A reclining man with a horn mask was copied by Agnes Schulz in Zimbabwe in 1929. (Frobenius Institute)

The Centre Pompidou in Paris held an exhibition in 2019 that explored how prehistoric art had influenced modern art. It included copies of rock paintings made by artists in Southern Africa on expedition with German archaeologist Leo Frobenius in 1928 and 1929.

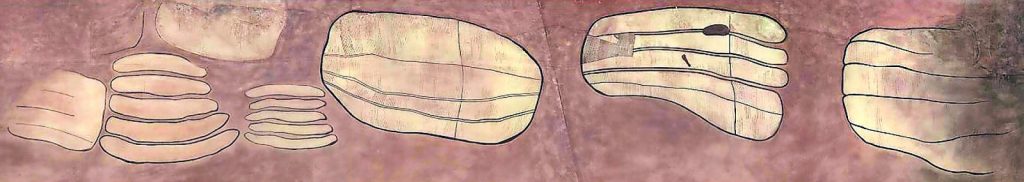

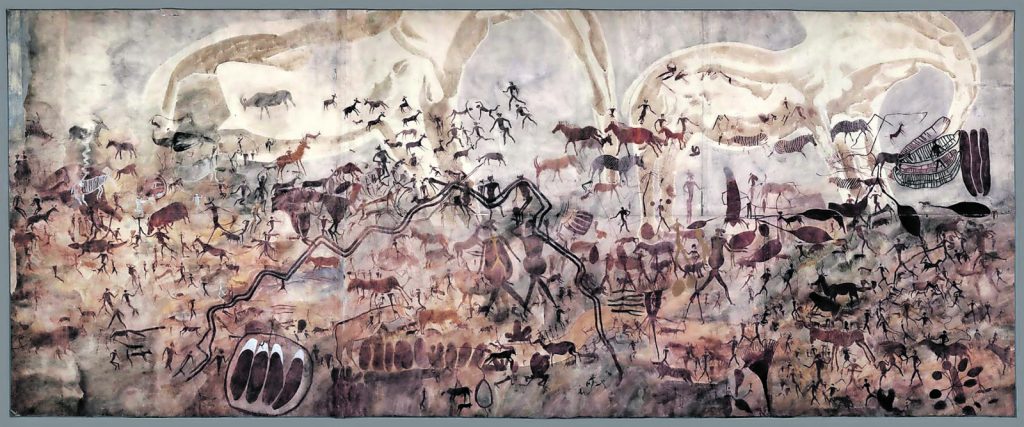

Pompidou curator Remi Labrusse, in a video by French broadcaster RFI, discusses the seven-metre Mutoko copy and a 1.3-metre copy from Makumbe. He says the Makumbe is “extremely abstract” while the Mutoko is “completely figurative because it shows something like a hunt. It’s full of animals, all sorts of hunters, men and women.”

The Mutoko and Makumbe copies were shown at the Pompidou alongside one another, just as they had been exhibited 82 years earlier in 1937 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art (MoMA).

The Frobenius tracings nourished the abstraction-figuration debate at the time, says Labrusse.

MoMA featured 157 facsimiles, including 38 from Southern Africa. These were juxtaposed with artworks by 12 modern painters, including Jean Arp, Paul Klee and Joan Miró, the aim being to “convince a sceptical public that all those strange new forms in modern painting could be traced back to palaeolithic times — to humankind’s first picture-making”, museum director Alfred Barr wrote in the catalogue.

