As we attempt to recover from the economic and public-health effects of Covid-19, we must also address one of the great challenges facing South Africa, namely, the future of Eskom. (Rodger Bosch/AFP)

For the past 12 years, the National Energy Regulator of South Africa (Nersa) has been granting Eskom tariff increases of above the consumer price index (CPI).

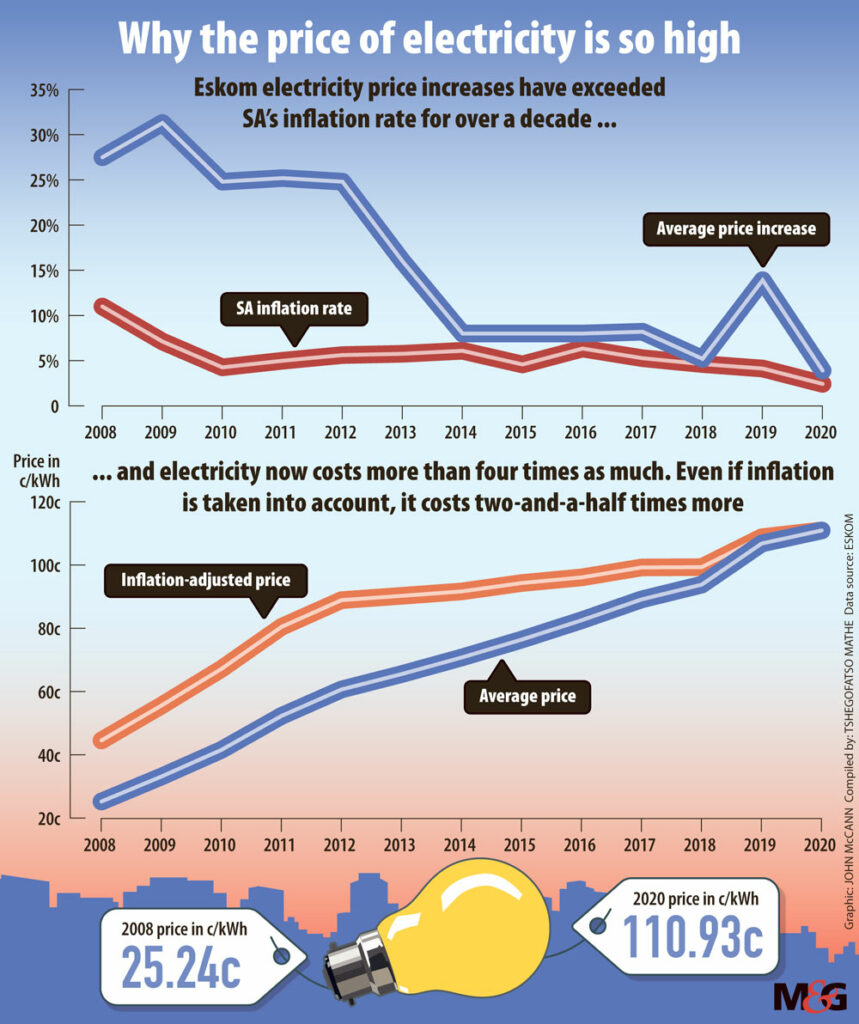

In 2008, the year after load-shedding began, the average electricity price climbed from 19.80 cents to 25.24 c/kWh (cents per kilowatt hour), a hike of 27.5%. The inflation rate was 10.9%.

In 2009, when the annual inflation rate was 7.1%, there was a 31.3% jump.

Before this, the rise in the cost of electricity never exceeded the annual inflation rate.

In 2008 consumers paid about 44.6 c/kWh. Today they are paying 110.9 cents per kilowatt hour.

The constant above-CPI increases bring into focus the role the regulator plays in protecting every consumer who pays for electricity. Nersa’s capacity and capability to fulfil its mandate adequately is now being questioned.

“Eskom is making us poor,” said independent energy expert Ted Blom. “That is what killed this economy.” Adding that tariff increases need to be capped, Blom said Eskom could not “recklessly” spend money and then be allowed to recoup it from consumers. “Where are you going to get extra money to pay for electricity prices that are above CPI?”

This year the national regulator lost a court case against Eskom. This is the first time Nersa and Eskom have taken matters before the courts. The ruling against Nersa was last month at the high court in Johannesburg. Judge Fayeeza Kathree-Setiloane ruled that the regulator was wrong for including a R69-billion equity payment from the government in its calculation of Eskom’s allowable revenue for 2019 to 2022. The R69-billion was allocated to Eskom in the 2019 budget to service the utility’s enormous debt. Nersa has filed for a leave to appeal.

Though the regulator is appealing the ruling, consumers will just have to get ready for another tariff hike that is once again above CPI.

The average standard Eskom tariff will increase from 116.72 c/kWh to 128.24 — an increase of 9.8% — as the first R23-billion is recouped. This will take place in April next year.

This is on top of the 5.22% tariff increase the power utility had already negotiated for next year and will bring the total hike to about 15%.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Tariffs are an important source of revenue for the state-owned power producer, which supplies 95% of the country’s electricity. But the utility has been operating at a loss for years and is struggling to service its R440-billion debt, which it incurred through its salary bill, fuel and debt servicing costs as well as a history of corruption and mismanagement. Eskom is expected to make a loss of R20-billion in this financial year.

Nersa’s regulator member, Nhlanhla Gumede, confirmed that tariffs had been set above CPI, but he attributes this to the national regulator’s outdated method of setting up electricity prices. He is calling for a change in how tariffs are calculated and determined for industry and consumers.

But circular 71 from the treasury states that Nersa must consider the CPI when determining whether the increase in expenditure will be funded by a hike in the revenue base or by some other means.

This is in line with section 3 of the Electricity Regulation Act, which states that a regulator must enable an efficient licensee to recover the full cost of its licensed activities, including a reasonable margin of return.

Gumede seems to agree with the Act, but he does not see Nersa’s tariff increases operating outside the confines of the Act. He instead believes that Nersa still needs to strengthen its “capability” when it comes to considering prices of electricity.

“Nersa’s strategy, unfortunately, needs to be changed. If you have a strategy that is not relevant for the times, it means that your internal processes, your people architecture, even your IT architecture can only be wrong. So that is what we are embarking on. Changing the strategy,” he said. “It’s not about the competency per se, it’s the inappropriate strategy — it encompasses everything.”

In addition to changing how tariffs are calculated, Gumede believes that the recent judgment, which favoured Eskom, could have been avoided if Nersa was “procedurally fairer”. He said the method where Eskom goes to the public to seek comment, and then a decision is made without further discussions with the licensee needs to be changed.

But Makoma Lekalakala, the director of environmental justice organisation Earthlife Africa Johannesburg, said Nersa has for years not been playing a “valuable role” for the consumer. “They have allowed Eskom to get away with too much.”

Lekalakala said the annual increases for a failed energy supplier make no sense, especially since it is becoming more evident that Nersa has lost control of Eskom. Earthlife Africa had made submissions to Nersa every year since 2008, calling for the improved functioning of Eskom in an attempt to curtail the rising tariffs.

Lekalakala added that there was a disturbing level of incompetence at both the energy regulator — which does not seem to understand its role and its responsibilities — and Eskom.

“People are paying more for everything, and this impacts on their quality of life,” she said.

Tshegofatso Mathe is an Adamela Trust business reporter at the M&G