Rejection: Lawrence Mashiyane, 26, (left) applied for 135 jobs this year but didn’t get one of them, so, rather than be frustrated, he decided to return to university to do his post-graduate degree. (Paul Botes/M&G)

Rising debt, unemployment and hunger — this is the situation for millions of South Africans. The data published by Statistics South Africa paints a bleak picture as the number of unemployed people soars and households tighten their belts even further. The pandemic has only made a bad situation worse.

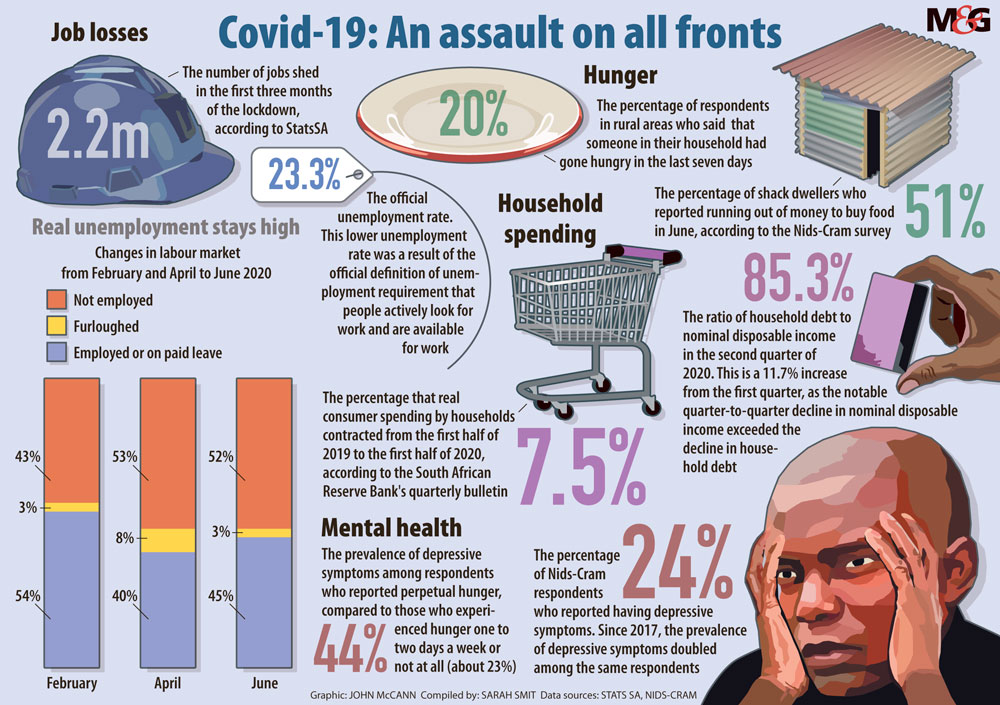

This week, after numerous delays caused by Stats SA having to use new data collection methods in response to Covid-19 restrictions, the organisation released its quarterly labour force survey, which found that 2.2-million jobs were lost in the first three months of the lockdown.

The National Income Dynamics Coronavirus Rapid Mobile Survey (Nids-Cram) found evidence that suggests job losses triggered by the lockdown may be long-lasting.

Households’ debt compared with their disposable income has increased from 73.6% in the first quarter of 2020 to 85.3% in the second quarter, according to South African Reserve Bank’s Quarterly Bulletin.

Duma Gqubule, an economist at the Centre for Economic Development and Transformation, said it is unlikely the country will be able to dig itself out of the hole caused by the recession anytime soon.

“We’re not going to be out of this for a long time — for the next two, three years at minimum — unless there’s a big change of policy from the government,” he told the Mail & Guardian.

“People need to understand the scale of the economic dislocation that’s happening in the country and that it is going to get worse before it gets better. The scarring to society will be difficult to reverse. So the impact of this will be with us for many years to come.”

The reports show that the brunt of the depression is carried by women, the poor and those with less education.

The unemployment rate is highest among people between the ages of 15 and 24 (52.3%), followed by those aged 25 to 34 (28.9%), according to Stats SA’s survey. The latter group experienced the highest quarter to quarter job losses.

Corridor of closed doors

When Lawrence Mashiyane, 26, was growing up, he wanted to be many things: an actor, a geologist, a vet. He eventually set his sights on getting a job as a writer. But his path to employment, as it is for many other young South Africans, is seemingly without end.