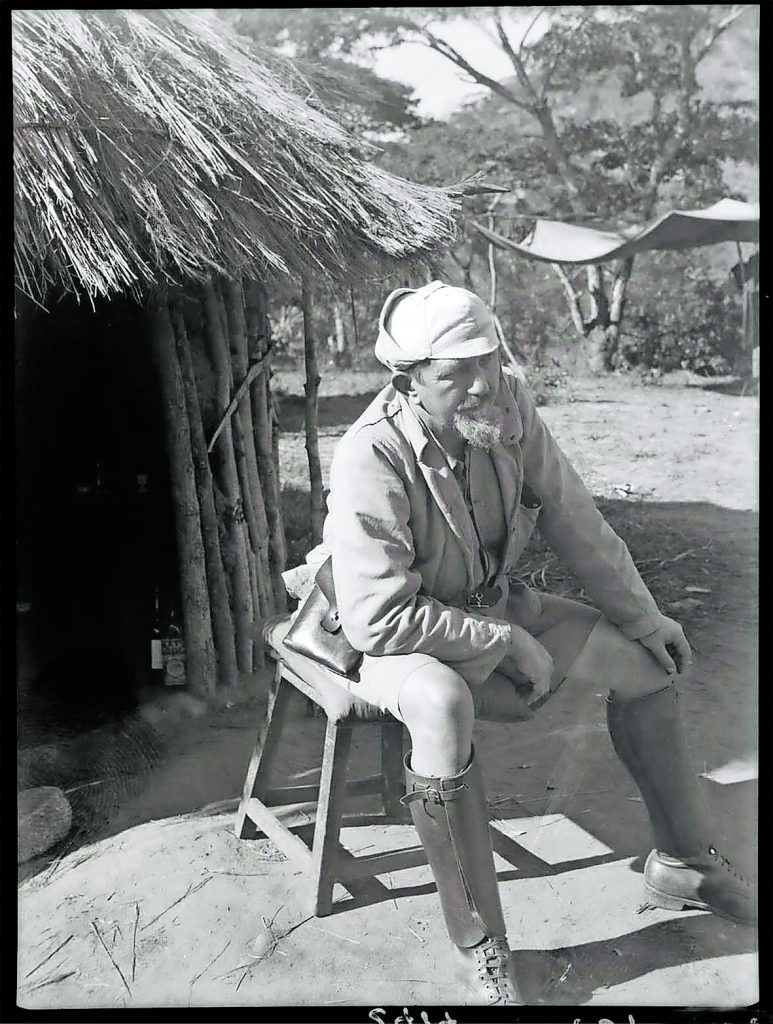

Explorer: German archaeologist Leo Frobenius in Zimbabwe in the late 1920s. (Frobenius Institute)

Explorer: German archaeologist Leo Frobenius in Zimbabwe in the late 1920s. (Frobenius Institute)

“That an institution devoted to the most recent in art should concern itself with the most ancient may seem something of a paradox, but the art of the 20th century has already come under the influence of the great tradition of prehistoric mural art,” Barr wrote. “The formal elegance of the Altamira bison; the grandeur of outline in the Norwegian rock engravings of bear, elk and whale; the cornucopian fecundity of Rhodesian animal landscapes; the kinetic fury of the East Spanish huntsmen; the spontaneous ease with which the South African draughtsmen mastered the difficult silhouettes of moving creatures: these are achievements which living artists and many others who are interested in living art have admired.”

The collection subsequently went on a two-year tour of 32 US cities.

Art historian Elke Seibert says in a 2019 essay, The First Surrealists Were Cavemen, that the exhibition inspired a group known as the American Abstract Artists, who appropriated what they saw, giving rise to American abstractionism.

“Prehistoric cave pictures inspired the genesis of contemporary art,” Siebert writes, “not only on account of the previously unimagined time-span it traversed but also because of the magical discovery of incipient human creativity.”

The Frobenius Institute, established in 1925, was flattened during the bombing of Frankfurt during World War II. But notwithstanding the bombing, the collection, which Frobenius began in 1898, and which includes material from tours after his death to Asia, Australia, Europe, North and South America and Oceania, now has 8 300 rock art copies, 134 000 books and 60 000 photos.

After Frobenius’s death in 1938 the world moved on. Reproductions, in the age of colour photography, became passé.

But some of the rock art collection moved for safekeeping before World War II was rediscovered in a damp basement by institute staff in 2007.

Reproductions: Elisabeth Mannsfield was one of three women with Frobenius who made copies of rock art in Southern Africa.

Reproductions: Elisabeth Mannsfield was one of three women with Frobenius who made copies of rock art in Southern Africa.

It is now enjoying a renaissance, being shown at numerous galleries and museums, the Centre Pompidou being a case in point, as well as in Berlin, Frankfurt am Main, Dakar, Mexico-City and the Paul Klee Zentrum in Bern.

