The Texture of Silence, featuring Cara Stacey, Keenan Ahrends and Mzwandile Buthelezi, explores composition, improvisation and the grey area in between. (Supplied)

The more I think about it, the more the National Arts Festival description of Standard Bank Young Artist for Jazz, saxophonist and composer Sisonke Xonti, as the “new face of South African jazz — urban, erudite, skilled but rooted in his culture”, disturbs me. He is all those things, for sure, as his second festival performance ably demonstrated.

Sisonke Xonti, the Standard Bank Young Artist for jazz, brought a fresh perspective to sounds from around the country. (Supplied)

Sisonke Xonti, the Standard Bank Young Artist for jazz, brought a fresh perspective to sounds from around the country. (Supplied)

But so are Tete Mbambisa and Louis Moholo-Moholo, at least a generation earlier. So were the late Dudu Pukwana, Johnny Mekoa and many more. Perhaps “erudite” is code for “he went to university” (so did Mekoa, but plenty of other brilliant players didn’t). I’m not sure what “urban” might be code for, and “skilled but …” carries a most unfortunate implication that we might expect others rooted in their culture to be unskilled. It’s a tough life, writing PR blurbs. There are, after all, only so many words in the dictionary. These need a rethink.

Happily, Xonti is in truth the next generation of our long-established, distinctive jazz tradition: born in the cities, intensely schooled — whether the university was the University of Cape Town or Monde’s Place — and always with a keen ear for intriguing sounds, from grandmother’s knee or the outer constellations.

Xonti’s four-movement Migration Suite served as a beautiful sonic riposte. In it, he’s “trying to make sense”, he says, “of the different sounds I hear around the country.” What the music spoke of was made all the more poignant by our current situation, which hits migrants hardest of all, and that was underlined by Xonti’s fluid, characterful playing —from roots abstraction to compelling swing — as well as by Tebo Moleko’s words: “Should I go home or continue? … [facing] permanent impermanent residencies in the cities of their birth …”

All four movements sing journeys and identity, from the galloping rhythms of the Eastern Cape to the rolling bluesiness of the final movement: the kind of classic melody that might have found a welcome at The Pelican or on the As-Shams label in the 1970s. But all fresh, all original.

Xonti was in good company, from the august presence of percussion master Tlale Makhene, trumpeter Sakhile Simani and pianist Yonela Mnana to bassist Benjamin Jephta and drummer S’phelelo Mazibuko. As he showed in his own set, Simani can be sharp-edged and adventurous, or bate the blades of his notes into gentleness. Mnana’s performance throughout was quite remarkable, whether in the twisty arpeggios of the suite, or when his voice dropped us into territory just south of the Jazz Ministers in the closer, a beautifully extended Nomalungelo. Everything we heard should form the core of a next, must-have album.

‘The Texture of Silence’

