A view of the exhibition You to Me, Me to You at A4 Arts Foundation in Cape Town.

Cultural clichés are like a blunt axe. Take Mexico. If the marketers of a local tequila and spicy chicken brand are to be believed, Mexico is a place of fearsome Mesoamerican Olmecs and hardy revolutionaries in sombreros à la Pancho Villa of a century ago.

Of course, these essentialist corporate fantasies about national cultures exist everywhere. Can artists — a frequent-flyer class who rival politicians and business leaders as emissaries from elsewhere — make a difference? Perhaps, but it is slow and incremental work destabilising a cliché.

Over the past year, without much razzle-dazzle, art and artists from Mexico and South Africa have been engaged in conversations with audiences in the two countries.

It started last year with a long-delayed exhibition of Mexican painter Frida Kahlo in Johannesburg — the first time a work by this Hollywood-grade artist had been exhibited on the African continent.

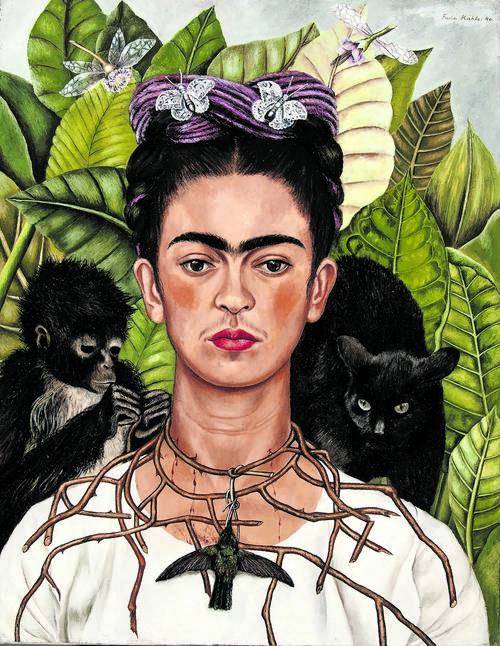

Hosted by the Joburg Contemporary Art Foundation, the exhibition Kahlo, Sher-Gil, Stern: Modernist Identities in the Global South featured a 1940 self-portrait of Kahlo wearing a thorn necklace and hummingbird pendant. It bristled with psychic energy. Of course, bookings for this reticent private museum in Forest Town spiked.

In March, Kahlo’s painting — originally a gift to her lover, photographer Nickolas Muray — returned to its owner, the Harry Ransom Center at The University of Texas at Austin in the US.

Three months later, acclaimed ceramicist Clive Sithole travelled to the mountain town of Tapalpa in Mexico to present a workshop at the National School of Ceramics. Sithole, a master potter who was briefly trained by Nesta Nala, demonstrated his superb technique.

This included showing how to shape, decorate, fire and burnish a traditional Zulu beer pot or ukhamba. The workshop was also a learning opportunity for Sithole, who was surprised by the form and daily functionality of Mexican ceramics.

“It caught my attention that in Mexico pottery is used in utilitarian pieces,” Sithole told a local journalist.

“We stopped doing that a long time ago. Ceramics are preferably used for ritual and/or decorative objects.

“In KwaZulu-Natal culture, ceramic pieces are used to serve beer when receiving visitors and also for certain rituals.”

Earlier this month, painter Georgina Gratrix — who was born in Mexico City but grew up in Durban — opened a solo exhibition of new paintings at contemporary art gallery Proyectos Monclova in her birth city.

Titled Colima 302, the exhibition includes examples of Gratrix’s opulent flower still lifes, candid portraiture and tchotchke-like dog sculptures. There is also a fabulous blobby self-portrait in purple — it makes Kahlo’s charged work feel po-faced.

Gratrix has been in Mexico on an extended sojourn while her Cape Town home is renovated and the dust settles after leaving her long-time gallery for Stevenson.

The jubilant paintings on her exhibition were all made in Mexico City. Some were inspired by a visit to Mercado de Jamaica, a flower market known for its animal figures made entirely out of flowers. Her exhibition includes two joyous paintings of lapdogs as flower bouquets.

Gratrix paints like an over-stimulated confectioner, more so when she depicts power people — as in her 2019 portrait of dealer Liza Essers, coyly catalogued as Woman with Sunglasses in a recent auction catalogue by Strauss & Co.

Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird. (Copyright Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera)

Frida Kahlo’s Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird. (Copyright Banco de Mexico Diego Rivera)

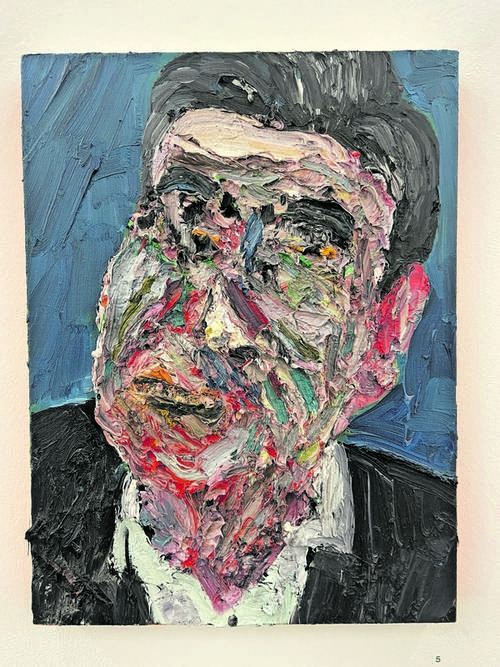

In 2019 Gratrix painted The Insomniac. It is hard to fully account for the facial features of the male figure. To summarise, his face is an agitation of paint.

