(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

In the 1960s, when I was a child growing up in Joburg, the apartheid government used radio for racism.

There was no television, let alone internet, back in those days. Only state-owned and controlled radio. Still, that was a strong tool to build up white identity and beat down black identity.

This instrumentalisation of radio — using it to achieve a political goal — meant highlighting apparent common white interests between white Afrikaans and English speakers, despite historical animosity between these groups.

Radio stations existed in these two languages, but they worked to construct a shared narrative across them — building whiteness as a stronger identity than those of “Afrikaner” or “Engelsman”.

Meantime, radio in African languages was designed to reinforce tribal distinctions, with each service focused on rural life and respective “homeland leaders” (who were stooges and lackeys). Certainly, radio was not allowed to reflect the commonality of oppressed black experiences.

But growing up in a white household, I’d sometimes hear the kwela pennywhistle of Spokes Mashiyane being broadcast on what was then Radio Zulu, and I’d take heart that this was the cultural promise of a united South Africa.

Mainly though, I would overhear the SABC English service when my parents tuned into it from time to time. Mostly, the music menu was of the deadly-dull “chamber” variety. In other words, downright dreary.

But the news was more dramatic — about what white men in government were doing — and about how the hostile outside world was threatening South Africa.

In the evenings, the news was followed by pseudo-spiritual platitudes presented under the slot called “Think on These Things”. Probably the idea was to add religious and intellectual credibility to the propaganda.

There was also, back then, an accompanying editorial comment after the news. It was designed to guide listeners about how to interpret what they had just heard, just in case they didn’t get the spin themselves. This dose of identity-building then sequenced into sentimental melodies, seductively titled “Music in the Blue of Evening”.

In short, the use of radio in the sixties was designed to lull white listeners into feeling reassured and secure. They need have no worries about the state of the country because, led by the trusted Nationalist Party government, unity under a dominant white racial identity would fend off domestic or international dangers.

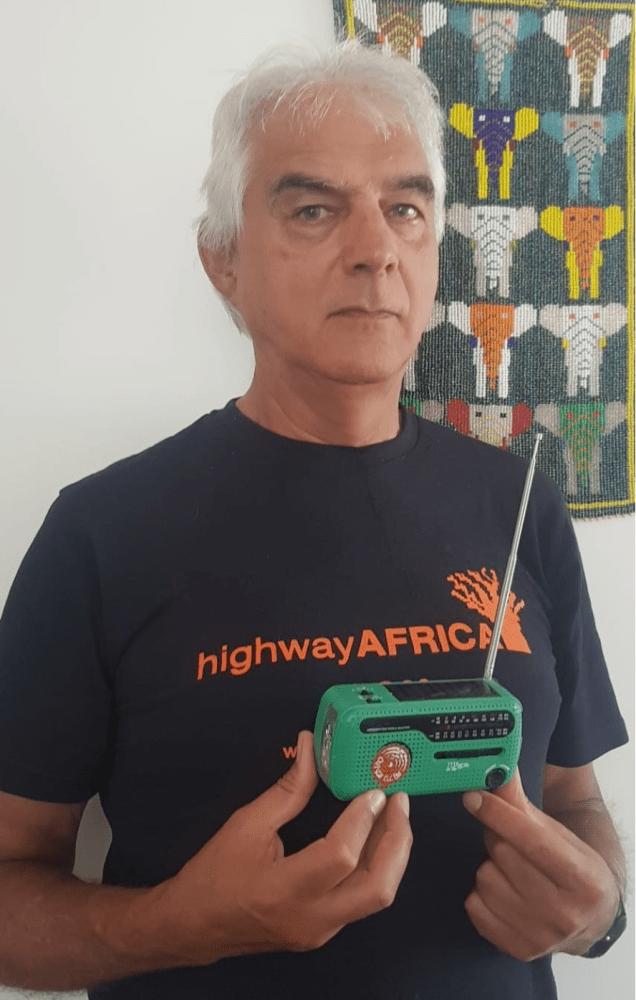

FM Love: Journalist Guy Berger shares his recollections of radio as a political tool

FM Love: Journalist Guy Berger shares his recollections of radio as a political tool

This bubble persisted into the 1970s. Epitomising it in that decade was Forces Favourites on Springbok Radio.

