Mongezi Gum, Celebrating Life, charcoal on paper, 2021.

Is it possible to read the work of Black artists away from the shackles of historical and political entanglement? And is it possible for Black artists and Black subjects to create fully in the spirit of absolute freedom?

I begin this text with these questions as a gesture to consider what the curators of the exhibition, Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt, seem to be nudging us towards. Named for a famous line from Kurt Vonnegut’s 1969 metafiction novel, Slaughterhouse-Five, the exhibition brings together artists who explore themes of rest, relaxation, leisure, intimacy and domesticity.

Curated by Anelisa Mangcu and Jana Terblanche, it reads like a survey of emerging and emergent contemporary voices engaging the Black figure in their practice. Mangcu and Terblanche, both of whom have spent years working in the contemporary commercial art landscape in various capacities, assembled the show around the concept of joy and freedom, articulating their interest in the conditions of Black creation and Black representation as follows:

“For much of recorded art history, Black people have been projected onto fanciful utopic or dystopic dreamscapes that underscore the extremities of their identities. Some of these depictions have been useful to honour the past and to imagine spaces that are ruled by a different, fairer set of relations. Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt, flips the proverbial script and engages artists who create moments of joy, freedom and upliftment.”

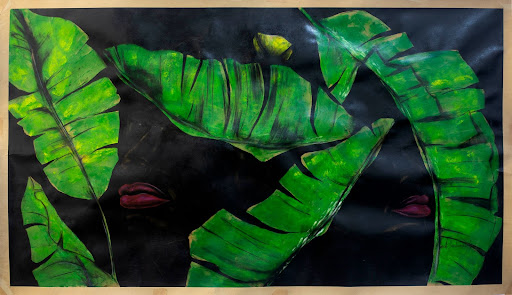

Navel Seakamela, Within My Space, charcoal, pastel and acrylic on paper, 2021.

Navel Seakamela, Within My Space, charcoal, pastel and acrylic on paper, 2021.

In the exhibition, narratives of Black life are illuminated through a combination of paintings, collages and mixed-media works. These conversations can occur only on the back of a long lineage and tradition of Black figurative art including, but not limited to, the works of Kerry James Marshall, Helen Sebidi, Faith Ringgold, Trevor Makhoba, Winston Saoli and many others. And this analysis too, of portraits of Black people and portraits by Black people, gleans and learns from the labour of disciplined and rigorous curators such as Dr Same Mdluli, through her 2019 exhibition A Black Aesthetic: A view of South African Artists (1970-1990).

A world in which “everything is beautiful and nothing hurts” is a world of joy, absolute liberation, pure artistic freedom, learning and growth — all these things are nice, but they are also not real … at least not yet. Just as the epitaph points to a deep dissonance and irony in Vonnegut’s tale, it raises scepticism and disorientation in our own world, because it is at once deeply beautiful and utterly credulous.

Perhaps this is what James Baldwin was thinking about when he wrote; “I can’t be a pessimist because I am alive. To be a pessimist means that you have agreed that human life is an academic matter. So, I am forced to be an optimist. I am forced to believe that we can survive, whatever we must survive.”

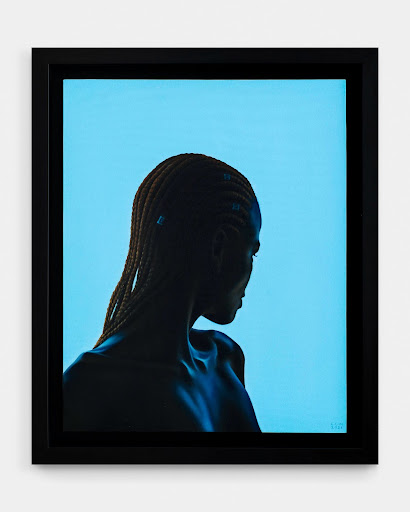

Craig Cameron-Mackintosh, Kitso, oil on Italian cotton, 2021.

Craig Cameron-Mackintosh, Kitso, oil on Italian cotton, 2021. But perhaps this is not what he meant, particularly if we believe that the road between fantasy and optimism is a long one. The tendency to view the more favourable aspects of a condition is still circumscribed by a rootedness in real conditions. And so we should wonder: What are the conditions within which Black portraiture is being produced and consumed?

And how far do those conditions lend themselves away from the reverie of utter joy and beauty where nothing hurts? Quite far, I would argue! The depiction of the Black figure, particularly in painting and photography, is currently taking place behind the backdrop of a market that is hungry for images of Black life.

Some of the problems we’re dealing with include the fact that Black portraiture has been (and continues to be) ruthlessly commodified in its display and consumption, Black portraiture has been (and continues to be) subject to objectification and that Black portraiture has been aggressively recontextualised to suit different agendas.

