking with Saidiya and we did an interview in a journal called Qui Parle, and I was telling her a story about teaching at Khanya College in Johannesburg. I was teaching Ayi Kwei Armah’s The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born to students between the ages of 18 and 25. Remember that these are students who had been politically active members of Cosatu, and members of ANC Youth League. They thought that tomorrow — whenever tomorrow was going to be, in two or three years time — they believed that tomorrow we would be triumphantly rolling down the streets of Pretoria in Soviet tanks having commandeered the entire country.

I was telling them about the day after Kwame Nkrumah was overthrown. The Beautyful Ones Are Not Yet Born is a novel about neocolonialism and its operations through the centres of the civil service. Throughout the novel, what is described is the social death of the people in Ghana and the ways in which we go from colonialism to neocolonialism with a Black face.

The students were very angry with me, because I was saying to them that this is a novel that dramatises Frantz Fanon’s chapter, “The Pitfalls of National Consciousness”. This is a novel that tells you what happens if you don’t push all the way for communism; this is a novel that tells you what happens if you don’t line the apartheid generals against the wall — or at least give them life without parole. ([Fidel] Castro tried to tell this to [Salvador] Allende, who wouldn’t listen — and we know what happened there.)

In a way, this is a novel that tells you what happens when you go through a TRC [Truth and Reconciliation Commission], an unethical exercise in which revolutionaries must atone as well as fascist security officers; then you give Black people the vote without the return of their own land or control of the means of production. It tells you that you will find yourself in a dystopic universe in which Black people are poorer than they were than during colonialism. You get a flag-n-anthem nation where corruption is rife.

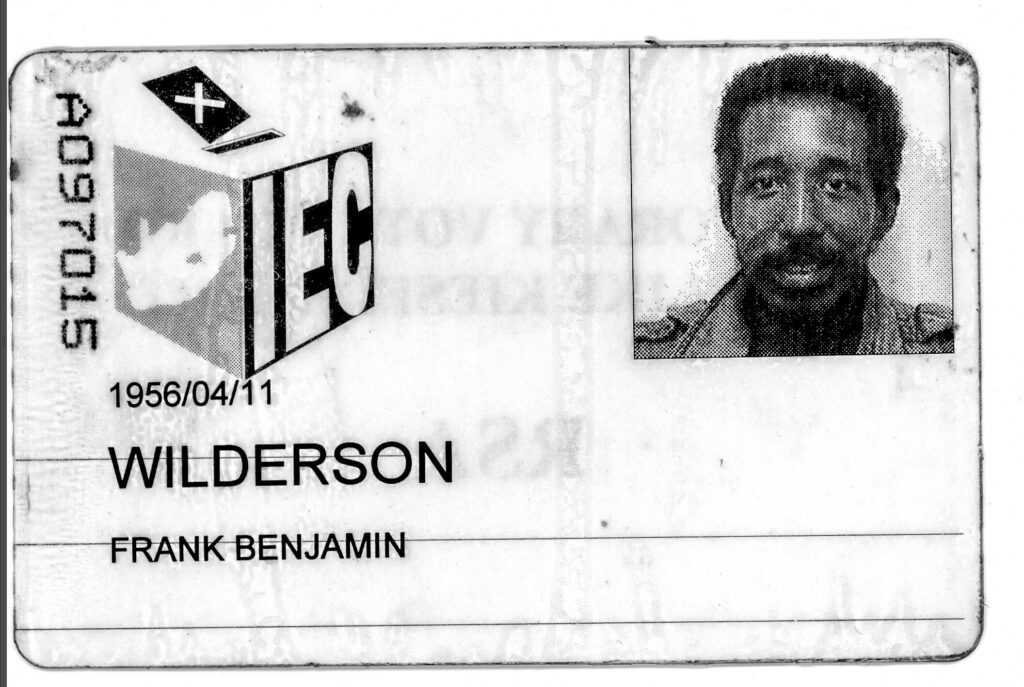

Frank B. Wilderson III’s IEC voting card for South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994. (Supplied)

Frank B. Wilderson III’s IEC voting card for South Africa’s first democratic elections in 1994. (Supplied)

But the students’ rejoinder to me was, “That is West Africa; that is a West African experience, but we in South Africa are going to take all the money from the Oppenheimers. We are going to redistribute the wealth and have a glorious future that does not look like that novel.” I must tell you, Zama, that they were seduced by their rejoinder; I too was seduced by it.

When, in 2002, I recollected this classroom experience to Saidiya Hartman, I told her that Black South Africans have a better psychic space than Black Americans, because they have their genealogy, they have their languages, they have their burial sites and so they don’t suffer the psychic despair that African-Americans suffer from. Saidiya said to me that that is not true. At that time I was a graduate student and she was my adviser. She said to me that she is very suspicious of the idea that the African does not share the same depressive personality as the African-American.

