Photographer and filmmaker Anthony Bila captures a subway trip in New York, 2019

Colourless Green Ideas Sleep Furiously, Phumlani Pikoli’s documentary of his agemates’ exploits in the often intersecting worlds of film and photography, probably won’t be up your alley. It’s a belligerent, mangled piece of work whose redeeming quality is that it chooses well in terms of subject matter.

Featuring the photography and film work of new-schoolers like Neo Baepi, Khulekani Mayisa, Anthony Bila, Andiswa Mkosi and Tseliso Monaheng, it’s an ode to finding one’s way delivered in gratuitous amounts of splitscreen and glitch effects.

The 30-minute film also features loads of brisk edits, meaning the speakers barely get time to finish their thoughts before we jump onto the next one, or we’re hit dead in the gut by the sheer beauty of a photograph, or one of Mayisa’s colour-coded, gently polemical short films. It’s a punky, brash paean to a new generation of documentarians delivered by an insider still in search of a style, making it seem like a secret lockdown gathering, which, in a way, it was.

Featuring online interviews with the above mentioned artists, Pikoli, thankfully, works away from that pallid Zoom aesthetic we have become accustomed to, improvising a path towards something more alive.

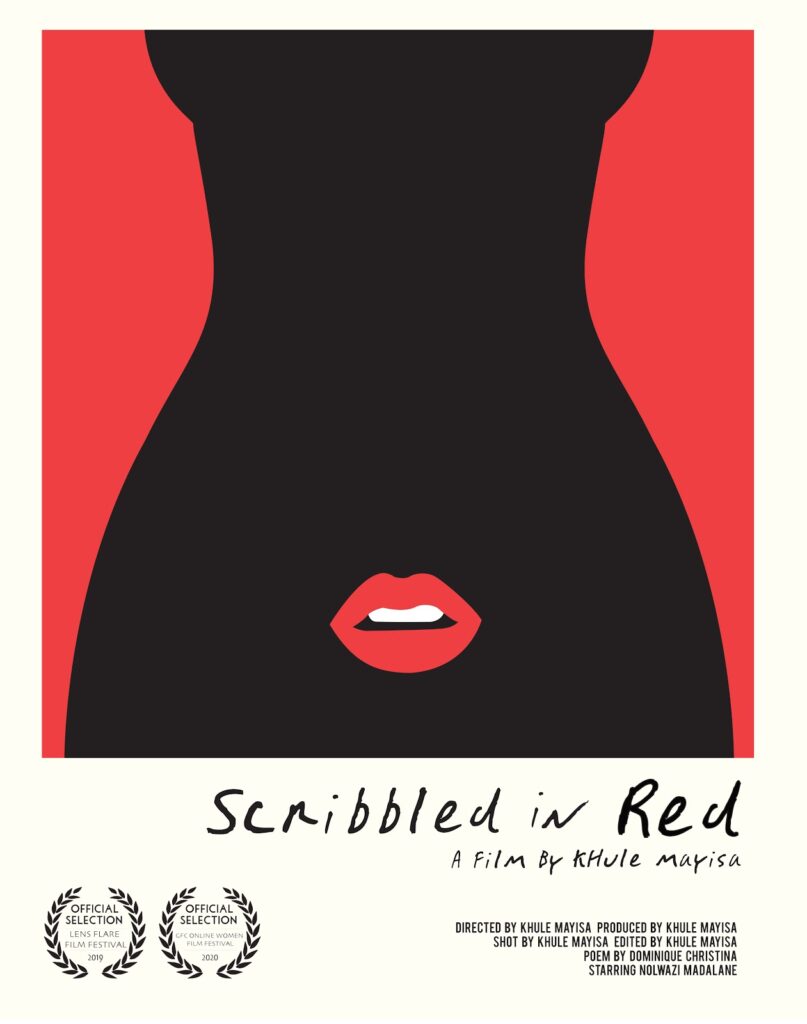

For the uninitiated, the film is also Mayisa’s coming out party, with her short films Scribbled in Red and Power to the Purple more or less bookending the doccie, softening its edges with her beguiling, collaborative feminist manifestos. The Mail & Guardian spoke to Pikoli about the art of autodidacticism.

The poster for Khulekani Mayisa’s short film Scribbled in Red

The poster for Khulekani Mayisa’s short film Scribbled in Red

The other day, I was speaking to some of the people interviewed in your film. One of them said your aversion to fully formed things is something of a defence mechanism: seeing that you did your time in media institutions early on, you tend to avoid structure. But the style itself, they said, still needs to be honed. Can you tell who that is?

Was that Tseliso? He’s the only one near enough to make that kind of analysis, and he’s probably the only person to take my work seriously enough to critique it. Right now, in terms of making stuff, I think he’s got it [down] quite nicely. I struggle with the concept of having things too structured or typically structured. I want to make stuff that challenges motherfuckers to pay attention.

The idea for me is that we come from lowbrow art-making, really. So for me, it’s just about playing and not refining it to a point where it looks like you couldn’t make it yourself. I like the DIY aesthetic very much. The whole film is about access and how people found access.

Why discuss access? Is that an end goal in itself or were you using that to unlock something else?

It’s all about access to resources. For black heads, finding things like cameras … I was keen to find out: Where do you begin with that? Being a storyteller, you could be limited in the way you can tell stories because of resources. When I was listening to that Spike Jonze episode [on the Nine Club], I was thinking it must be so nice to have equipment early on, so in your early twenties you are already getting jobs that allow you to make it into the industry and create a culture that is in your own voice. Outside of access, how does one come to find their own voice?

How widely had you cast your net, initially?