Any useful consideration of representation of Black life — even of the positive, optimistic and fanciful kind that we find in Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt, necessarily has to consider the undeniable proliferation and consumption of Black bodies.

Talut Kareem, If I don’t, who will, 2021.

Talut Kareem, If I don’t, who will, 2021.

In the opening scene of the documentary Black Art: In the Absence of Light, US journalist Tom Brokaw of The Today Show begins: “The black artist in America has had to put up with a great deal over the years. It has not simply been a matter of mastering the art while surviving as a person — this has been the experience of most white artists of course; for the black artist, it has also been a matter of being taken seriously as an artist and as an individual.”

Brokaw was speaking in the context of Black artists in the US on the eve of the monumental travelling exhibition, Two Centuries of Black American Art, curated by historian David Driskell. But of course, this condition of wanting one’s work and one’s life to be taken seriously, is a plea Black artists everywhere have had to consider, reflect on and fight for.

By assembling and deliberately considering art objects and artists in conversation with each other, curators mediate and author narratives and new forms of reading cultural production. What is exciting about Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt, is that it echoes the voices that have come before and offers a possible route to a very small fragment of what Black portraiture is or can be. What is disappointing, perhaps even damaging, is its limitations in adequately challenging or stretching what is often the problematic portrayal of Black imagery that is not aware of itself or aware of its consumption.

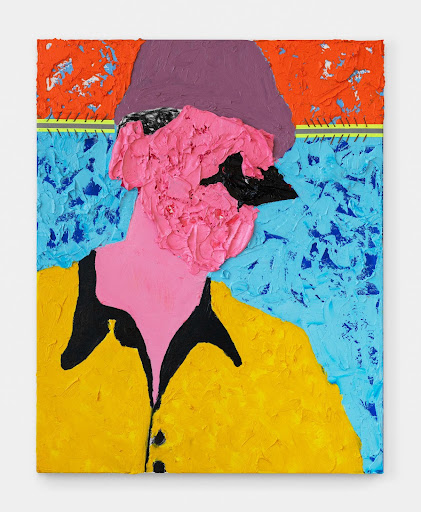

Perhaps this is countered somewhat by the inclusion of nuanced images, such as those found in Lwando Dlamini’s forms. In Selfie I (2021), Dlamini renders the self in an obscure, pinkish, eyeless and complex layer of paint. Instead of a direct representation of the self, we’re confronted with the “spirit” of what the artist seeks to communicate. This is once again visible in the work, Lulondwe Kubheka (2021), which is a portrayal of a young woman in a yellow shirt and coiled hair. Dlamini offers us something (not everything) in his retelling. He satisfies our gaze, but not completely, thereby subverting absolute and total consumption.

Lwando Dlamini, Selfie I, oil, reflective tape, thread and charcoal on tape, 2021.

Lwando Dlamini, Selfie I, oil, reflective tape, thread and charcoal on tape, 2021.

Exhibitions of this nature put work in front of the audience, but they also open up an avenue for critical engagement with the discourse of the time. Of course, one has to be aware of being too didactic and over-intellectualising the intent of the curator, particularly when the exhibition is mounted in the context of an art fair. As stated by curator Ralph Rugoff: “Our experience of an object and subsequent interpretation is shaped by the context that frames our encounter.”

Similarly, our interpretation of the artists and works included in the exhibition are affected by the locality in which they are staged, that is, the commercial space. That being said, a critical analysis of the decisions of the curator is useful, because it not only allows us to examine where power is located, but also ensures that we hold ourselves as Black creators and cultural producers to standards that positively contribute to our work, our lives and the work and lives of those who come after us.

Darby English instructs us that the figure is a sign of life and that aesthetics are, in fact, about the very question of human life, noting in an article (“Why the New Black Renaissance Might Actually Represent a Step Backwards”, Artnet, 26 February 2021): “The figure is a sign of life. And in a protracted series of deaths, signs of life are utterly crucial and need to be honored absolutely.” Through this reading, how we handle the figure is, in fact, a grave matter.

Everything was beautiful and nothing hurt is on view at the Keyes Art Mile in Rosebank, as part of FNB Art Joburg’s Open City. The exhibition will open on 28 October and shows until 14 November. Participating artists include Atanda Quadri Adebayo, Damilola Adeniyi, Adegboyega Adesina, Patrick Bongoy, Ikeorah Chisom Chi-Fada, Feni Chulumanco, Lwando Dlamini, Mongezi Gum, Talut Kareem, Zemba Luzamba, Craig Cameron-Mackintosh, Kimathi Mafafo, Muofhe Manavhela, Qhamanande Maswana, Sphephelo Mnguni, Buqaqawuli Thamani Nobakada, Mookho Ntho, Kelechi Nwaneri, Seth Pimentel, Navel Seakamela, Bara Sketchbook, Tafadzwa Tega, Katlego Tlabela and Lulama Wolf.