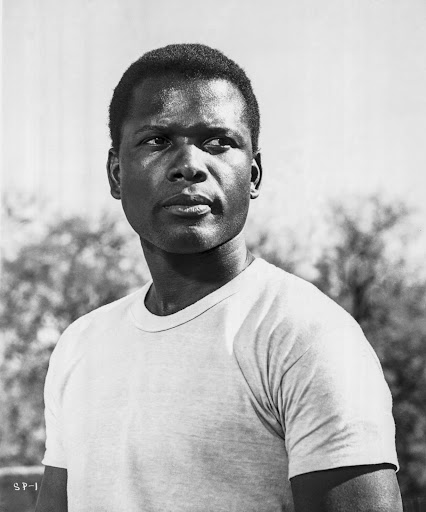

A scene from In the Heat of the Night (1967), in which Sidney Poitier (pictured here with Rod Steiger and Jester Hairston) is about to return the slap of Larry Gates, who plays plantation owner Mr Endicott. Image: United Artists/Sunset Boulevard/Corbis/Getty Images

Guess who’s gone to celestial dinner? The tall, beautiful man of African descent from Cat Island in the Bahamas via the United States of America, named Sidney.

Dear God: At 94, Sid is putting up and sleeping over in your not-so-spare room, and has not made any plans to swing back to this scarred, ghastly and sometimes, only sometimes, heart-tugging world.

As with Evelyn Preer, Anita Thompson, Hattie McDaniel (the first “Negro” to win an Oscar), Paul Robeson and others before him, his peers Dorothy Dandridge and friend Harry Belafonte, as well as director Oscar Micheaux (the first “Negro” director to bag an Oscar) and plenty other erased artists of African descent, the man came, saw and kicked down the gates in the only way he could.

Birth of cool

Sidney Poitier was born in February 1927 in the Southern city of Miami, Florida. According to Tashafi Nazir of The Logical Indian, “his family lived in the Bahamas, then a British colony, but he was born prematurely in Miami while his parents were visiting the city for the weekend”. He grew up in the Bahamas, but moved to Miami at 15 and New York City when he was 16 years old.

Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier in The Defiant Ones. Image: FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives/Getty Images

Tony Curtis and Sidney Poitier in The Defiant Ones. Image: FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives/Getty Images

A resourceful young man, Poitier joined the American Negro Theatre, landing himself a role as a high school student in the film Blackboard Jungle (1955). “In 1958, Poitier starred with Tony Curtis in the roles of chained-together escaped convicts in The Defiant Ones, which gained nine Academy Award nominations,” writes Nazir. “Both actors received a nomination for best actor, with Poitier’s being the first for a Black actor and a nomination for a British Academy of Film and Television Arts award (Bafta), which he won.”

He also received acclaim for Porgy and Bess (1959), A Raisin in the Sun (1961), and featured in Lilies of the Field, playing a handyman assisting a group of German-speaking white nuns build a chapel, for which he won an Oscar in 1963.

Black heat in the night

Almost all current reappraisals of Poitier’s ouevre omit his deliberate and dogged commitment to telling South African and – although mid-Century Hollywood directors sometimes imagined Africa as a country – continental stories.

The pictures themselves were not all ideologically progressive, neither did they all break racial stereotypes. Why would a future box office drawcard be offered such material? Your guess is as good as mine. But none of them were written, directed, produced and photographed by a Black technical crew.

Which is not to say production by Black talent is inherently exceptional. That’s just a reverse racist trap all progressives can live without. While it stings that Black mediocrity has never been given the same institutional support as Eurocentric and, Asian mediocrity in the history of 20th-century cinema, we should not be pining for it now, at least not at the expense of Poitier’s legacy.

Poitier featured in at least five films, three with specifically South African storylines: The Wilby Conspiracy (1975), Cry the Beloved Country (1951), Mandela and De Klerk ( 1997).

The Mark of Hawk and Something of Value (both released in 1957), were racial thrillers speaking to broader themes of white liberals stepping into their historical “knight in shining armour”, out to save tragic Negroes and African political outlaws, sometimes from themselves: Pfffff!

Representational politics devoid of the radical intent to overhaul the system so that it engages with new, spirit-altering, just and subversive ways of seeing, of being, is the end of us.

