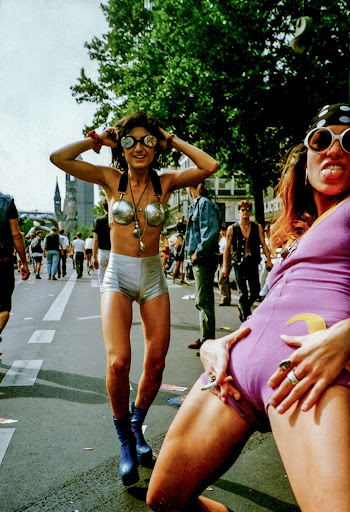

Revellers at The Love Parade festival, Berlin, 1994. (Tilman Brembs/zeitmaschine.org)

1960 to 1979: All back to zero

The East German government leadership wasn’t entirely wrong when they discerned “nihilism” (that is, a rejection of the established societal order) in aspects of Western culture in the late 1960s and early 1970s. At that time, many young West Germans realised that so-called de-Nazification — the removal of Nazi functionaries from politics, culture, the business world, and administration — hadn’t been particularly successful. In many places, the same people held the same positions of power as they did under the Nazi regime — and these people were often the youth’s own parents and grandparents.

For this reason, a part of the younger population rejected the West German value system completely. Many revolted against earlier generations, became involved in leftist and radical leftist groups, and experimented with new forms of communal living. They longed for a new beginning, free of the gruesome past. And this found expression in their music.

Many German musicians were looking for alternatives to capitalist mainstream music, as embodied by blues and rock from the US. They came to create, for the most part without entirely being aware of it, the first genuinely German forms of pop music: “a music that grew out of the cultural ‘nothingness’ that young Germans felt in light of Germany’s role in World War II”, as noted by Stuart Baker and Adrian Self in the liner notes to the compilation Deutsche Elektronische Musik (2010).

Because of Germany’s connection to the West and the US, British, and French soldiers stationed in the country, musicians wavered between an emotional link to such genres as jazz or beat, and radical rejection of this music because they opposed the ongoing war in Vietnam or capitalism in general.

Some wanted to destroy all the old rules and structures; do away with old traditions and conventions, whether it be the division of songs into verse and refrain, the idea that in every band a percussionist must play the same standard jazz drum kit — or the obligatory hierarchy of singer, guitarist, bassist, drummer, with each fulfilling a specific role.

Instead, some German musicians began to use all their instruments without any clear distinctions to create rhythm. They experimented with raw, basic anti-musical ideas. Fascinated by the powerful, expressive potential of sound, people without any training began playing instruments — as would be the case a decade later with punk.

Some began using the compact synthesisers that suddenly appeared on the market relatively inexpensively, not as extra ornaments for the fixed structures of rock music, as was the case in the 1960s, but to invent adequate new forms.

Initially emerging as an underground event in 1989, The Love Parade was largely soundtracked by trance, house and techno. (Photo: Tilman Brembs/zeitmaschine.org)

Initially emerging as an underground event in 1989, The Love Parade was largely soundtracked by trance, house and techno. (Photo: Tilman Brembs/zeitmaschine.org)

Not everyone in this scene was a non-musician. Some came upon experimental approaches by way of their conventional musical training, studying for example under the composer Karlheinz Stockhausen or attending the workshops for improvised electronic music held by the contemporary composer Thomas Kessler in Berlin.

The result was that in the late 1960s and early 1970s, an avant-garde, non-blues-based, structurally open form of psychedelic rock emerged in Germany. This form was called by the British press, at first disparagingly, “krautrock”, a term derived from the pejorative term used for Germans in World War II: “kraut”.

Some people involved in the scene embraced this label, others spoke of “cosmic music” — above all, they desired to project themselves into outer space with their synthesisers. Moreover, the general term “psychedelic rock” was used when drug-induced psychedelic elements were added to more traditional rock forms.

These experiments flourished, above all in illegally occupied houses and alternative art and living projects in Berlin, where many artists and outsiders came to escape the booming post-war economy-induced consumption craze and pressure to perform. Ton Steine Scherben may have provided the soundtrack of the occupied house scene, but the more stylistically conservative brand of rock that this band began to play in 1970 is not aesthetically relevant for the developments described here.

Those involved in illegal house occupations didn’t just listen to such conventional rock. In 1969, for instance, a band that called itself Agitation, later Agitation Free, played at the model alternative project Kommune 1. The jam band-like formation produced a free-spirited, flowing ethnic space rock. Among its members was the musician Christopher Franke, who named contemporary composers such as György Ligeti and Stockhausen as his influences, and who would soon leave the band to join the considerably more successful synthesiser pioneers, Tangerine Dream.