I think I approached two or three other people; they never really got back to me. The people who responded with positive intentions of speaking to me are the ones who I decided to include. Some people trailed off.

What is it about them as a collective that’s interesting to you?

They are all, to some degree, autodidacts. That, to me, is forever interesting because I am one. In terms of writing, I don’t have any real formal training outside of, like, dropping out of varsity and doing internships at publications forever. The same with video and video editing, I learnt on the fly. That shows in the work …

What’s really cool is how each of their personalities come through in each of their work. The way they speak about intention comes off. I don’t know whether intentionality is front of mind all the time. I think sometimes people make work and it’s an organic expression of themselves. The really cool part about everybody’s work is that it shows who they are. A lot of artists try to hide behind their work, whereas with them, their work shows who they are as people.

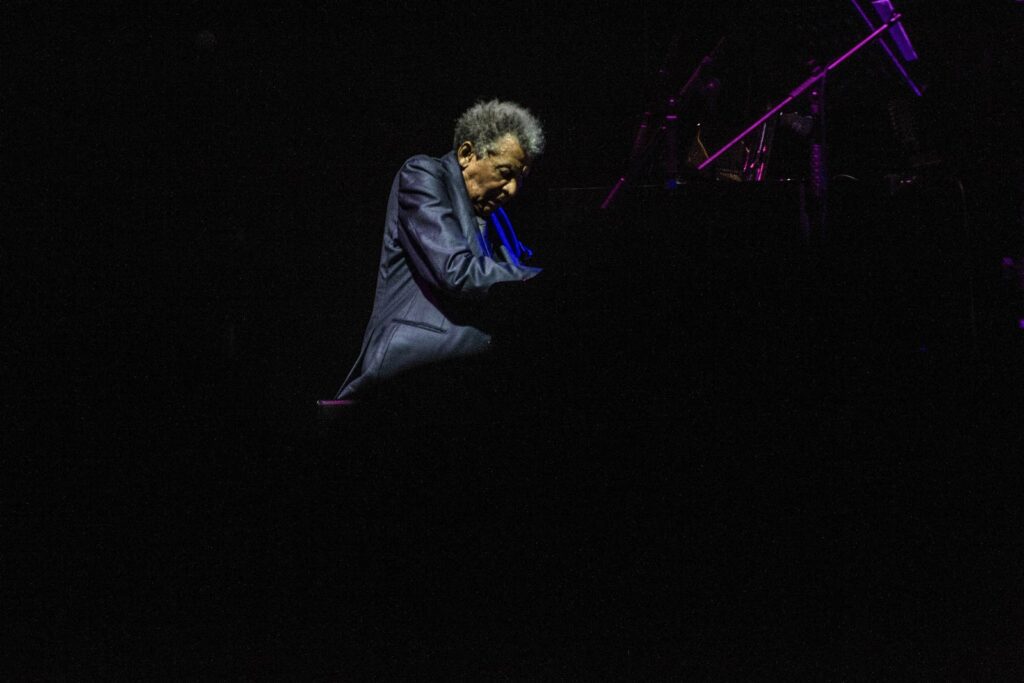

Abdullah Ibrahim, through Neo Baepi’s lens, Johannesburg, 2017

Abdullah Ibrahim, through Neo Baepi’s lens, Johannesburg, 2017

Why is Spike Jonze and the Nine Club podcast episode he features in such an important reference in your work?

Skate culture, rap music — counterculture in itself — is so important and front of mind for my own development and my own artistic appreciation. It’s another example of people being autodidacts. You just approach it, you fall in love with it and you have to develop your own style. You have to pick up pieces and put them together in ways that make sense to you.

When I was listening to Spike Jonze, he said something that woke me up to it. I’ve been holding on to this line since I heard it. They asked him, like “Yo dude, you do all these different things all the fucking time, you never went to school for them. One minute you’re making a movie, the next minute you’re making a skate video, the next minute you’re doing a light show. Next minute you’re doing a theatre performance, the next minute you’re doing choreography and dance — how does any of this make sense?” His response was, “I feel something, then I look for the best medium to express that.” That, for me was like, super, super on the nose because there’s always this accusation of ‘“Jack of all trades, master of none.”

Cool. That’s fine if you’re a purist but I’ve always been interested in many things since childhood. I had a huge fascination with history, I’ve always written, and I enjoyed skateboarding, doing sport and rapping. There’s always a different way to approach something.

It’s about indulging different sides of yourself. When you start skateboarding, you see the world completely differently. People see stairs, wheelchair ramps, rails. We see an opportunity to create something in that moment with that thing and use it in a fucking different way. As a skateboarder, you walk around with a lens of, “Oh shit, what can I do at that?”

A portrait of visual artist Tshepiso Moropa at her home in Johannesburg. (Andy Mkosi)

A portrait of visual artist Tshepiso Moropa at her home in Johannesburg. (Andy Mkosi)

Although you discuss finding a voice, you kind of leave the analysis of style to the viewer.

There needs to be space for the audience to explore and discover. As an audience, we are constantly being spoonfed. I’m interested in igniting interest in their works without giving away too much of who they are. This is more of an introduction as opposed to spoonfeeding. I’ve gotten frustrated with this state of a lack of subtlety that we live in.

One of the interesting things about getting into the internet early was falling down rabbit holes and discovering people’s work in ways you could resonate with — and, from there, finding links to other people. Like who else is fucking fly. It was also a challenge to the viewer to find things they were interested in.

The Colourless Green Ideas Sleep Furiously can be viewed here.

This article is part of a partnership between the Mail & Guardian and the Goethe-Institut, which focuses on innovation in all its aspects.