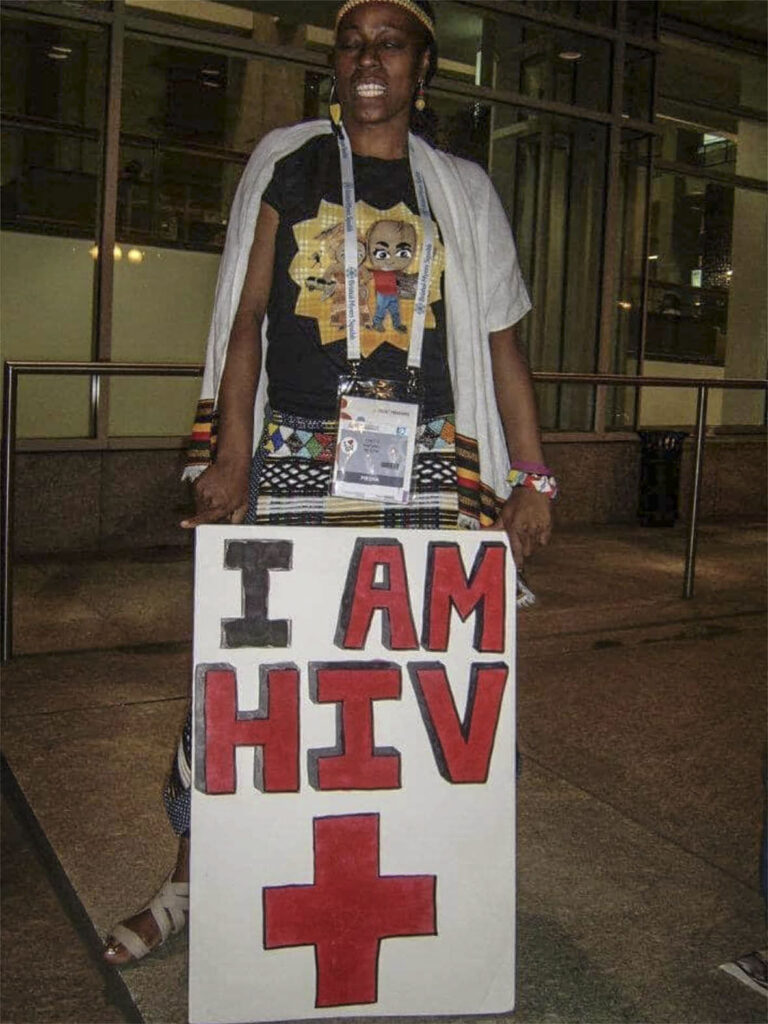

“I’m Yvette and I’m living with HIV,” she declares. “It’s important to me to introduce myself in this way. When I meet someone, I disclose my status first — even before revealing that I’m a mother.”

Two decades ago, when a young, feisty woman from a tiny Limpopo village was diagnosed with HIV, she was forced to reckon with more than just her own mortality. Her biggest fear, greater than the threat to her life HIV posed, was that she wouldn’t be able to provide for her family.

So Yvette Alta Raphael, 25, made a pact with the universe. “If I live”, she vowed, “I won’t withstand injustice.”

