Municipalities have failed to prioritise the rights of labour tenants and farmworkers

Twenty-six years into democracy, many farm dwellers living on privately owned land still struggle to access water and other basic services.

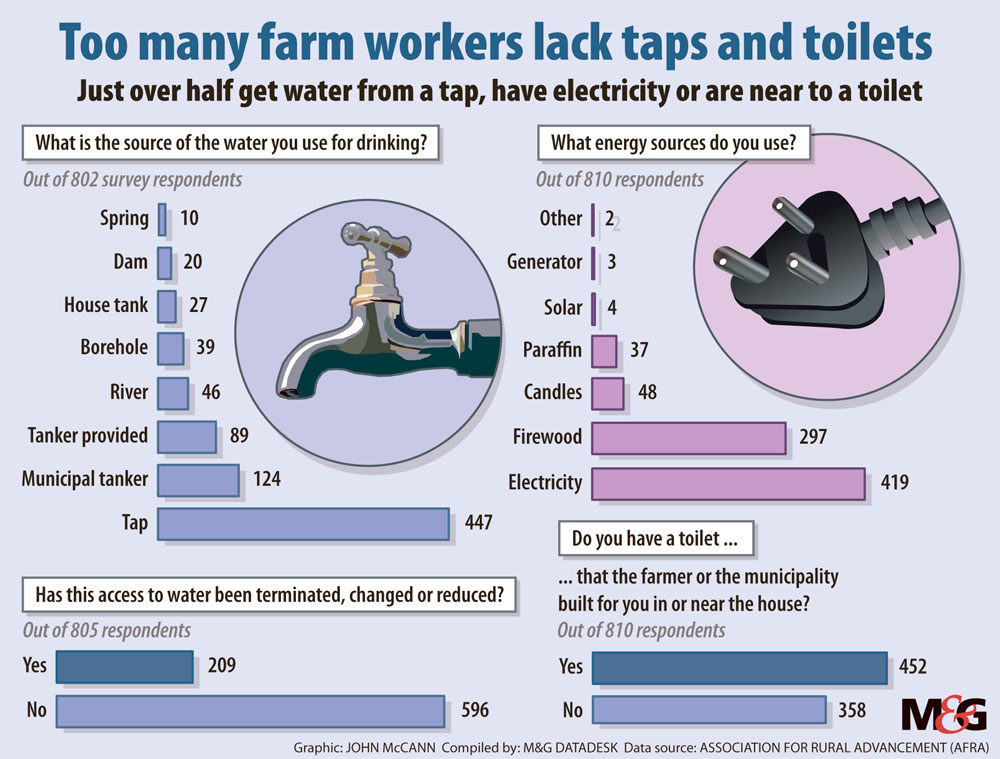

A survey of more than 800 households living on commercial farms in the uMgungundlovu district in KwaZulu-Natal shows that only 447 got their water from a tap and almost half of them did not have a toilet. These households consist of between three and 20 people.

The survey, conducted by the Association for Rural Advancement (Afra) between 2017 and 2018, exposes how both farm owners and municipalities evade responsibility for providing labour tenants, workers and their families with services.

The uMgungundlovu case study is just one example of a wider problem. After lengthy engagements with farm owners and several municipalities, Afra and farm dwellers, assisted by the Legal Resources Centre (LRC), took the fight to claim their rights to essential services to the high court and won.

A recent study, which is part of the “Claiming Water Rights in South Africa” project by the Socio-Economic Rights Institute (Seri), shows how the 2019 court judgment finally gives recourse to farm dwellers ignored by municipalities and living at the mercy of the whims of farm owners.

In 2017, Zabalaza Mshengu and Thabisile Ngema, who both lived on farms in KwaZulu-Natal, approached the Pietermaritzburg high court to get clarity on who bears the obligation — the municipality or farm owners — to ensure farm dwellers have access to basic services.

Section 27 of the constitution provides that “everyone has the right to have access to sufficient water” and obligates the state to “take reasonable legislative and other measures, within its available resources, to achieve the progressive realisation” of the right of access to sufficient water”.

