Hussein Salim’s, Ante- chamber, 2020, typifies his style, which leans towards abstraction and was nurtured by an absence of visual references. (Courtesy Melrose Gallery)

Very little has been written about the artist Hussein Salim. It is surprising given he has been exhibiting frequently in South Africa, his artworks sell out at art fairs and in London-based auctions and they present a unique abstract aesthetic.

The fifty-something Sudanese artist attributes the paucity of texts about him to his terrible grasp of English. He has shied away from interviews. In truth, the unique turn of phrases he utters and his economy of language in relaying the essence of his life journey — there are no spare words for idle chatter — add to his charm and make his story more compelling.

In some ways it is a familiar story. Far too many African artists have had to leave their native countries to become and remain artists. However, the way in which Salim has found success and acceptance in a country with a reputation for xenophobia — largely targeted at African nationals — is refreshing. Uplifting even.

His largest solo exhibition in South Africa, The Garden of Carnal Delights, which opened at the Melrose Gallery in Johannesburg last week, presents a landmark of sorts. It is the culmination of a series of fortuitous twists and turns since he left his home town in Sudan in the late nineties.

On paper Salim was not in any way destined to be an artist. Born into a poor family of 13 children, there was pressure on him to pursue a stable income and career.

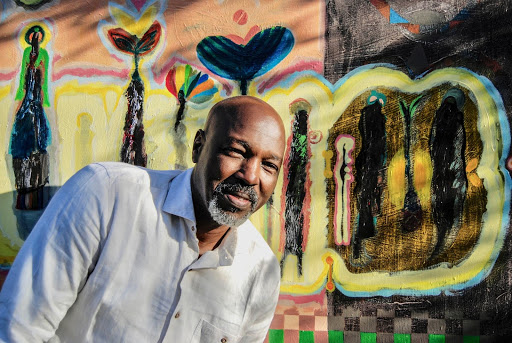

Hussein Salim says the journey of an artist is to find his place in the world. Salim’s place is currently in South Africa. (Picture by Clint Strydom)

Hussein Salim says the journey of an artist is to find his place in the world. Salim’s place is currently in South Africa. (Picture by Clint Strydom)

“It was a day of big conflict in my home,” recalls Salim of the occasion he revealed his ambitions to be an artist to his father.

“You are kidding,” was his father’s response.

Convincing his father that he had a talent worth pursuing was just one of the barriers. There was also the fact that the rural village of Karim, where he grew up, was an actual desert — and a cultural one too. There was no access to books, images or art. The internet had not arrived either. It seems almost impossible that someone would grow up aspiring to be an artist in such a context, but, conversely it seems to have shaped Salim’s proclivity for images.

“I grew up surrounded by emptiness. Total emptiness. I never saw an apple until I was seven years old. I knew they existed but didn’t know what it might look like. Is it square? Does it have stripes? That kind of emptiness and poorness allows us to imagine things because we don’t have it in front of our eyes,” says Salim.

Not only did this absence of visual references feed his imagination and desire to draw but it also set him on a path of abstraction that has marked his art ever since.

Orack, 2020. (Courtesy Melrose Gallery)

Orack, 2020. (Courtesy Melrose Gallery)There is a vast range of works at The Garden of Carnal Delights, in different palettes and marked by varying abstract patterns. In Ducklings, all manner of motifs recalling letters of the alphabet, animals, fish and wheels swirl around a leaning figure and two orbs. This should make for a chaotic scene yet all the objects somehow are suspended in a balanced composition.

A work titled Francis is delivered through a much more muted palette of pinks and pale blues, which suits the layer upon layer of details, patterns upon patterns.

This large body of work is all more or less united by Salim’s distinctive language, which remains abstract, though the shadows of human figures keep them somehow grounded in a hazy landscape. He has never painted a traditional landscape.

“I never saw a tree or river until I was much older. That is why I started with abstraction.”

His proclivity for abstraction proved somewhat of a challenge for the lecturers at the University of Sudan in Khartoum, where he studied fine art.

“In a traditional education you begin with figurative works and then you can start to make abstract works.”

Shift 2, 2020. (Courtesy Melrose Gallery)

Shift 2, 2020. (Courtesy Melrose Gallery)The other battle Salim had on his hands was a financial one. To remain in art school and buy materials he had to sell his art straight away. He discovered pretty quickly that the Sudanese do not value art.

“To be an artist in Sudan is a sin — is a social sin, a mistake. I mean it. We had a fundamental Islamic regime holding the power and marry that with a bad economic situation. We had a good school of arts but it is being demolished day by day. That place is seen as the devil’s place in the fundamentalist regime mindset,” he observes.

It was in the staff of foreign embassies that Salim found what he describes as “an army of good people supporting my journey.”

One of these clients was the conduit who led a German art dealer to Salim’s home in search of his art. The result of this connection was a touring exhibition in Germany in the late 1990s.

Salim never returned to Sudan, save for brief visits. This wasn’t only due to more promising opportunities elsewhere but also due to a deep and painful recognition that his art would never be appreciated in his homeland. This message was driven home in the year of his graduation, when he held a small exhibition at the Hilton hotel in Khartoum.

Garden of Carnal Delights, 2020. (Courtesy Melrose Gallery)

Garden of Carnal Delights, 2020. (Courtesy Melrose Gallery)Much to his surprise the serving prime minister at that time of Sudan was holding talks with foreign businessmen in the hotel. Thinking this might be an opportunity to secure a patron from the highest echelons he connived a meeting with the leader in the corridor where his art was hanging.

“He looked at the price tag and he asked me why it was so expensive. I was shocked. The Turkish guy standing behind him bought that work. I realised then that people out of my country appreciate my art.”

This painful realisation saw Salim embrace a peripatetic existence, largely moving around Europe — Germany, the UK, Belgium and Norway — exhibiting and selling his art. He wanted, however, to settle in an English-speaking country with warm weather.

Australia was first on his list but a long wait in Cairo to secure a meeting for a visa made him consider South Africa. He knew he had made the right choice when the woman at the visa office waived the fees and warmly welcomed him to the country.

He has been settled in Pietermaritzburg with his family since 2004. It has taken time for his art to circulate and gain attention but he has been carried by committed collectors in this country since his arrival.

“South Africans have a unique taste in art. This might be due to its complex history. They know how to collect art and when you put something new in front of them they recognise it immediately. In one year I did better here than 10 years in Europe,” he says.

Interlude II, 2020. (Courtesy Melrose Gallery)

Interlude II, 2020. (Courtesy Melrose Gallery)

The most profound influence on his work came from an encounter at a Jewish primary school he visited in Germany. He was struck by the children’s acute awareness to survive and be accepted in the world.

“This is [like] the journey of the artist. [He] like the Jewish child feels that he is standing against the wind,” says Salim.

Being an artist is intrinsically going to be tied to a narrative of survival and “finding your place in the world,” says Salim.

Salim has found that place via an aesthetic defined by the multitude of cultures he has encountered through his wanderings in Europe. This has been married through a vibrant palette and filtered through layers of patterns, shapes and motifs that are drawn from different cultures.

Perhaps it is South Africans’ desire for a multicultural utopia that allows his art to resonate here. Or perhaps it is his ability to imagine a world beyond what the naked eye can see. – African Art Features Agency funded by the National Arts Council in South Africa

The Garden of Cardinal Delights will show at the Melrose Gallery until the end of May