In this programme, listeners could request particular songs for conscripts in the South African army, along with an individual family message that would be read in English or Afrikaans by the honey-tongued announcer Esmé Euvrard.

Described as being a service to the “boys on the border”, the project of this programme was to boost morale among the white troops — never once questioning that many were not actually on the “border”.

Not in the sense of the South African national border, but instead were being deployed on (and over) the border between then occupied South West Africa (today Namibia) and Angola.

The basic apartheid project was not viable simply within narrow national borders — it required white soldiers being sent out, in various forms, across the wider southern Africa, and propaganda radio to reinforce this.

There was another side of this geographical “cordon sanitaire” — protective barrier — around white unity. Many South Africans had been forced into exile and continued to resist white supremacy from outside the country. They were the ANC, Pan Africanist Congress, and later, Black Consciousness adherents.

It was the ANC that proved most successful in reaching out across the airwaves to bring a different message to compatriots back home. This was through Radio Freedom, a shortwave radio transmission from several places outside South Africa, and targeted mainly at black South Africans.

But in line with the ANC’s historical non-racialism, these broadcasts were not aimed at uniting black against white, but at building the widest possible rainbow coalition against the apartheid regime.

Resistance to racism picked up inside South Africa in the mid-1970s, and this brought some whites to reject their identity and break with complicity from apartheid.

In this context, as a conscientised university student in that period, I experienced Radio Freedom to be a cascade of fresh water in contrast to the deserts of the SABC. With a call signal of bursts of defiant machine-gun fire and militant freedom songs, Radio Freedom was a powerful mobiliser.

While SABC radio sought to keep white audiences asleep, the voice of the banned ANC worked to inspire young people with fighting spirit. It was when you could pick up the ANC station, given that there was a cat-and-mouse game with the apartheid authorities always trying to jam the signal.

Just when you would try and tune your dial into the familiar frequency for Radio Freedom, you’d find the sound of a bokmakierie bird endlessly looping in its place.

It meant you had to keep exploring other spots on the airwaves in order to find the station, knowing all the while that listening was prohibited and that you could be bugged or reported by police spies.

The courts would construe your listening as furthering the aims of a banned organisation and so deserving of a stiff jail sentence. Obviously, producing real-time news from inside South Africa was not an easy enterprise for the ANC’s clandestine radio, and its role was less journalistic than mobilisatory.

But two new radio outlets emerged in the Seventies/Eighties with actual news correspondents spread around the country. These were able to broadcast by being formally based in areas declared to be independent states by the government, Transkei and Bophuthatswana.

The services, Capital Radio and Radio 702, were in English only. But still, they reached across language divides with their independent and often live journalism — despite serious harassment of their correspondents.

Today, listening to radio during commuting is still a major component of many people’s lives, as is hearing it in shops and homes.

It is a pity, though, that mobile phone handsets were not historically required by regulation to all have built-in FM receivers, because much more listening would then have been enabled. Nevertheless, radio remains an essential resource, representing fountains for South Africa’s diversity — and we need even more options today to reflect our many languages, interests and localities.

Against all this background, it was a personal pleasure for me when I worked at Unesco to have played a part in the international proclamation of World Radio Day. Now, each year on February 13, radio stations worldwide celebrate this unique service to humanity.

We owe a lot to radio, and thanks to press freedom and professional journalism, future generations of South Africans will continue to benefit from the uniqueness of this platform.

• For a copy of My Radio Memory: Listening to the Listener, email [email protected]. It costs R390 inclusive of delivery through Internet Express.

Guy Berger is an independent media expert. He led assignments for Unesco in the area between 2011 and 2022, and was previously head of the Rhodes University School of Journalism and Media Studies. Guy was a political prisoner under apartheid from 1980 to 1983.