Local government, according to section 152 of the constitution, is tasked with ensuring “the provision of services to communities in a sustainable manner”. Section 153 of the constitution mandates municipalities with structure and managing its administration and planning processes “to give priority to the basic needs of the community”.

Mshengu, who passed away at the age of 104 shortly before the court case was heard, was born on Edmore Farm in Camperdown, KwaZulu-Natal, where he lived as a labour tenant.

According to Mshengu’s affidavit, water is scarce on the farm and the nearest water source — shallow pools in a dried-up stream — is 100m from his family’s home. But, because this water is not suitable for consumption, the family is forced to rely on water sourced from a communal tap more than 500m from the farm.

Collecting water in 25-litre cans is a strenuous task and was impossible for Mshengu in his old age.

Mshengu said in his affidavit that not having a water supply nearby was detrimental to his health and that of his other family members, who had to reuse water to limit their trips to the communal tap.

In his affidavit, Mshengu summarises the plight of labour tenants like himself and his father before him.

“They saw themselves trapped in an exploitative labour system … They were stripped of their rights as owners of the land. They were forced to provide labour for new owners on land that was taken away from them and they were also moved from farm to farm … In short, they lived at the mercy of the new owners,” Mshengu’s affidavit reads.

“Unfortunately, despite the history of farm occupiers and/or labour tenants, it is evident that the local municipalities and district municipalities do not prioritise the rights of these categories of people.”

Ngema lives with her two children on Greenbranch farm in Wartburg in New Hanover. She is a domestic worker.

There is no sanitation system in the Greenbranch settlement, where about 60 people live. There are no household or communal toilets. When the farm dwellers tried to dig pit toilets, they were reportedly told by the farm owner that they were not allowed to and advised to use the sugarcane plantation as a toilet.

According to Mshengu’s affidavit, supported by Ngema, when the Greenbranch occupants make use of the sugarcane plantation, they have to walk through faeces. The sugarcane plantation, which is shared by men, women and children, is not lit and is very dark at night.

Without proper toilets, the women at Greenbranch “suffer great hardship, humiliation and impairment of their dignity”, Mshengu’s affidavit reads. There is no place for them to dispose of their sanitary pads and not enough water for them to wash. There are only two taps on the settlement.

The 2019 judgment declared that the failure of the uMsunduzi local municipality, the uMshwathi local municipality and the uMgungundlovu district municipality to provide the farm dwellers with access to basic sanitation, sufficient water and collection of refuse is inconsistent with various sections of the constitution.

It directed the municipalities to comply with the minimum standards for basic water supply and to prioritise the rights of farm dwellers in their integrated development plans. The court ordered the municipalities to file a report within six months that identifies all farm dwellers living in the area, specify whether they have access to water and what steps the municipality intends to take to ensure that all of them have access to water.

According to the Seri report, however, the deadline to submit these reports lapsed in January and, by May 2020, the municipalities had still not filed their reports.

Spokesperson for uMgungundlovu, Brian Zuma, said the municipality is consulting with its attorneys to find “a way forward for council to make further resolutions to meet requirements as ordered by the court”.

He added that the municipality is constructing 362 toilets on farms for use by farm dwellers and farm labour tenants. Other farms were supplied with water tanks and others recently had boreholes constructed for access to clean water, Zuma said.

The other two municipalities had not responded to requests for comment at the time of publication.

According to the Seri report, uMsunduzi launched an application to appeal the judgment. Despite this, Afra and LRC are confident that the municipalities intend to comply with the court order.

The judgment has far-reaching implications for farm dwellers seeking to claim their water rights, the Seri report notes.

“Firstly, after years of careful engagement with several municipalities and a range of farm owners, Afra and the farm dwellers they work with are now being taken seriously.”

It also stands to ensure there is greater uniformity in water provision on farms, so that farm dwellers no longer have to depend so heavily on their employers or landlords.

The report adds: “The judgment has been favourably received by other municipalities in the area and further afield [that] seek to understand its implications for water services provision in their own jurisdictions.”