Move over, Jean-Michel: Zimbabwean Gresham Nyaude

The winner of the 2024 FNB Art Prize, Gresham Nyaude, grew up in a parallel artistic universe. His dad was an illustrator at Parade magazine in Zimbabwe and, in their Mbare township home outside Harare, drawing outside the lines was literally encouraged.

“I’ve got two siblings, two sisters,” the 36-year-old painter tells me in a Zoom interview from Harare. “So, everyone at home was just drawing, scribbling on the walls and stuff. And we were never forbidden to do that.”

But at school it was a different story, he says with a chuckle.

“I often had these problems at school … there, we were not allowed to do those things.

“All the time my homework book was full of drawings instead of the homework.”

There was another thing that left him stupefied.

“Honestly, I grew up thinking that everyone could draw or paint. I thought it was sort of, like, normal for everyone to do it. I didn’t know it was a challenge.”

One thing that surprised nobody was when Nyaude decided to become an artist after he finished school in 2004.

His classmate, Wycliffe Mundopa (a previous winner of the prestigious FNB prize), told him about an art workshop at the National Gallery of Zimbabwe in Harare.

After completing this two-year beginners’ art course, Nyaude quickly found out one needed resilience to become an artist in Zimbabwe.

“There were no real institutions that would support you. There were galleries — but not enough galleries.”

And there were further obstacles to those existing galleries. When the Queen Mother visited Zimbabwe (then still Southern Rhodesia) in 1957, she donated some European art to the national art gallery.

“So, for them to take off that work on the wall and put up yours, you need to really work hard,” Nyaude says.

There were also limited spaces to work from. He, Mundopa and another now well-known artist, Moffat Takadiwa, convinced the city council to let them use an abandoned preschool in Mbare.

“They said, ‘Okay, as long as you clean our space, you can use it for whatever activities you want to do, as long as it’s not illegal …’”

Filling the space with work was not an easy task with zero budget in a struggling country — materials were hard to come by.

The intrepid artists would go to the dumping site of Zimbabwe’s main newspaper The Herald to look for old ink and unused paper.

“You can salvage some materials, and you can come back home and paint,” Nyaude says.

With their subject matter, they started to get international recognition but because of the poor materials they used, the technical quality was low. Through the Delta Gallery in Harare, Nyaude got access to proper paint, brushes, canvases and other materials. I ask him what it was like seeing his first painting after that.