Poitier knew it then. He also understood you had to work with what you had. He knew what time it was. Although he would take flak from no-one, Poitier endured all that mainstream studios threw at him. Here was a man on a mission.

Roles for Black actors were scarce at the time, but Poitier followed up with A Patch of Blue (1965). He continued to break ground in three successful 1967 films that explored race relations.

While most of his films are consigned to museum film archives, two, Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner? and In the Heat of the Night stand out 55 years later.

In the Stanley Kramer-directed and -produced Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner?, he plays a widowed doctor who shocks his family by dating a young woman from a liberal white family, whose liberal values are rooted in the American race status quo.

Sidney Poitier with Katharine Hepburn, Katharine Houghton and Spencer Tracy in the Stanley Kramer-directed film Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner? Image: FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives/Getty Images

Sidney Poitier with Katharine Hepburn, Katharine Houghton and Spencer Tracy in the Stanley Kramer-directed film Guess Who’s Coming To Dinner? Image: FilmPublicityArchive/United Archives/Getty Images

The American pulse quickened and things got real hot in Norman Jewison’s In the Heat of the Night.

Filmed in a small Tennessee town while a demonstration by a bunch of conservative Southerners raged on outside the location, the film was shot, graded, edited and released during the tumultuous tableaux of civil rights movements.

In the Heat … tells the story of a Philadelphia detective who assists in a Mississippi murder case with a racist policeman and features some of the most poignant, even in-your-face, horse-kick moments in the actor’s filmography.

In one scene Poitier’s character slaps Larry Gates, who plays the plantation owner Mr Endicott. Any aspirant filmmaker worth his cinematic ambitions would, as I have in the last 30 years, have rewound the scene a million times.

The old, postcard-colour texture of the scene bursts into life precisely at the moment when Poitier’s detective Tibbs and Gillespie, played by Rod Steiger, visit Endicott to question him about a murder when Endicott slaps Tibbs. Unthinking, and armed with no theory or placards, Poitier’s Tibbs smacks him back: Hot and fast.

The dramatic scene heats up and climaxes in under two minutes, but the memory of it lingers on in film infamy. It quickly became known as “the slap heard round the world”.

In his 1994 book Blackface: Reflections on African-Americans and the Movies Nelson George, since then a successful film and television writer, director and producer, recalls encountering Sidney Poitier “with my mother at a Saturday afternoon matinee”. The chapter is titled Sir Sid.

“I was nine years old and I have never forgotten it and never will. In the Heat of the Night was the film that made me fall for Sidney. Even in the wilting Southern heat the second button on his suit always stayed closed. Anger flashed across his face when he slapped a racist Southern patriarch and shouted at Steiger’s sheriff, ‘I’m a police officer!’”

In 1967, the year of the “thunderous” clap, even though it was more like a silent Ali to Foreman jab, the whole world was still feeling hot and edgy with Sam & Dave’s insouciant and sticky Hold On, I’m Coming, released the previous spring, rippling through the radio.

The following year Martin Luther King Jr was assassinated in cold blood and Hugh Masekela’s Grazing In the Grass lit up a sonic inferno under the pop world’s ass. The world would never be the same.

Poitier’s life story was bittersweet, and, for me, laced with vinegar because of how the system has reshaped our communion with the recently departed, the ancestral realm, and turned elegy into a new media beat – the new “profile” feature of this age.

Sidney Poitier acted alongside Dorothy Dandridge in the film Porgy and Bess (1959). Image: Samuel Goldwyn Productions

Sidney Poitier acted alongside Dorothy Dandridge in the film Porgy and Bess (1959). Image: Samuel Goldwyn Productions

We strangle the dead with further, uncritical adoration. A pivotal figure passes on and the internet blares about him before the last air gasp escapes the body, and we all rush to consecrate the departed.

We make our names extolling the virtues of his or her work and symbolism without pausing for a moment to consider the inhumanity and erasure, often at a personal and family cost, they faced in the system within which they worked. We put them on pedestals mostly because we are embarrassed to confront that which ails us spiritually.

We also elevate them because we are invested, despite our protestations, in the system itself, in the American way, and the American popular culture. Black, Brown and Jewish folks damn-well built the industry, although at different access points.

When not allowed, we mugged, rewrote the rules to render it palatable to us. Performers such as Poitier, Belafonte, Robeson, Zakes Mokae, Miriam Makeba, and writers such as Langston Hughes, Zora Neale Hurston, James Baldwin, and to an extent Albert Murray, understood that the path towards Black cultural liberation would have to be stepped on and fought for through strategic initiatives.

