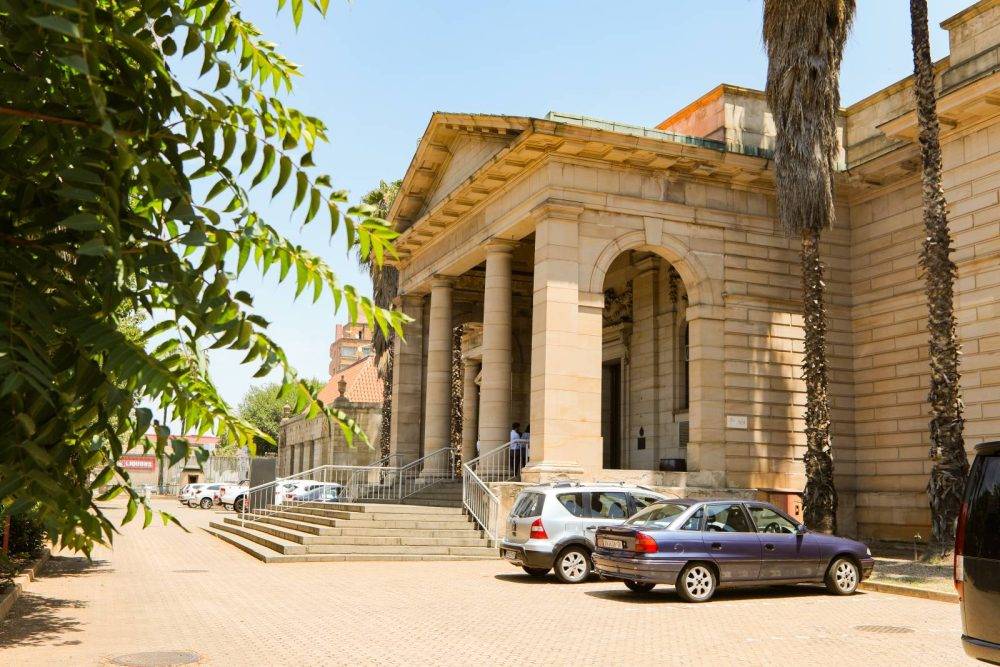

Once a cultural beacon, the gallery is a stark symbol of systemic neglect, reflecting the city's broader challenges and missed opportunities in harnessing its creative potential.(Photos by Gallo Images/ Fani Mahuntsi)

For over a decade, the Johannesburg Art Gallery (JAG) has faced persistent challenges with little progress.

Every year, public concern resurfaces over the potential loss of one of South Africa’s most significant art collections and the ongoing deterioration of the gallery’s infrastructure.

Situated next to a bustling taxi rank and Joubert Park in one of Johannesburg’s most densely populated areas, JAG’s location is seen to amplify these difficulties.

Attention on JAG typically flares up in response to social media outcries, news coverage and calls for action. Yet, this attention fades quickly, leaving the gallery’s plight unchanged.

Despite the escalating situation, neither JAG’s management nor the city’s department of arts and culture has provided transparency or viable solutions.

This year, tension peaked when the director of arts and culture for the City of Johannesburg barred an oversight committee from accessing certain parts of the gallery.

Why does this neglect persist? Why is meaningful intervention absent? The issues at JAG are not isolated but symptomatic of systemic failures in Johannesburg, reflecting challenges that extend far beyond the gallery’s walls.

The untapped potential of Johannesburg’s cultural and creative industries

Globally, the cultural and creative industries (CCIs) are recognised as powerful drivers of social, economic and cultural development.

In recent years, international organisations have emphasised their transformative potential, with the UN designating 2020 as the “International Year of the Creative Economy” and the African Union naming 2021 “The Year of Arts, Culture and Heritage: Levers for Building the Africa We Want”.

In South Africa, the cultural and creative industries (CCIs) contribute 3% to the national GDP, matching the agricultural sector’s economic impact.

Gauteng is the leading contributor, accounting for 46.3% of the sector’s GDP and creating the highest number of jobs in the field. As Gauteng’s economic and cultural hub, Johannesburg hosts the majority of the province’s creative businesses.

However, despite its vibrant creative economy, Johannesburg is not recognised as a Unesco Creative City — a designation requiring municipal leadership to spearhead the application process.

South Africa has three Unesco-recognised Creative Cities: Cape Town (design), Overstrand (gastronomy), and Durban (literature).

Without bold reform, JAG will remain a stark symbol of missed opportunities and systemic neglect.

Without bold reform, JAG will remain a stark symbol of missed opportunities and systemic neglect.

While Gauteng’s 2030 Growth and Development Strategy identifies CCIs as a high-growth sector, alongside agro-processing and the digital economy (which also falls within the CCIs), this vision is absent at the municipal level.

The city’s own Growth and Development Strategy 2040 fails to even mention CCIs, as does its profile, highlighting the disconnect between provincial ambitions and local implementation.

Perspectives from Johannesburg’s creatives

A recent survey of cultural and creative practitioners in Johannesburg revealed striking insights. Seventy-four percent of respondents worked in the inner city and Johannesburg South.

Using an eight-factor metric — education, leadership, infrastructure, culture, government policy, technological innovation, creative clusters and diversity — practitioners rated Johannesburg’s creative economy as unsuccessful in six areas. Only diversity and culture showed mixed results.

