Aerial view of an abalone aquaculture farm on June 9, 2020 in Lianjiang County, Fujian Province of China. (Photo by Tan Ailong/VCG via Getty Images)

Live abalone exporters have a short window to get this “white gold” to their overseas clientele.

“It’s a big portion of the South African abalone industry on the farm side — live exports,” Abagold’s marketing manager Werner Piek said this week.

“And because it is highly perishable, we’ve only got 48 hours from what we call ‘tank to tank’ — from as soon as we take it out of the tank in South Africa to when we must have it in another tank somewhere around the world.”

Getting this done, Piek said, means relying on the slick choreography of shipments, usually using passenger flights. When Covid-19 hit the domestic flights from Cape Town to Johannesburg were cancelled and this dance quickly fell apart.

Abagold, which started its Hermanus-based operation in 1984, could not lose time adapting. Airfreight costs have almost tripled as a result.

And efforts to stop the spread of the coronavirus drove down demand and prices in Asia earlier in the year.

With little indication of when the Covid crisis will subside, investment in abalone farming may cool — a prospect that will threaten attempts to tip the scales in favour of the legal trade and, by extension, save the endangered sea snail from extinction.

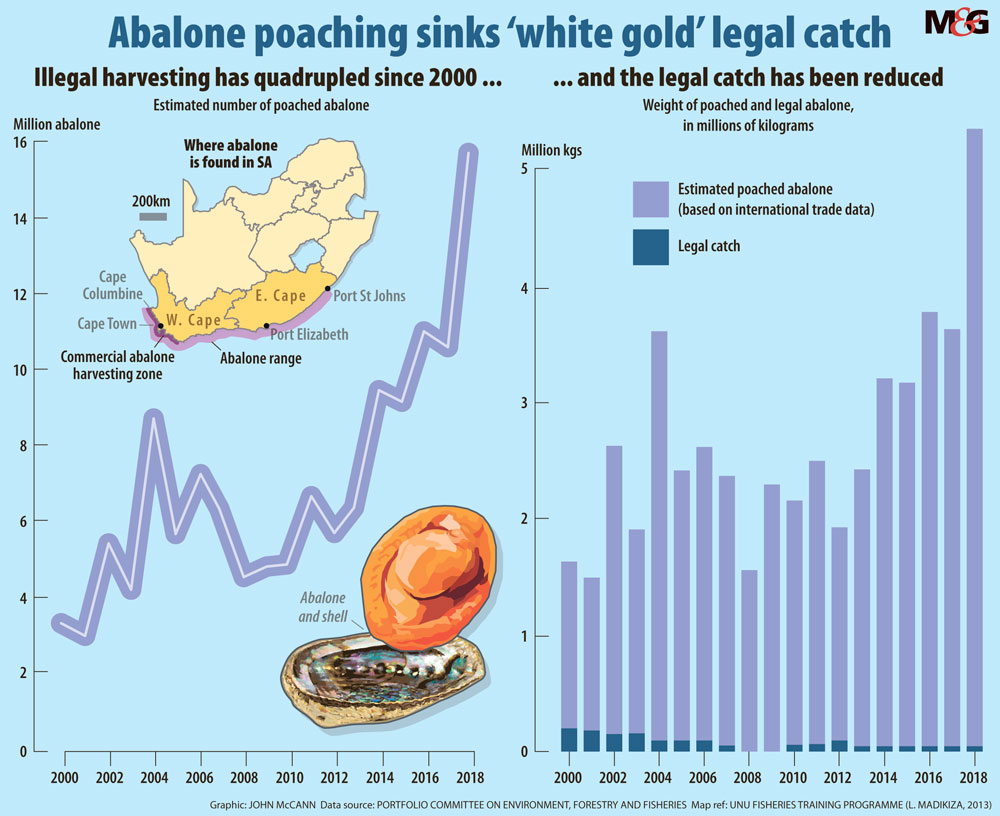

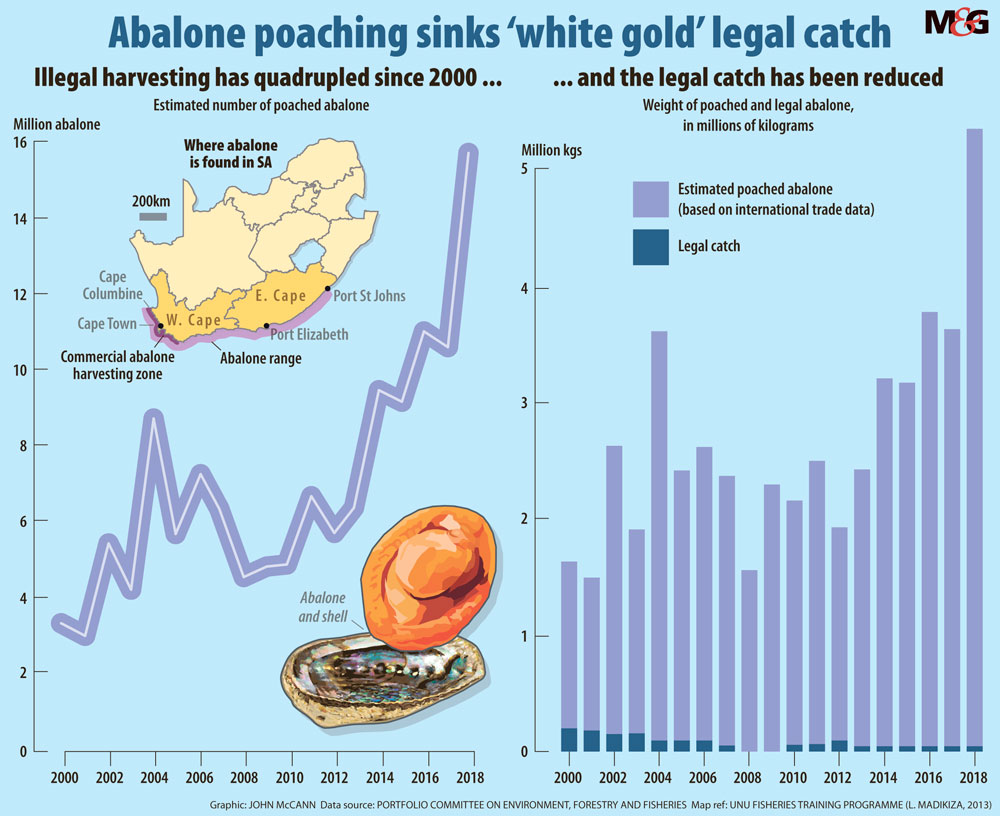

For years, the government has supported the expansion of abalone farming as a way of tapping into the high-value export commodity. On the international market, South Africa is the smallest exporter of legally-sourced wild abalone. On the illegal market, however, it is the biggest exporter.

In a 2016 policy brief, the independent, nonprofit, economic research institution Trade & Industrial Policy Strategies projected that the total value of South Africa’s legal abalone production would rise to more than R2-billion by 2020.

But the illegal trade cost the country R10-billion in 2018, according to a report by Traffic, an international wildlife trade monitoring organisation.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Taking back abalone exports required a greater focus on the country’s youngest agricultural industry. Aquaculture is the farming of marine life, including abalone, which now accounts for 77% of the total value of the industry.

Earlier this year, the department of trade and industry called aquaculture “a future growth sector to be unlocked”. The industry has grown relatively steadily until recently.

The pandemic’s negative effect on legal abalone exports is “complicated”, Piek said.

“The lockdowns in various parts of the world played different roles and had different effects on us. But we became aware of the effect when our first orders were cancelled in the middle of January, when China had the lockdown in Wuhan. This forced us to look for alternatives outside of the mainland China market.”