So you had this conversation with her 2002, in the interview in Qui Parle, “The Position of the Unthought”?

Yes, in that interview she gave us the word “Afropessimism” and she began to describe that there are some things that a Black African might have, in terms of cultural accoutrements, such as their languages Ndebele, Xhosa, Zulu, Pedi, Tswana. They may have a genealogy, but at the same time, the hydraulics of social death are suffered by Black Africans in the same paradigmatic way as Black Americans. At that moment when she said that a light bulb went off that took me back to when Kamogelo said the rand fell not because of economic factors but because it was now a Black currency, and I thought, “Aha!”.

I also had to learn that anti-Blackness is a mobilising force inside the Black psyche just as it is a mobilising force inside of the non-Black psyche, which is precisely why there is so much femicide in South Africa now: Black men killing Black women in spectacles of violence that mime anti-Black lynchings. Anti-Blackness cuts through and organises the unconscious of everyone; it just doesn’t benefit Black people when we are deployed as its implements and turn it on ourselves.

This is similar to the violence that we are experiencing in the States against Black trans women, which gets scant attention from most Black politicos. Anti-Blackness is precisely why we can have so much militarised violence targeted at people in townships, even today, when the military and police are largely Black.

It is because, as David Marriott says, the Black psyche is at war with itself; the Black psyche is modelled on the white ideal. In On Black Men he writes, “They cannot love themselves as black but are made to hate themselves as white … What do you do with an unconscious that appears to hate you?”

Could you expand a bit more on where you extracted the ideas that inform Afropessimism? And, for people who may be unfamiliar with the idea, what is Afropessimism?

As I mentioned, Saidiya Hartman offered the term. But you see, I believe that On the Postcolony, regardless of what its author [Achille Mbembe] thinks, makes Afropessimist interventions. There was something happening in the work of Saidiya Hartman; there was something happening in the work of Hortense Spillers, there was something happening in the work of David Marriott and there was something happening in the work of Achille Mbembe, even if he doesn’t want this, and Orlando Patterson.

I wanted to ask myself, “What is connecting the dots between all these works?” It was a theory of violence: a theory that said that the violence that positions Blackness in a paradigm cannot be analogised with the violence that positions other oppressed peoples in a paradigm. Afropessimism is, in my view, first and foremost an analysis of structural violence.

In Slavery and Social Death, Orlando Patterson argues that the violence of any Human paradigm of subjection, for that matter, has a prehistory. It takes an ocean of violence to transpose serfs into workers. It takes an ocean of violence over several hundred years to discipline them to the point where they imagine their lives within new constraints: urbanisation, mechanisation, and certain types of labour practices.

He calls this the “prehistory” of the paradigm’s violence. Then violence recedes and goes into remission, and only comes back at times when capitalism needs to regenerate itself or when the workers transgress the rules and push back (when they withdraw their consent). Afropessimists call this contingent violence.

But the slave, the Black, exists in a paradigm of gratuitous violence — violence that never goes into remission, even when the slave, the Black has shown no signs of transgression. This is because anti-Black violence secures a different paradigmatic division than the division between the worker and the boss. It secures the division between the Human and the Black.

So, the rituals of bodily mutilation and murder are necessary to securing this division as spontaneous consent is to securing the division between workers and capitalists. Capitalism, as a paradigm, needs obedient workers. Social death, as a paradigm, needs the ritualistic spectacles of mutilated and murdered Black flesh.

What this violence produces is the antithesis of the Human and, in so doing, also secures the coherence of what it means to be Human. It reproduces the knowledge that Humans have. This is why we, Afropessimists, believe that the essential antagonism is not between the workers and bosses but between the Humans and the Blacks.

What I mean by that is that in a capitalist paradigm, if you were to show atrocity after atrocity visually through social media and the internet, what you would have is major policy incursions to reform — to bring an end to its gratuitous nature — so that workers would get back to work. We have to ask ourselves why is it that the more violence that happens to Black people, and the more it gets visually recorded and transmitted, the more the violence happens.

It is as though the visual distribution of these images accompanies an increase in their occurrences, not vice-versa. We need to understand that anti-Black violence is not like anything else: these are rituals of pleasure and psychic renewal for the Human race.

As David Marriott would say, these are rituals of self-fashioning; these are repetitions of death in real life and repetitions of death on the screen. They secure subjectivity for non-Blacks, because non-Blacks can look at them and say (albeit if only unconsciously) “aha”, if that were to happen to me, that would be because I committed a transgression; there would be something justifying that treatment. It would not be gratuitous, it would be contingent violence.

Afropessimism helps us to understand that anti-Black violence is not a form of discrimination; anti-Black violence is a health tonic for global civil society. Anti-Black violence is an ensemble of necessary rituals that are performed so that the human race can know itself as Human and not as a slave, meaning not as Black.

Part two and three of this interview will be available online here.