Happy days: In 2015, then-president Jacob Zuma seemed pleased to receive the exonerating arms deal report from Judges Hendrick Musi (left) and Willie Seriti (right). (Photo: Elmond Jiyane/ GCIS)

A year after their report into the so-called arms deal was set aside, retired judges Willie Seriti and Thekiso Hendrick Musi now face a complaint of gross incompetence for their roles in the tainted investigation.

Earlier this month, public interest organisations Shadow World Investigations and Open Secrets submitted a joint complaint to the judicial conduct committee accusing the pair of failing to discharge their duties as commissioners when they investigated the multibillion-rand arms procurement scandal.

The complaint further suggests that the judges’ actions may amount to criminal conduct, contending that the commission’s final report “materially misled the public”, helping to cover up alleged corruption related to the arms deal.

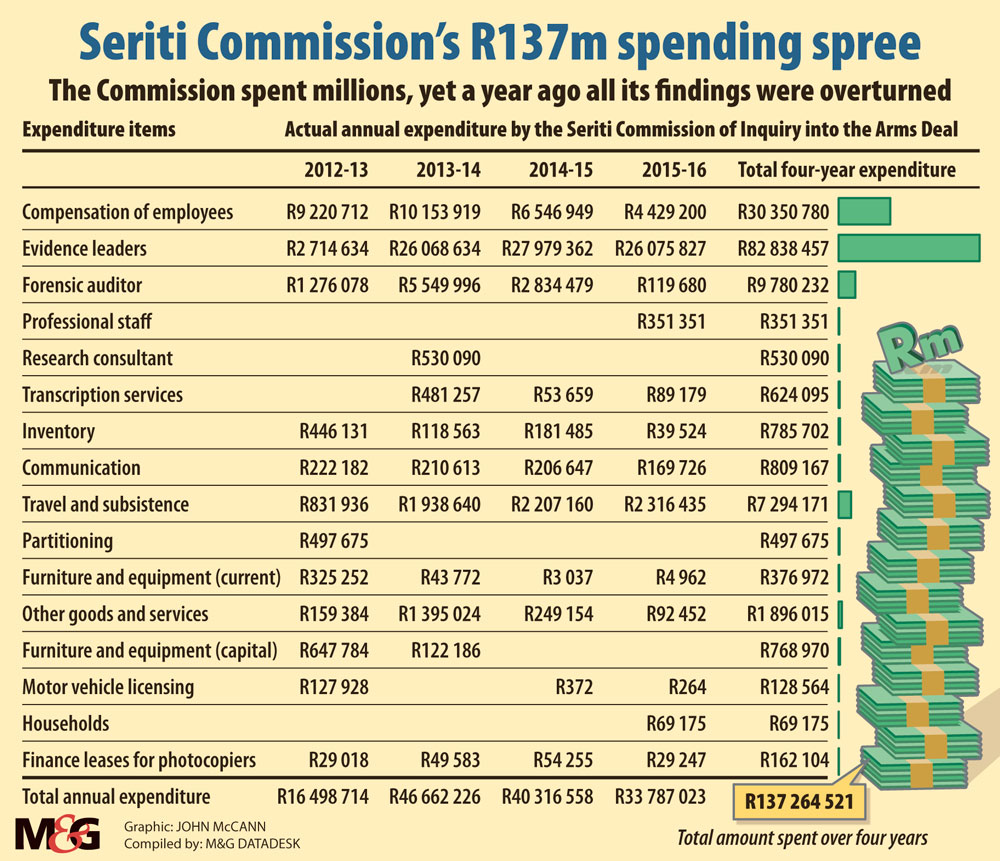

The Seriti commission, appointed by former president Jacob Zuma in 2011, was meant to investigate the government’s controversial purchase of weaponry including corvettes, submarines, light utility helicopters and other light fighter aircraft. The commission initially was costed at R40-million, but, after four years, cost taxpayers R137-million.

The commissioners had more than three shipping containers of evidence at their disposal to trawl through, but the commission eventually concluded that there had been nothing wrong with the deal that cost an estimated R63.5-billion.

The deal was widely criticised because there was no immediate military threat to South Africa. Commentators saw the country’s deepening unemployment crisis as a far more pressing threat at the time.

Some of the equipment purchased through the arms deal, including three submarines, was allegedly non-functional or ineffectively utilised. When the deal was announced, 65 000 new jobs were promised as a result of it. But only 12 965 jobs were ultimately created.

Last year, a scathing high court judgment set aside Seriti’s 767-page report, concluding that the commission “failed manifestly to enquire into key issues as is to be expected of a reasonable commission”. The court case was uncontested.

At the time of the unprecedented judgment, Seriti stood by the report.

In an interview with radio station 702, the retired judge said: “My report is there. That report is close to a thousand pages. That explains exactly what I did, how I did that and why I didn’t do certain things. I cannot add or subtract from that … Every conclusion that we arrived at on all the five or six points of reference, there is a full discussion. And we referred to the evidence of witnesses who came before us.”

But the court judgment, and the recent complaint, both conclude that Seriti and his co-commissioner, Judge Musi, failed to gather and adequately consider evidence relevant to their investigation.

In an affidavit supporting the joint complaint, investigative researcher Paul Holden outlines many perceived holes in the inquiry.

These include the commission’s failure to review more than three million pages of evidence provided to it by the Special Investigating Unit and failure to access the records of criminal proceedings brought against Zuma, Schabir Shaik and Tony Yengeni for matters related to the arms deal. Key witnesses were not cross-examined, while some were never called to give their evidence.

Holden adds: “Conversely, non-critical witnesses were frequently allowed to offer their opinions, and, in certain cases, were actively solicited to give opinions on matters they had no knowledge of.”

At the time, experts, including Holden, refused to appear before the commission protesting its conduct and alleging a cover-up.

In his affidavit, Holden contends that the commission’s failure had two profound implications: First, it brought the judiciary into disrepute. It also imperilled the state’s ability to pursue criminal charges against those implicated in alleged corruption.

“The commission was appointed in 2011. Its findings were published in 2016. It took a further three years for the findings to be set aside in 2019. Cumulatively, the commission has wasted eight valuable years and thus placed a good deal of conduct outside the reach of potential criminal prosecution,” Holden’s affidavit reads.

“The prejudice to the South African public is obvious and profound and can only serve to amplify concerns about the independence and competence of the judiciary and its members.”

Holden contends that the failure of Judges Seriti and Musi to conduct a meaningful investigation into the arms deal constitutes a prima facie case of wilful misconduct or gross negligence.

He adds that there are “clear and worrying signs” that the pair may be guilty of criminal conduct, but says this can only be determined through further investigation.

In their complaint, Shadow World Investigations and Open Secrets ask that the chief justice refers any potential criminal conduct to the appropriate law enforcement authorities.