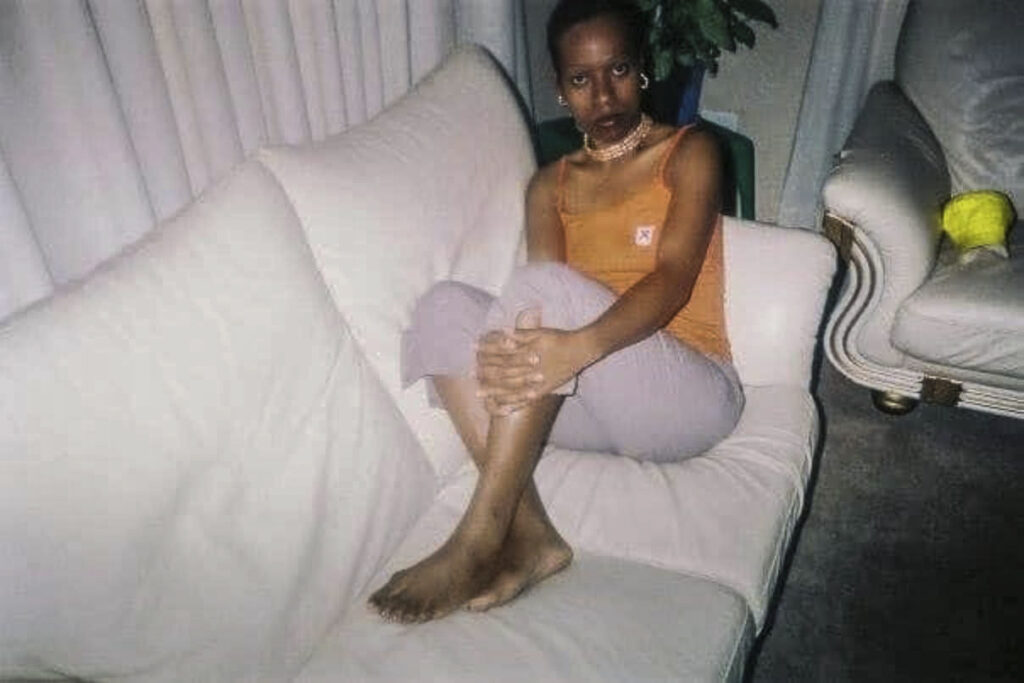

Twenty years later, she has a consciousness of death that most people are fortunate to never have had. But she’s hardly wringing her hands in existential angst. “I’m Yvette and I’m living with HIV,” she declares. “It’s important to me to introduce myself in this way. When I meet someone, I disclose my status first — even before revealing that I’m a mother.”

It’s not a matter of getting an inconvenient fact out of the way, she says. Rather, it’s an embrace of HIV as a part of her identity: “It’s a part of my life and has shaped who I am.”

Raphael gives a wry laugh, rocking back and forth in her chair.

She’s sitting at the kitchen-turned-work table in the Covid makeshift office she created in the lounge of her Midrand home.

The morning sun glows on the pile of files, notebooks and family pictures spread over the table.

“I created a monster,” she scoffs. “I’m always in trouble with the government.”

The horror – and benefit – of being diagnosed with HIV

The personal is political.

This popular slogan, that is credited with birthing a new wave of feminism, was the title of an essay written by Carol Hanisch in 1969. It’s a reminder that women’s struggles are often not the product of individual choices but rather part of a system of patriarchal oppression.

It’s also a call for collective action to what may appear to be intensely personal problems and as relevant to the gendered distribution of domestic chores in a home as it is to how society responds to women with HIV.

Raphael was just 25 years old at the time of her diagnosis. She had a one-year-old baby girl and a good job as a monitoring and evaluation officer at a training organisation in the safety and security industry in Johannesburg.

Her life had just begun to unfold in the most exciting way.

Then, in December 2000, the news came. Raphael was told she had a deadly virus and had three to four years to live.

“It was like having a rug being pulled from beneath me,” she recalls. “I didn’t only have to deal with the medical symptoms of HIV. There was also the stigma.”

Raphael’s diagnosis happened against the background of a politically charged time in South Africa: Former President Thabo Mbeki and his health minister Manto Tshabalala-Msimang’s HIV denialism.

https://bhekisisa.org/article/2016-03-08-00-mbeki-deserves-to-be-condemned-by-history-says-tac/

At the time, being diagnosed with HIV in the country was like a death sentence because Mbeki and Tshabalala-Msimang refused to make antiretroviral drugs (ARVs) — evidence-based treatment that transformed HIV infection from a fatal to chronic condition — available in the public health sector.

https://bhekisisa.org/article/2020-03-25-coronavirus-reporting-journalism-hiv-denialism-evidence-based-response-south-africa-cyril-ramaphosa-thabo-mbeki/

The consequences — in the form of more than 300 000 unnecessary HIV-related deaths between 2000 and 2005, according to a 2008 Harvard University study published in the Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome — were devastating.