They understood we’d have to be one with the revolutionary community in publicly rejecting the system, while offering each other succour and generative love, financial help too.

In those rare instances where artists were treated as individuals, still, in often-demeaning roles, they had to dig within the depths of their souls and creativity to portray rounder portraits that resonated with their communities.

From the late 1800s and to the 21st century, the story of Black and some Brown folks is the story of shouldering the yoke of your people. It is also the survivalist and creative mobility of code-switching, of keeping a few steps ahead of the system you could not immediately crush.

Poitier in Central Park, New York City, 1964, after winning an Oscar for his role in Lilies of the Field. Photo: Bettman

Poitier in Central Park, New York City, 1964, after winning an Oscar for his role in Lilies of the Field. Photo: Bettman

Rebirth of cool

The results, of course, are that Black creatives – both cargo and carriers of the responsibility to keep the country from imploding within its unsustainable moral and ethical flaws – had to work ten times more than everyone, and Black women even more, paying with their bodies and souls.

It is not the system’s magnanimity but its shrewd awareness that finds Chocolate Power in vogue; positioning itself to profit off Blackness’ ability not only to “shift” the culture but to remake it in its own images.

It is commonplace now for essayists and critics to extol the virtues of a particular cinematographer for “understanding” and lighting up different shades of Blackness on screen. It is all “cool”, all de rigueur.

The life and times of Poitier remind us “cool” was not even a factor; “cool” was not on the table, “cool” never depended on millions of clicks, generated likes and little red hearts.

“Cool” was something proffered to Humphrey Bogart, to Paul Newman. “Cool” was Steve McQueen, until Charlie Parker (immortalised in Clint Eastwood’s biopic, Bird), Miles Davis, Sammy Davis Jr, Billie Holiday and Miriam Makeba sweated over and died a million little deaths so we can live.

“Cool” screen and stage power was the province of all dreamers but children of African descent.

While there is pain and wretchedness just typing these words, we can now look a decade in its eye and say deadpan that when Barack Obama walked into the White House that historic winter of 2009, he was not the first “Negro” liberal to play the system with debatable success.

Film historians locate Poitier’s enduring power not in the films he made, but in the work of those he opened the gates for. Photo: Getty Images

Film historians locate Poitier’s enduring power not in the films he made, but in the work of those he opened the gates for. Photo: Getty Images

Poitier emitted a rooted unfuckwithability with a slip of a smile, all-white teeth, black kinks for hair, dark skin shimmering into Senegal blues against the sun, or so the film posters of the time tell us.

He was fresh and clean. Poitier was no cad with on/offscreen-raging-libido curated for African male stereotyping.

His piercing eyes, sometimes reduced into a slant not unlike Clint Eastwood’s in The Good, The Bad and The Ugly, sans the cigar, looked into your soul. Although he was often angry on screen, angry even when smiling and calling others “sir”, or “ma’am”, Poitier could never be Bigger Thomas. He knew he had to preserve that anger for far more important battles and joyous moments ahead.

He was not going to burn with blinding rage only to be lynched and roasted under sweltering heat, feet dangling under poplar trees. His quiet power parlayed into creating solid portraits on the screen, which he subsequently leveraged into regular work.

Film historians locate his enduring power not within the films he made, although they are testimonies of audiovisual excellence, but in the work of those he opened the gates for.

But the Black Saviour sentiment is a ruse.

So while Sidney Poitier’s symbolism was pivotal in the entire film-going experience featuring Black folks, (those inspired by him and those who created powerful, impatient art with radical and rattling nous) from 1969 onwards, his direct influence can be felt in the work of only a specific quality of actors.

Methodically speaking, and per temperament and silent intelligence on screen, there would not be a Denzel Washington, a Regina King, a Viola Davis, certainly no Chadwick Boseman and, who knows, no late-style Brad Pitt and no Andy Garcia, had Sidney Poitier never stepped up and, quietly, his words reverberating for all to hear, said in his formative 1950s:

“I, too, we too, matter.”

Bongani Madondo is an author of books on artists, Black magic, and subversive performers. He is the recipient of the Film Resources Unit’s once-off Djibril Mambety Recognition for Film Criticism (1997), and a filmmaker