JAG epitomises these broader challenges. Its deteriorating state mirrors the struggles experienced by many in Johannesburg’s creative sector.

Creative hubs thrive while JAG declines

Amid the city’s lack of support for CCIs, a contrasting trend emerges — the rise of creative hubs. These provide essential resources such as studio spaces, market access, skills training and exhibition opportunities. A mapping study identified 19 hubs in Johannesburg, 17 of which are in the inner city

In stark contrast, JAG struggles to attract more than 5 000 annual visitors (a pitiful average of 417 visitors a month), often blaming its location.

Yet, within a 5km radius, thriving creative hubs host open studios — the Contra Fair alone had over 2 000 attendees in 2023 over just 2 days — engage communities and drive sector growth, proving that location is not the issue but rather leadership, innovation and relevance.

JAG’s governance “black hole”

As worded in a recent article by Giulietta Talevi and Ferial Haffajee, JAG has the strangest “black hole” when it comes to governance. No one seems to be responsible.

Gallery staff continually blame the city and say they have all signed a confidentiality clause in their employment contract and, therefore, cannot speak to the public or the media.

The Art Gallery Committee has stated that it is simply an advisory body and has no jurisdiction to make decisions or speak on behalf of the gallery or the city.

The city, under director of arts, culture and heritage Vuyisile Mshudulu, refused to respond to questions for this article, or to engage with media and the public. The Friends of JAG say they have no authority or power.

It is truly a black hole, even though the deed of donation, signed in 1913, is very clear about where the responsibilities lie.

According to the chair of the Art Gallery Committee, the council intends to fulfil the mandate outlined in the deed in the most effective and practical way, given the current situation.

It is unclear what that means with no timelines, no inventory of the collection and no clarity on loaning agreements or accountability. According to the deed, the mayor of Johannesburg should be on the committee, which is no longer the case.

The collection, donated in 1913 by Florence Phillips, Otto Beit and Max Michaelis, was gifted under a deed of donation, which outlined specific management requirements. It designates an committee, chaired by the mayor, as the oversight body for decisions regarding the collection, including loans and sales.

However, there are indications that the committee no longer fulfils this role. The Friends of JAG, established in 1976 at the request of the mayor’s office, boasts a 48-year legacy of collaboration with the curatorial team. This partnership, however, appears to have waned in effectiveness, further compounding the gallery’s operational challenges.

Proper storage and preservation of its collections remain unmet needs, while its leadership lacks the vision to align the gallery with the CCI objectives of the provincial government.

Proper storage and preservation of its collections remain unmet needs, while its leadership lacks the vision to align the gallery with the CCI objectives of the provincial government.

A vision for JAG’s transformation

JAG faces significant challenges that stem not merely from insufficient funding but from structural and strategic deficiencies, including outdated operational models, ineffective leadership and a failure to adapt to evolving demands.

As a traditional “white cube” gallery, JAG has struggled to align itself with the broader needs of Johannesburg’s creative economy.

The term “white cube” was coined by Irish art critic Brian O’Doherty to describe the way in which art is shown in what initially appears a neutral space, but is layered with financial, intellectual and social snobbery and exclusion.

Despite its impressive collection, the gallery remains disconnected from its local context. This misalignment undermines its potential relevance and impact.

To regain relevance, JAG must evolve into a dynamic creative hub that fosters innovation and cultural exchange. By introducing artist-support programmes, incorporating a restaurant that celebrates local cuisine and offering engaging spaces for community interaction, JAG could become the centrepiece of Johannesburg’s creative industries.

Such a transformation would probably make securing funding for restoration and development more feasible.

JAG’s siloed approach hinders meaningful collaborations with public, private and national institutions. A systems thinking approach not only would allow for more substantial progress and partnerships, but also for a more relevant and direct connection with the distributed nature of the CCIs.

Proper storage and preservation of its collections remain unmet needs, while its leadership lacks the vision to align the gallery with the CCI objectives of the provincial government. This broader misalignment reflects not only on JAG but also on Johannesburg’s cultural strategy as a whole.

A call for leadership and strategic reform

JAG’s challenges underscore deeper systemic issues in Johannesburg: fragmented decision-making, limited cross-departmental collaboration and a lack of appreciation for the economic and social impact of the CCIs. The absence of a cohesive municipal vision for the sector further compounds these problems.

Incremental efforts, such as small-scale workshops, fall far short of addressing the magnitude of the issues. To unlock JAG’s potential and elevate Johannesburg’s CCIs, the city must:

- Recognise the value of CCIs as powerful drivers of economic and cultural growth, which requires a deeper understanding of the industry’s complexity and distributed network — growth cannot happen without this understanding;

- Develop a comprehensive CCI strategy with actionable goals, emphasising cross-departmental collaboration with sectors like tourism; small, medium and micro enterprises and community development and

- Prioritise high-level leadership to champion the sector, with the mayor taking an active role in driving the strategy.

Without bold reform, JAG will remain a stark symbol of missed opportunities and systemic neglect — a painful reminder of Johannesburg’s failure to realise the potential of its cultural wealth.

Mariapaola McGurk is a PhD candidate at Johannesburg Business School, University of Johannesburg, and Natanya Meyer is a professor of SARChI Entrepreneurship Education at the university.