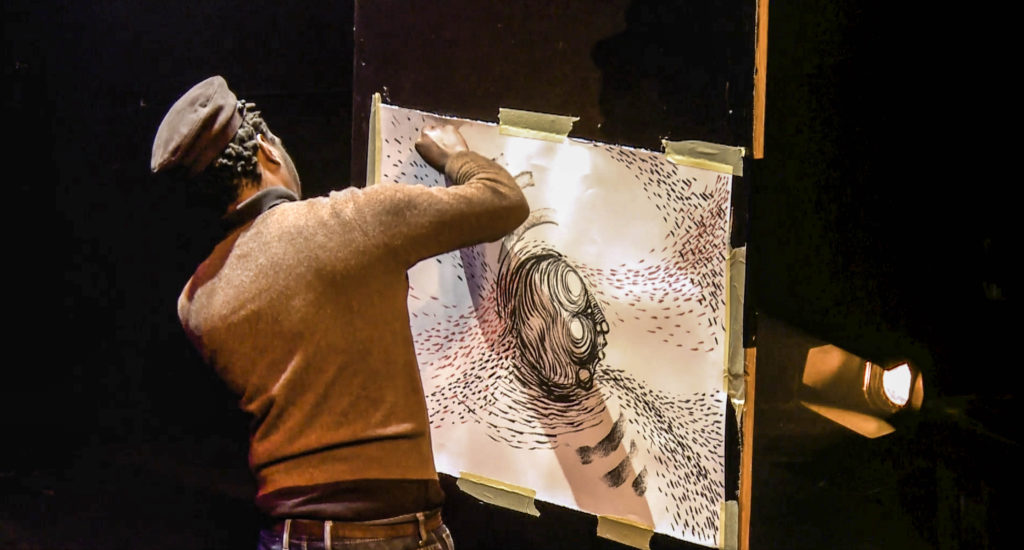

Although the Cara Stacey/Keenan Ahrends/Mzwandile Buthelezi project The Texture of Silence was very different, it was also seeking home: a place where image and sound could both live. Stacey describes its goal as “to create fixed compositions, structured improvisations and free improvisations that help us to explore together”, investigating “the potential and limitations around the terms ‘improvisation’ and ‘composition’ and the grey area sometimes between these.”

Mzwandile Buthelezi paints to the music of Cara Stacey and Keenan Ahrends during a performance at the National Arts Festival (Supplied)

Mzwandile Buthelezi paints to the music of Cara Stacey and Keenan Ahrends during a performance at the National Arts Festival (Supplied)

I’d love to see this project a few months down the line, because there was a sense the three are still learning one another and there’s much more yet to unfold. A wonderful sense of shared and shifting leadership characterised the sounds, as Stacey moved from the metal keys of the nyungwe-nyungwe (thumb piano) to the ivories of the piano, to umtshingo pipe, to umhrube bow, and Ahrends from weaving textures to crafting interlocked pulses and drawing out melodies. Close your eyes and it was still lovely to hear.

On the other side of the stage, a small shower of raindrop-notes on Buthelezi’s paper resolved into the journeys of sound and the face of a creator. At the 40-minute conclusion, I wanted to see more of where it would all go and how the more explicit images emerging on the paper might further provoke the sounds. As they say, watch this space …

Strength and imagination

Tshepang Ramoba (whom you may know as the BLK JKS drummer) explicitly called his project Mošate: home in Sepedi. Inspired by that tradition, but employing contemporary vocal effects and the synthesiser of “Dejot” (Daniel Jakob) in Bern, the music again challenged the “roots” box some festival publicity seems to assume.

Tshepang Ramoba performs with the Blk Jks at the SA Rolling Stone launch party on December 1, 2011 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images /City Press/Leon Sadiki)

Tshepang Ramoba performs with the Blk Jks at the SA Rolling Stone launch party on December 1, 2011 in Johannesburg, South Africa. (Photo by Gallo Images /City Press/Leon Sadiki)

The guitar of Sibusile Xaba as usual played the Sun Ra role (although communities, years and miles distant from the American). It was often he who provoked the rest of the team (sensitive bassist Xola Kulati, trumpeter Tebogo Seitei and percussionist Machume Zango, playing from his Mozambique base, but melding seamlessly into the collective) into space travel.

There’s a wonderful moment of collective abstraction about 15 minutes in that, alone, is worth the ticket. Ramoba has an impressive vocal range, up into an eerie falsetto. Although it was Xaba’s name that had drawn me to the show in the first place, I ended up appreciating the whole ensemble and concept for its strength and imagination. (But the trumpet was under-miked.)

For musicians improvising together on stage, there’s always another home too: the home found in familiar and empathetic colleagues. In 2019, Dutch reedman Mete Erker and pianist Jeroen van Vliet marked 20 years of working together, and their live set, almost the last of the Makhanda jazz events, enacted that almost without the need for words (although, never fear, the Dutch announcements are helpfully subtitled).

Much of the material was from the album, Pluis, which the duo released to mark their anniversary. The title track conveyed the quality of that kind of musical home: each player can take risks because the other has his back. Still, the tune that really caught my ears was Erker’s bright, inventive Dandelion. The Dutch audience was warm, but far too polite — if van Vliet and Erker had actually been in Makhanda, we’d have been stamping.

This article was first published on sisgwenjazz.wordpress.com. It forms part of a series of National Arts Festival music reviews