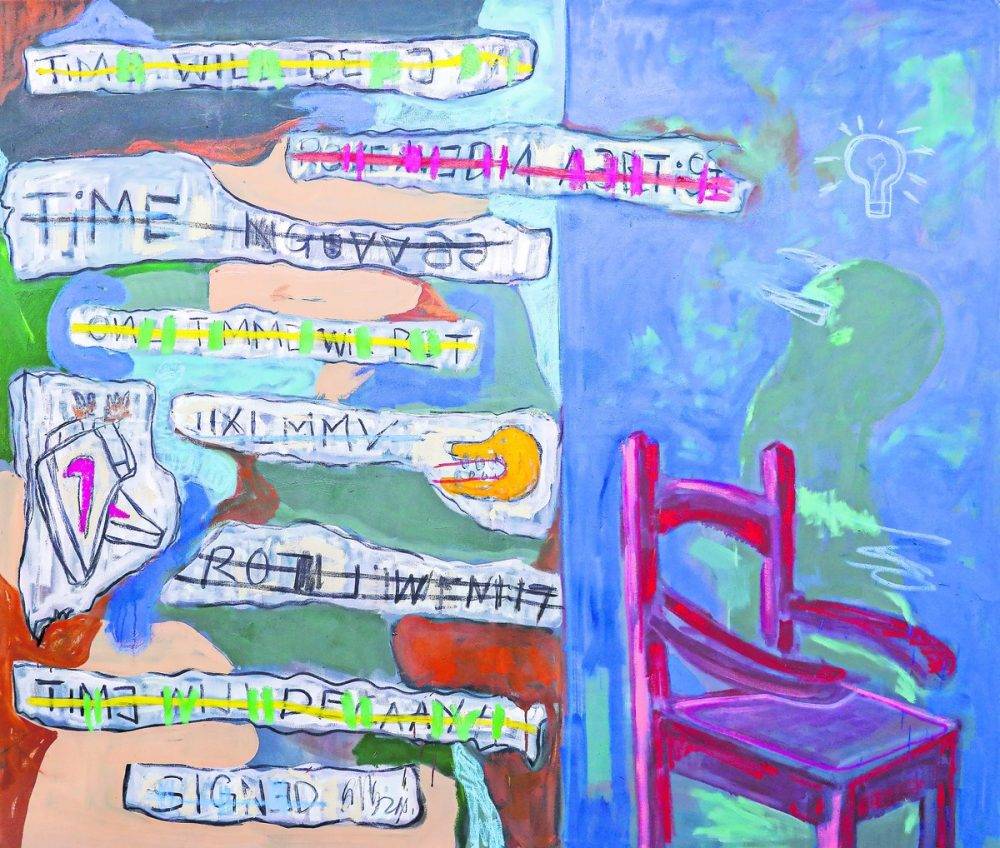

Zimbabwean Gresham Nyaude’s work MCMLXXXIV

Zimbabwean Gresham Nyaude’s work MCMLXXXIV

“It was super-exciting but the painting was a disaster,” he smiles.

But it taught him that working with oil and acrylic paints was a “totally different ballgame”.

“I spent three years just learning how to mix colour, to be satisfied with working with paint.”

In 2008, he did a two-person show with Anne Zanele Mutema.

“People were, like, ‘Oh wow, you are like [American artist Jean-Michel] Basquiat …”

“Is it a fair comparison?” I ask him.

“Oh no, the one is a legend,” he responds with genuine self-deprecation. “Growing up like in Mbare, there’s always going to be this [similar] street energy which is influenced by music, fashion and everything.”

Nyaude gives further perspective.

“The response was, like, ‘Wow, his works reminds me of Basquiat,’ not, ‘Oh, this looks like Basquiat.’”

Nyaude is clearly not the African Basquiat — but very much the Nyaude of Mbare. Over his 16-year-long career, his originality has catapulted him to international acclaim and collector recognition.

In 2018, he presented a major body of work in the US as part of Songs for Sabotage at the New Museum Triennial in New York.

His work is in the Smithsonian National Museum of African Art in Washington and in numerous notable private collections.

Nyaude is not shy to use “inside” satire.

“Right now, like in a lot of countries, there are certain things that you are not allowed to say directly in Zimbabwe. But the people have created a language, a Shona slang, to criticise the government.”

As a people’s painter Nyaude is tuned in.

“I try to translate it into a visual language, I paint slang.

“I ask: how does it look as a painting? How do I express it? Okay, which colour?”

Nyaude constantly takes notes in his diary when he is out and about.

“And when I’m in the studio, I read those notes and I translate them into a painting.”

He is prolific, currently working on six paintings at the same time.

“They feed each other — and I’m solving a problem, I put it in colour.”

Nyaude is careful not to be too “bougie” with his work.

“When I do my work, I want, first of all, people from my township … they don’t have that much access to galleries, but when they come to the gallery, I want them to see themselves in the works.”

These often feature sneakers.

He explains: “So, sneakers, it’s an important thing in Zimbabwe. You must wear sneakers, good sneakers — brands.

“And in my works, after you have seen the sneakers, you like them, you start to like the painting.

“You try to understand what it is about, and we end up having a conversation, we end up talking about important things, and maybe helping each other progressing.”

Also, there is a lot of graffiti now in Mbare, says Nyaude, which is why it also features in some paintings.

“So, if anyone accesses the gallery, they go and tell each other, ‘You know, in the gallery, there’s things that we can relate to.’

“The gallery isn’t just old white people looking at art and the young people are not really involved.”

While Nyaude is delighted by his prize — his work will be displayed at the FNB Art Fair next month, followed by a solo exhibition later at the Johannesburg Art Gallery — he does feel the pressure.

“I really need to pull up my socks, like, I mean, I respect all the other artists who won this award before me,” he says with a grin, “and I wouldn’t want to be the artist about who they say, ‘Okay, this award was fine until Gresham came in …’”

The FNB Art Fair takes place between 6 and 8 September at the Sandton Convention Centre.