After countless rejections and false starts, he returned to academia to try to avoid what feels like an endless corridor of closed doors. This year alone he has applied for 135 jobs.

“I know for a fact that if I wasn’t doing my postgraduate this year, I wouldn’t be doing anything,” he says. “I didn’t want that. I can’t do nothing.”

More than two million jobs were lost between April and June this year.

The expanded unemployment rate, which takes into account the number of discouraged job seekers and people who are not economically active for other reasons, stands at 42%.

On top of this, the national statistical service recorded unprecedented levels of economic inactivity.

A higher rate of inactivity is bad news for a country trying to dig itself out of an unemployment crisis. In September, the International Labour Organisation (ILO) noted that experience from earlier crises shows that activating inactive people is even more difficult than re-employing the unemployed.

This means that higher inactivity rates are likely to make the country’s attempt to boost job recovery more difficult.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Lockdown generation

The second wave of findings from the Nids-Cram report, released on Wednesday, show that from April to June economic inactivity among young people (18 and 29) rose by 2%, but it fell among older workers.

Globally, the Covid-19 economic crisis has hit young people the hardest. In May, an ILO study found that four in 10 young people employed globally were working in hard-hit sectors when the crisis began.

The Stats SA data shows that even when young people remained employed during the lockdown, they were less likely to continue being paid full salaries than older workers.

The ILO has dubbed young people the “lockdown generation”. The organisation also noted that a previous survey of youth and Covid-19 found that more than 50% of young people have become vulnerable to anxiety or depression since the start of the pandemic.

Mpho Dlamini* says that after nine months of being unemployed, she is willing to take any job she can get. The 22-year-old moved back home to Durban after leaving her last job as an online English teacher in Johannesburg.

She says the job search has been taxing. “You could apply for, like, a hundred jobs in a week and not hear back from any of them. Or apply to a hundred jobs [advertised] and get two emails back saying: ‘We got your application, but no thank you.’ ”

Initially, the lockdown gave her “a very small window to breathe, because everything was at a standstill at the time. So if you don’t find a job at this time, it’s kind of to be expected,” Dlamini says.

“But now that things are starting to go back to normal, that same external pressure of: ‘Are you even trying? Are you even applying for jobs? Are you even doing anything?’, is kind of creeping back in.”

Household incomes

The lockdown has also affected how much money households have to spend. According to the Reserve Bank’s Quarterly Bulletin, there was a sharp decline in household consumption expenditure in the second quarter of 2020.

“Spending on durable and semi-durable goods contracted the most, as these goods were mostly classified as nonessential during the lockdown. The real disposable income of households also contracted in the second quarter of 2020, as the compensation of employees declined amid job losses and reduced salary payments during the lockdown,” reads the report.

The real disposable income of households also contracted in the second quarter of 2020, as the compensation of workers declined amid job losses and reduced salary payments because of the economic effect of the lockdown.

Real consumer spending by households contracted by 7.5% from the first half of 2019 to the first half of 2020, consistent with the decline in both consumer confidence and credit extension to households.

Though household debt declined during the same period — for the first time since the third quarter of 2002 — the ratio of household debt to nominal disposable income increased significantly from 73.6% in the first quarter of 2020 to 85.3% in the second quarter.

This means households have more debt than disposable income. Disposable income is decreasing at a higher rate than household debt. People are not buying assets and they are possibly acquiring debt to pay for day to day expenses.

“The pace of recovery to pre-lockdown levels could be slow as households’ ability and willingness to spend have been severely impacted,” the Reserve Bank’s report states.

Going hungry

Different areas in the country seem to be experiencing varying levels of desperation. According to the Nids-Cram report, about 37% of households do not have money for food.

Hunger is highest in rural areas. Although running out of money to buy food is similar across regions and has declined between April and June, experiencing hunger is highest in rural areas.

One in five respondents in rural areas (20%) said that someone in their household has gone hungry in the past seven days compared with 16% in cities and towns and 13% in metro areas.

The Nids-Cram hunger report concludes that social relief measures, such as the special Covid-19 grant, “can only offer limited protection”.

“A strong economy that grows and creates jobs remains essential. It is to be hoped that the gradual lifting of the lockdown and the reopening of the economy will reduce current massive unemployment levels and stimulate the rebuilding of the economy.”

*Not her real name