Raphael was at the forefront of the fight against the government’s (lack of) treatment policies. And she was determined to survive, determined to be treated fairly everywhere she went.

“When I was diagnosed, I was the first person who tested positive for HIV at my workplace,” she says. “My employer had no HIV policy in place so I created one. It is still being used across the security sector in South Africa.”

But resources and support structures were not readily available then. So Raphael turned to Google, researching the latest trends in HIV treatments: “All my HIV knowledge was self-taught,” she says.

Online, she found a community of people living with HIV in chat rooms. Because it was rare to find people in South Africa on HIV treatment in the early 2000s — the public sector only started to provide ARVs in 2004 — discovering this group of people abroad was an important step in Raphael’s attempt to better understand her diagnosis. She explains: “I was trying to find people like me. As I gathered information, I gathered courage.”

Raphael began working in her own community and soon was at the centre of campaigning against the Mbeki administration’s policies.

She rests her fists on her face and glances at a family picture on her desk.

“My children were the reason I fought,” she says. “They were [and are] my reason for being and deserved a better life.”

And although Raphael’s fight for better public health interventions for people with HIV may have begun as an intensely personal one, it would not have endured if it was just about her.

So her fights multiplied, she says. While her body fought to accept antiretroviral treatment that she accessed through her employer’s medical aid, she was also fighting for society to accept people living with HIV.

Raphael pauses.

“I remember how someone close to me once refused to share a glass with me. It was hurtful. But there were also people who embraced me as their own understanding of the transmission of HIV and the realities of living with it improved.”

Raphael, now in her mid-forties, adjusts the African print hat she’s wearing.

“The fight for access to treatment was larger than myself,” she says. “I had access to ARVs because I had a medical aid. But my friends relying on the public sector didn’t. They were dying right in front of my eyes.

“So for me, this political fight was intensely personal.”

‘Policymakers and Big Pharma are not my friends‘

Raphael would come to raise some of the children of the friends she had lost through the years. She has “10 permanent children”, ranging in age between 13 and 21, she says, and many, many more who come and go.

They had to learn to share me, their mother, but also their home and all that was in it. “I raised them to be better humans,” Raphael says. “I’ve taught them to care.”

And while raising an extraordinary family, Raphael grew into what some describe as “rebellious, but highly effective and passionate” and what she herself dubs “a professional protester, sjambok feminist and hater of trash” HIV advocate.

She’s taken on governments, donors — and civil society. And the issues she fights for are wide-ranging: from increasing the contraceptive choices for women with HIV to sexual harassment to ethical clinical trials, LGBTQI rights and women’s right to choose the form of HIV prevention they use.

When the Smithsonian National Museum of Natural History in Washington DC honoured her as part of an exhibition last year, she was described by Radio 2000 “as a trusted globally renowned advocate on effective and efficient education to the general community regarding new and developing research for medications that treat and/or prevent HIV”.

In the Smithsonian exhibition, beneath her portrait, a quote from her was affixed: “Where the governments see statistics, I see the faces of my friends.”

Raphael has no patience for injustice — or for ego and formal meetings.

“My social construct is about being around people but I don’t wait to gently chide someone,” she says. “I’m very direct.”

And it is exactly that directness that she employs when she speaks about some of the weaknesses of South African civil society’s response to public health policy right now.

“They go sell us out.”

As the founder and head of a non-profit, Advocacy for Prevention of HIV and Aids, herself, Raphael believes that the aims of civil society organisations and individual leaders have been co-opted by government, eroding the efficacy of the sector in its entirety.

For her, activism can only be effective when there’s sufficient distance between activists and those in power. When activists become embedded within elites, or constructing elites within their own spaces, their ability to agitate for change is stymied.

