André Leon Talley speaks at a screening of his documentary The Gospel According to André during the 21st SCAD Savannah Film Festival in Savannah, Georgia, 2018. (Photo: Clingy Ord/Getty Images)

In a viral 2016 Met Gala video clip, André Leon Talley makes some impromptu running commentary, capturing so poignantly Rihanna’s most iconic red-carpet moment. As she walked the carpet, looking like royalty in her canary-yellow Guo Pei cape, Talley immortalised this with a now-legendary take.

“I love a girl from humble beginnings who becomes a big star! It’s like the American Dream. That’s how you do it,” he said, injecting intellectual and cultural significance to what many wouldn’t perceive as anything beyond a frivolous celebrity moment.

Talley, who died last week at 73, stood out because “he was the rare Black editor at the top of a field that was mostly white and notoriously elite,” according to the New York Times. But he was so much more.

Behind the scenes, he worked tirelessly for the inclusion of black models on the runway and championed the careers of young black designers like Laquan Smith, among others.

Former US first lady Michelle Obama often wore black and African designers like Mimi Plange and Duro Olowu — a choice Talley, as her style adviser, no doubt had a hand in.

I first came across Talley in the 2000s, via the pages of Vogue magazine, where he was then editor-at-large. I take after my late mother: fashion was and remains one of my many interests, but I had no clue at the time that it would be something I would pursue as a career. This is partially because I had no interest in being a designer myself, and, in the pages of Vogue and other titles, I barely saw anyone who looked like me bar supermodels such as Naomi Campbell and the like — themselves a rarity in that world.

But when I landed on Life with André, the column Talley wrote for Vogue up until his departure in 2013, the seed was first planted in my mind that indeed, I, a queer black person could probably find a place in that world, too.

He wrote about fashion and celebrities with passion, imbuing the subject with intellectual gravitas. This is what got me excited about becoming a fashion writer, even though my career only began in what we now know to have been the dying days of fashion magazines, specifically, in South Africa. The space has since been filled by influencer marketing and almost nothing as far as any informed engagement with the work of designers and the culture behind fashion are concerned.

There is nothing inherently wrong with influencer culture, I might add. We move with the times, but I do crave a good read about this moment when local designers like Thebe Magugu, Rich Mnisi, Sindiso Khumalo and Lukhanyo Mdingi are taking our stories to the world in a way no generation of designers did before them. Are there any others following in their footsteps? If not, why?

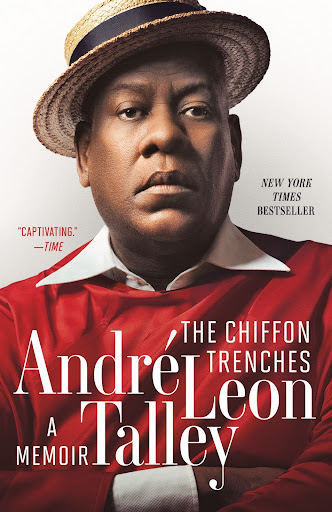

André Leon Talley’s memoir was published in 2020.

André Leon Talley’s memoir was published in 2020.Fashion may seem fantastical and whimsical. However, on closer inspection, you come to realise that it is coded with history and glimpses of the future. This is something that has always struck me as important and worth documenting — not just in pictures, but also in words — to give historical and cultural context and significance to each of those moments.

Why does it matter? Why should we take it seriously? These are some of the questions the fashion journalist must answer. This industry makes a product we use not only to invent, but also to perform our identities — chosen or otherwise. So what does it say about who we are?

These are the factors that make interrogating fashion necessary: it gives us a window into how the world around us is changing.

It’s Chanel making trousers a key piece in women’s closets as the world shifted towards demands for gender equality. It’s Stoned Cherrie and Loxion Kulca being the proverbial costume for a post-apartheid cultural revolution as we sought to decolonise and forge a modern black South African identity, unshackled by the paralysing grip of oppression.

The ability to capture these moments is what intrigued me most about fashion, and indeed, the way Talley injected this journalistic integrity into his musings about fashion and style was the spark.

It’s because of Talley and others like him — Cathy Horyn, Suzy Menkes, Robin Givhan — that I decided to go into fashion journalism, pursuing a career that barely existed in South Africa. It quickly became apparent to me that few editors were interested in this. However, I found a few who were, among them Jacquie Myburgh and Jackie May from whom I inherited the Timeslive blog, The Frock Report, which I co-authored with Sarah Badat.

The Frock Report and later the Mail & Guardian, under then Friday editor Zodwa Kumalo, allowed me front-row seats at South Africa’s many fashion weeks in the early part of the past decade. It’s an industry that struck me as reflective of much about South Africa: The lack of funding and opportunities; the paralysis induced by competing institutional interests; the lack of popular support that I saw as a reflection of how we often look down on anything homegrown; how connections, or the lack thereof, can either make or break careers.

For me, it was never enough to simply look at the garments and stew in the glamour of the parties and events I was often invited to. It was necessary to understand what was going on behind the scenes. What were the designers thinking about? What challenges did they face? How does that fit into the ever-changing norms of society?

This way of doing things is what shaped my approach to viewing fashion as a medium through which we can gain a better understanding of the world around us.

Had Talley not been the trigger for my interest in pursuing fashion writing, my approach could have easily been devoid of this critical engagement with the industry. I definitely would never have known that I — a black voice — could find a place in fashion.