Hong Kong is one of the biggest markets for abalone exporters. But political upheaval and the significant drop in tourism caused by the pandemic have hit exports hard. “That demand has stayed at a very low level,” Piek said.

Seafood consumption is considerably higher overseas than it is in South Africa. In China, for instance, each person on average consumes about 40kg a year. In South Africa, each person eats between six and eight kilogrammes of seafood a year.

The pandemic hit most farming sectors in South Africa, as the supply to the food services sector internationally and locally was cut off. In June, Peter Britz, chairperson of the Aquaculture Association of Southern Africa, told parliament that the result was a significant bottleneck in supply.

The cost of keeping animals alive was high. In the abalone sector, Britz said, one could pump up to 8.5-million litres of seawater into reservoirs. The electricity alone cost farms about R1.5-million a month.

Abalone has to be harvested every day, so the farm doesn’t run out of space, Piek said. This means the company has had to shift its focus from the food service industry to retail sales.

Live abalone prices, primarily sold to the food service industry, have come down by 30% to 40%.

Piek said he is confident prices will recover once the market reopens. “But it is anyone’s guess when Covid-19 and lockdowns will be over around the world.”

Listed companies have also felt the heat. Irvin & Johnson recorded a 7.2% decline in revenue between July 2019 and 30 June this year. This, according to the financial report of I&J’s parent company, AVI, was mainly the result of a 4.8% decrease in sales volume, and lower foreign currency prices achieved on certain fish products and abalone.

On Monday, Premier Fishing released its most recent set of

financial results, which showed the effect of Covid-19 on abalone exports continued in the second half of the year.

According to the results for the year ending 31 August, sales volumes were higher than the previous year, but prices dropped because of the effect of Covid-19 on the Far East markets. Profits from abalone sales almost halved and revenue from exports to the Far East dropped from R75-million to R58.4-million.

Nigel Dorward, secretary of the Abalone Farmers Association of South Africa, said the Covid-19 shocks to the sector have not subsided. There is still a shortage of airfreight, and demand is still low.

“It has picked up slightly in the last couple of weeks, but prices are still down … and there is no huge light on the horizon. There has been a huge hiatus. In fact, the valuation impact is really only going to be coming through about now.”

He said abalone is a good looking export in theory. But, “there has definitely been a cooling in the appetite for investing in the abalone sector.

“It is an industry in a state of flux,” he added. “There are still a whole lot of unknowns. But by and large, people are getting stuck in and trying to stay alive.”