“There has to be a shift,” she says. “Policymakers and pharma are not your friends.”

Learning from her grandmother

A boy walks into Raphael’s lounge, peering closely at the laptop screen on Raphael’s desk.

“Are you on a Zoom call, Mama?” he asks.

Raphael looks at him with make-strict eyes and smiles. “No, I have an actual guest.”

It’s her own childhood that Raphael credits as the starting point of her dedication to feminism and equality. She hails from what she describes as a “community of coloured people at the foot of the Soutpansberg in Limpopo”. There, in Buysdorp, on the R522 road to Louis Trichardt, she was raised by her grandmother alongside six other children.

What she learned from her grandmother in a tiny village continues to inform who she is. “I worked in the fields with my brother and when we went home my brother also did the dishes.”

Raphael watched as her grandmother fought for access to tribal land on behalf of local women. And she’s still inspired by the gains her grandmother won on behalf of disenfranchised women.

Her experience of her grandmother’s parenting, coupled with the activism for land rights she witnessed in the community, taught her that agitating for justice was fundamentally a question of personal morality.

“So what I do today, is in many ways just carrying on with what I saw my grandmother doing.”

Politics, fun and pain

In the years since Raphael was diagnosed with HIV much has changed. Six out of every ten of about eight million people with HIV in South Africa are on antiretroviral treatment — most of them get the drugs for free from government clinics. HIV-related deaths have decreased significantly and biomedical interventions such as the HIV prevention pill, which helps to prevent people from contracting HIV, have come onto the market. There’s also a greater awareness of women’s, human and queer rights in public health spaces.

But there is much that is yet to be done.

“Like everything in South Africa,” Raphael argues, “policy is great but it is the implementation that is lacking.”

But the problem isn’t just government, she warns.

Government’s advantage over a citizenry that is routinely short-changed by poor governance, she says, is a lack of understanding of what our rights are.

“We’re numb to the pain.”

Raphael is ready to take on the government, Big Pharma or the men who dare to deny the violence of patriarchy. Her fights, she says, are strategically placed.

“The thing about being over 40 is you don’t give a fuck what anyone thinks anymore.”

But she’s quick to point out that she’s more than an activist. She also just needs to have fun. So she dabbles in design, selling Pozie items — her own brand of masks, clothes and bucket hats — online.

Online is also where some of her most vocal activism has been done recently. In response to the alarming number of women killed by their intimate partners in South Africa, Raphael was among the first to start the #MenAreTrash campaign. She was also a leader of the #TotalShutdown march, which called on government to respond more decisively to the violence experienced by women.

For Raphael, this is a natural progression of her HIV activism. And so the fights continue.

“No, no, I can’t get tired,” she says. “My fight is so constant, it is my everyday.”

She ponders a little.

“I do get depressed, I get sad. And then I shut off social media and draw my friends — my tribe — closer, refuel and start again closer.”

Finding that comfort, however, is much more difficult in the midst of a new deadly pandemic. And Raphael is acutely aware of how vulnerable she is to a virus that is especially risky for immunocompromised people.

Data from the Western Cape health department shows that people with HIV have a two-to-three-fold increased risk of dying of Covid-19.

Raphael practises strict social distancing to protect herself, but she misses the intimacy of physical contact.

“I’m a hugger. I need hugs.”

But with a small wave of her hand, she says she’s adjusted to the demands of “a crazy time”.

Meanwhile, one of her two Shih Tsu puppies has made off with her shoe.

“Denzil, bring my shoe back!” she shouts.

Carol Hanisch, in that 1969 essay, writes, “There are no personal solutions at this time. There is only collective action for a collective solution.” Yvette Raphael is living – thank science and justice – proof of that.

The personal is especially political.

Additional reporting by Mia Malan. This story was produced by the Bhekisisa Centre for Health Journalism. Sign up for their newsletter.