For a number of years, this portrait has served as the WhatsApp profile picture of the Mexican curator Francisco Berzunza. The painting is also part of Berzunza’s ambitious group exhibition at A4 Arts Foundation in Cape Town.

Titled You to Me, Me to You, the show includes major international figures such as Bas Jan Ader, Sophie Calle, Moshekwa Langa, Tina Modotti and Dayanita Singh, alongside newcomers such as Thato Makatu.

Similar to Berzunza, Makatu had a peripatetic upbringing in a diplomatic family and is completing her final year at the Michaelis School of Fine Art in Cape Town.

Notwithstanding the strong representation of Mexican and South African artists, Berzunza’s exhibition is less motivated by the possibilities of cultural diplomacy than it is about exploring an idea.

Can love be a viable theme for an exhibition? Berzunza thinks it can.

“Love is a human experience; we are all invested and interested in human emotion,” he explains in a guide accompanying his exhibition.

During a public walkabout he elaborated on his motivations.

Last year, after a tour of the ministry of public education in Mexico, Berzunza sat at the feet of Diego Riviera’s 1922 mural The Assembly and declared his love to the straight man accompanying him.

“I get that we are not friends nor lovers, so what are we?” responded Fernando.

“Well, I am Francisco to you, and you are Fernando to me.”

And thus an exhibition title was coined.

“Love can be the desire and the frustration of becoming one with another,” explained Berzunza.

“This exhibition explores — through new commissions and historical works — the impossibility of this affirmation, as love may well be the act of sharing our loneliness with each other.

“That, more or less, is what guides this exhibition, the story between another person and myself and this exploration of love as an act of sharing loneliness.”

Group exhibitions — like the mixtapes of old and the Spotify playlists of today — are necessarily subjective for viewers. This works for me, that not so much.

The abundant photography was, for me, an unexpected treat, more so given its death at market and consequent disappearance from the local gallery scene. You to Me, Me to You has strong photographic contributions by Manuel Álvarez Bravo, Thembinkosi Hlatshwayo, Pieter Hugo, Graciela Iturbide and Jo Racliffe.

The tragic Dutch conceptualist Ader, who died during a solo Atlantic crossing, is represented by an expanded version of his mercurial photo essay In Search of the Miraculous (One Night in Los Angeles). The work was made in 1973 as a precursor to his ocean crossing. It is a strange work, an episodic record of an artist’s walking search for something in the urban interstices of nighttime Los Angeles.

“Certain things,” writes the Mexican author Valeria Luiselli, “elude direct observation. Sometimes it’s necessary to create an analogy, a slanting light that illuminates the fugitive object, in order to momentarily fix that thing that escapes us.”

This observation by Luiselli — it appears in her debut book of essays Sidewalks published in English in 2014 — doesn’t neatly explain Ader’s journey or Berzunza’s love quest but somehow it illuminates them.

Georgina Gratrix’s painting The Insomniac. (Frida Kahlo Museums Trust)

Georgina Gratrix’s painting The Insomniac. (Frida Kahlo Museums Trust)

The daughter of a diplomat, Luiselli spent a substantial part of her youth in South Korea and South Africa. English became her language of discovery, of reading and writing.

She met Nelson Mandela, twice. When she told the statesman with “deep, deep grey eyes” she wanted to be a prose writer, he responded, “Well, then you need to read a lot.” Luiselli’s dazzling literary essays bear out her catholic reading habits.

Like Luiselli, Berzunza also has strong biographical connections with South Africa. He first visited the country — fittingly — after a breakup and quickly fell in with local artists.

He completed a master’s degree at the University of Cape Town, focussing on coins from the Cape Colony minted with American silver. He later worked as a cultural attaché for the Mexican embassy.

In 2018, then still in his twenties and brattishly ambitious, Berzunza curated a large-scale exhibition of South African art in Oaxaca, in southern Mexico. Titled Hacer Noche, it included fascinating moments, especially a selection of sculptures by Dumile Feni, Nelson Mukhuba and Johannes Segogela that chimed — formally and thematically — with pre-Hispanic Mesoamerican and Catholic-influenced Mexican art. A biennale-like showcase of African art followed in 2021.

Mexico, a country that decoupled from the Spanish Empire in 1821, offers many insights for South Africans negotiating three decades of independence. The past is not easily undone. Equilibrium is a struggle.

In 2005, during a visit to Joburg to deliver the Nadine Gordimer Lecture at Wits University, essayist Carlos Fuentes described the early democratic Mexico as “a Nescafé republic, an instant democracy”.

Can the experience of art contribute to building mature political citizenship? Berzunza, who considers himself a historian rather than a curator, thinks “yes”.

“When one lives among endemic inequality and injustice, the real way to help, if one believes there is the possibility of effecting change, is through politics — exercises that have a political repercussion in the public arena,” Berzunza told A4’s Josh Ginsburg in an interview.

“An exhibition can be a laboratory of politics.”

A politics inflamed by love and the desire for cross-continental connection.