From a contemporary perspective, the most musically interesting apparition from this early closely interknit Berlin scene is Conrad Schnitzler, who was born in 1937. He had studied under Joseph Beuys and internalised this artist’s famous doctrine: “Everyone is an artist”. In Berlin’s free cultural spaces, he saw his chance to convert the phrase into musical practice. Not only was Schnitzler the founder of the underground club Zodiak Free Arts Lab (thus creating a breeding ground for the entire Berlin krautrock and cosmic music scene), but also, at a very early stage, he began to play improvised synthesiser concerts.

Among the instruments he used was a self-built “cassette organ”, which could play (kind of) proto samples on eight different cassette players. Schnitzler recorded sounds from Berlin to use as samples, integrating the city itself into his music. Beginning in the early 1970s he released hundreds of albums in limited editions on different labels.

The synthpop piece Auf dem schwarzen Kanal [On the Black Channel], released as an EP in 1980 by the major label RCA, was the most notable of these recordings. Monotone dissonances and Kraftwerk-like synthesisers flash and flicker over a stoically steadfast computer rhythm, while an electronically distorted voice recites Dadaist poetry. More than 30 years later, the cold, alienated machine aesthetic of this three-minute-and-13-second piece still fascinates listeners.

Conrad Schnitzler, who studied under seminal German artist Joseph Beuys, was a pivotal figure in the krautrock scene. (Photo: Mueller Schneck)

Conrad Schnitzler, who studied under seminal German artist Joseph Beuys, was a pivotal figure in the krautrock scene. (Photo: Mueller Schneck)

Schnitzler was also involved, in a less prominent capacity, in several other influential projects. Together with the musicians Hans-Joachim Roedelius and Dieter Moebius, Schnitzler founded the krautrock band Kluster, which after his prompt departure renamed itself Cluster. In Schnitzler’s Zodiak Free Arts Lab club, the hippie jazz collective Eruption came together. This group included three musicians — Klaus Schulze, Manuel Göttsching, and Edgar Froese — who would later all re-emerge in other contexts.

In general, almost all the bands and music projects in this small, experimental scene in Berlin were interrelated: in the cramped island city they were continually exchanging members, while churning out one record after the next. For all its rambling instrumental jams and endless sound surfaces, the music of Agitation Free, Tangerine Dream, Klaus Schulze, Cluster/Kluster and (for the most part) Conrad Schnitzler is rhythmically generally quite reserved — this is not dance music.

Ultimately, this group of Berlin-based musicians preferred to travel to alternative realities while sitting cross-legged rather than to stimulate the body to dance. Their effusive pieces extend for the full 20 minutes of one side of an album, so that the space journey is never interrupted, with no real climax, as unremitting as a trip to the furthest reaches of the inner self. This is also presumably why there are virtually no vocals on these recordings; the human element would only have irritated listeners.

This is one of several similarities between this and contemporary forms of electronic dance music like house and techno, which for their part almost do nothing but appeal to the body: the free combination of sounds and sound textures; long, rhythmically repetitive and thus hypnotic pieces without the standard verse-refrain structure; electronic instruments — all elements of today’s electronic club music in Berlin.

The abandonment and rejection of conventional music patterns and self-empowerment through new technologies are also motifs of both scenes. One used machines to descend into inner realms; the other lost itself in the external world, the world of dance clubs. “This new Berlin idealism rejected the cheap Carnaby Street capitalism on which much of the American and British scenes thrived,” Welsh musician and author Julian Cope would exclaim enthusiastically a few decades later.

Krautrock and cosmic music also attracted globally successful and aesthetically more conservative pop stars to Berlin from, of all places, the US and Great Britain. They hoped to find new inspiration here and booked the Hansa Studios for their recording sessions. “Recorded at Hansa by the Wall” can be read on several releases from this period.

This is where Lou Reed, for example, recorded his album Berlin in 1974, which celebrated the morbidity and gloomy niches of the half-ruined city. David Bowie recorded his Berlin trilogy (Low, Heroes, Lodger) here. Under the influence of producer Brian Eno, Low (1977) in particular makes use of the rhythmic repetition and electronic elements of krautrock. Eno had already worked together with Cluster and the krautrock band Harmonia.

Musicians Mufti and Blixa in Berlin in 1984. (Photo: Eva Maria Ocherbauer)

Musicians Mufti and Blixa in Berlin in 1984. (Photo: Eva Maria Ocherbauer)

Finally, Iggy Pop recorded The Idiot (1977) in Berlin, experimenting with industrial music references and drum machines. In the song Nightclubbing, which Grace Jones would later cover, he sings about time spent with Bowie in Berlin: ‘We walk like a ghost / We learn dances brand new dances / Like the nuclear bomb / When we’re nightclubbing’.

Ten Cities (Spector Books/Goethe-Institut), a book on clubbing in Nairobi, Cairo, Kyiv, Johannesburg, Naples, Berlin, Luanda, Lagos, Bristol and Lisbon between 1960 and March 2020, is edited by Johannes Hossfeld Etyang, Joyce Nyairo and Florian Sievers. This extract, on the emergence of krautrock in Berlin, is the fourth in a series of 10 weekly edited excerpts from the book.