Despite recording massive drops in their earnings in 2020, South Africa’s largest banks avoided total meltdown.

Despite recording massive drops in their earnings in 2020, South Africa’s largest banks avoided total meltdown. The country’s banking sector is resilient, a fact that allayed early fears they may not be able to withstand the Covid-19 shock to the economy. A banking sector crisis would have a knock-on effect that would send the country’s financial stability into a tailspin.

In its May 2020 edition of the Financial Stability Review, the South African Reserve Bank noted that profits would likely be under strain as a result of the pandemic. A later edition of the review noted that during the lockdown profit declines in the banking sector reached lows previously reported eight years ago.

The review added, however, that South Africa’s biggest banks “hold sufficient capital buffers to withstand a macroeconomic shock of unprecedented severity”.

Resilience was the message in the last two weeks, as some of the country’s biggest banks released their full-year 2020 financial results. This is despite the still treacherous conditions which saw South Africa’s economy shrink by 7% last year.

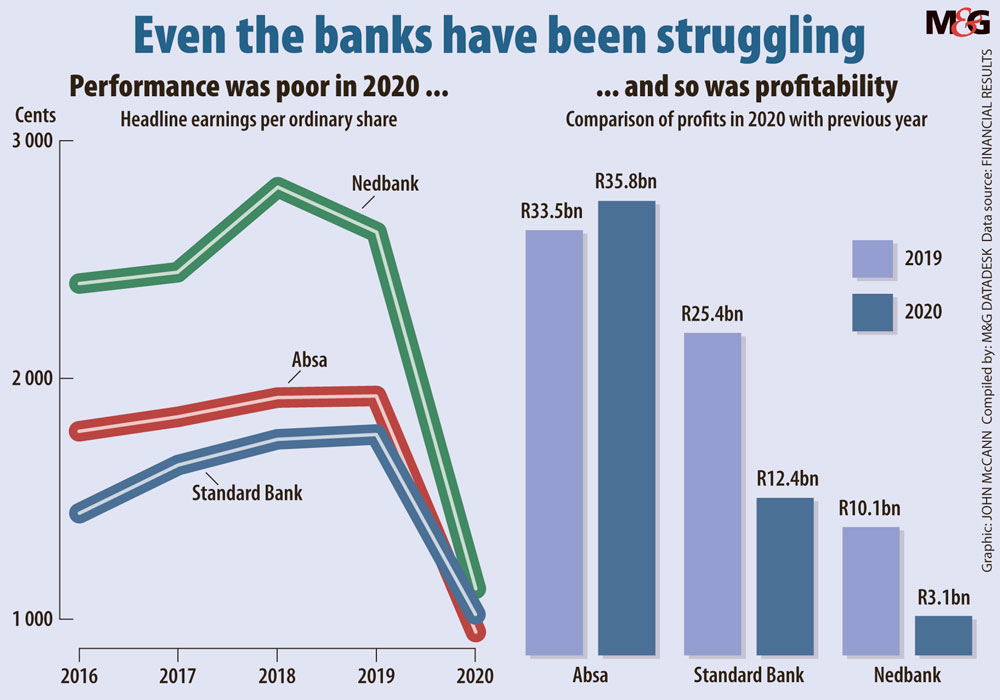

The banking sector was however not spared from the onslaught. Standard Bank, Absa and Nedbank all recorded massive declines in their headline earnings. Earlier this month FNB’s parent company, FirstRand, reported a 21% decline in headline earnings in its interim results for the six months ended on December 31.

The main culprit for declines in earnings were credit impairments, which rose as banks restructured some loans and offered repayment holidays to their struggling clients

As the country’s fourth largest bank, Nedbank’s earnings were the hardest hit, falling 57% compared to 2019.

In his message to shareholders, Nedbank chief executive Mike Brown said that despite unprecedented challenges, the sector and Nedbank “demonstrated strong levels of resilience and was able to support clients while remaining well capitalised, liquid and profitable, albeit at levels lower than in the prior year”.

Despite a strong liquidity position, Nedbank, like Absa, decided not to declare a final dividend for 2020 owing to uncertainty about the progression of the virus and the effectiveness of the vaccine roll-out.

Nedbank’s liquidity coverage ratio (LCR) — which requires banks to hold cash or assets that match or exceed projected cash outflows over a 30-day period — was 126%. This was 11% higher than in the first half of the year.

Last year the reserve bank lowered the regulatory minimum for the LCR from 100% to 80%. This change was aimed at making it possible for banks to continue lending amid expected liquidity shortages and a rise in defaults. The objective of the LCR is to promote the short-term resilience of the liquidity risk profile of banks.

Similarly upbeat sentiments were expressed earlier in the week, when Absa chief executive Daniel Mminele presented the bank’s results. Absa’s LCR was 121% at the end of 2020.

Absa fared better in the second half of the year, Mminele noted on Monday. The bank’s earnings fell by an alarming 82% in the first six months of 2020 but by the end of the year were down by 51%.

Jeremy Gorven, a senior analyst at investment firm Stonehage Fleming, said the suspension of dividends and the fact the banks remained profitable helped them through 2020. Standard Bank and FirstRand have recently decided to declare dividends following better than expected results.

The average return on equity for the 2020 financial year was 6.9%, Gorven noted. “So that’s much lower than it usually is. But it is still positive, which means without paying dividends, banks are adding to their capital.”

Gorven added that the recovery of economic activity in the second half of 2020 and slower growth in credit losses have helped the banks rebound.

“So in general the outlook is positive for profit growth and returns. But that doesn’t mean the banks will be earning the same returns pre-pandemic. What we will see is uneven recovery and it may take some time.”

Conrad Beyers, the Absa chair in actuarial science at the University of Pretoria, said the results from the banks are much better than was feared when the pandemic hit. The university has conducted high-level stress testing of South Africa’s largest banks.

“One should of course add that banks are still in a very tough and uncertain position,” Beyers added.

But, he added that the expectations had been “really bad”.

“There might have been a possibility of a crisis. So currently those expectations have not been realised,” he said.

“It does not mean it is a rosy picture, or really positive. They lost a lot on credit impairments, which is extremely bad … But at least it appears that the banking system is going to survive — at least for now.”

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

New law to prevent future crisis domino effect

New legislation for the financial sector will help stop the “doom loop” that happens when big institutions fail during a crisis. This is according to treasury deputy director general Ismail Momoniat who, during parliament’s finance standing committee on Tuesday, explained a banking crisis “impacts on your sovereign risk and it impacts on the fiscus and it creates an economic crisis”.

The treasury was in parliament for a presentation on the Financial Sector Laws Amendment Bill, which is aimed at bolstering financial stability in the country. Part of the Twin Peaks reform of the financial regulatory system, the bill introduces regulations to deal with failing banks.

The cabinet approved the tabling of the bill last June. The bill will minimise the use of public funds as a default source to bail out failing banks and other large financial institutions. Major banks will also have to plan for the possibility of their failure.

In its presentation, the treasury noted that banking crises have historically contributed to large increases in public debt.

“For that reason, you find that governments are forced to come in — it’s almost like having a gun to your head — if you don’t it is going to be a worse crisis … And generally financial crises, if they are the cause of a recession, it takes much longer for the economy to get back to recovery,” Momoniat said.

Banks pose a significant risk to the economy, the treasury said. When one major bank fails, there tends to be a domino effect on a number of connected institutions.

“What we don’t like is that when there are profits to be made, they obviously go to the shareholders of the bank … But when a major bank is in trouble, when there are losses, then society has to take the cost,” Momoniat said.

“And that is the problem we are trying to deal with and prevent.”