Richard Kuba, the head of rock art at the Frobenius Institute, would love to see the material exhibited in Southern Africa.

But this would amount, in the case of the Southern African material, to bringing coals to Newcastle, since a significant number — 479 — are already here, as they have been for nearly a century now.

The copies may be beautiful, but how accurate are they? The question is not easily answered. With few exceptions, there have been no comparisons of the authentic art with the copies, nor what the artists made in the field with those sent to South Africa. Making in situ comparisons now is problematic because most have deteriorated in the past century.

As art historian Pippa Skotnes has pointed out, even the notion of what is original seems antithetical to the way the paintings were made. They “were never unified, whole, complete works of art and were continuously in the process of being created as they were being reabsorbed into the unpainted world”.

There were just two showings in South Africa after the expedition completed its work, in Pretoria and Johannesburg, in August and December 1929, respectively.

Dorothea Bleek, a leading rock art authority, viewed the collection in Pretoria. Petro Keene notes in her thesis that Bleek wrote to Dr L Gill, the director of the South African Museum (later Iziko) saying the paintings “may be inaccurate, were too colourful and that the sum of money offered to Frobenius [£5 000 pounds] was too high … it must be just a gift, not a purchase”.

The Makumbe copy was exhibited at the Pompidou in Paris in 2019. (Frobenius Institute)

The Makumbe copy was exhibited at the Pompidou in Paris in 2019. (Frobenius Institute)

But others who have compared the copies with the “originals”, see them to closely approximate the authentic. Justine Wintjes, in a 2016 PhD study, Archaeology and Visuality, focused on the trip the three women artists, Elizabeth Mannsfeld, Maria Weyersberg and Agnes Schulz, made to northern Natal, to Cinyati, now eBusingatha.

Wintjes noted the difficulties in getting to these sites, their transport including train, bus, car, horse and foot. The Didima site in the Drakensberg, for instance, took 11 hours to reach on horseback.

Cinyati had been subject to vandalism, sanctioned removal of some rock art in 1947 and natural collapse of part of the shelter in 1990. Wintjes used recordings of the art, including by the three artists, to digitally reconstruct what the shelter had looked before the removals and collapse.

Wintjes says the artists “produced copies that accurately reflect many aspects of the originals … the copyists were highly accurate, comprehensive and sensitive recorders of unfamiliar imagery”.

Asked about this, Kuba said: “I cannot say much about accuracy, but in the few cases I cross-checked with the originals, I found them quite impressive for the time. The [artists] usually made 1:1 sketches to get the dimensions right and test the colours.

“Some of the women artists acquired tremendous experience, such as Agnes Schulz, who produced over 700 copies on three continents. However, translation from 3D to 2D always implies choices, which not everybody would endorse.”

Kuba said when the copies were found in 2007 in the basement “some people in the institute had even suggested, as they are not regarded as ‘proper’ scientific documentation, that we throw them away”.

Mannsfeld, returned after the expedition to live in then Rhodesia. She spent the rest of her career in Sailsbury/Harare, recording rock art for the Queen Victoria Museum, now the Zimbabwean Museum of Human Sciences. She married a local man, adopting the surname Goodall.

Archaeologist Peter Garlake sings her praises in The Hunter’s Vision: The Prehistoric Art of Zimbabwe, saying her main concern was to reproduce the aesthetic qualities of the art. “She was happy to adjust compositions to strengthen their effect and to transpose the thick, dry, opaque pigments of the [original] artist into the much more fluid and transparent medium of watercolour.

“Despite the primitive materials she had to use in tracing and the techniques these imposed, her copies succeed in capturing the character of the art in a different medium while retaining accuracy, precision and detail more successfully than any other copyist, copying system or photography.”

Laura de Harde, who completed a PhD, A Quiet Contribution to Rock Art Research in Southern Africa, 2019, on Goodall, writes that in her repeated engagement with a site known as Diana’s Vow, Goodall did more than merely copy the paintings.

“The creative research methods that she employed illuminate and capture complexities and sometimes overlooked aspects of the paintings, making them visible through her careful visual engagement.”

American archaeologist Anne Stoll, who is working on a biography of Goodall, and her photographer husband George, have made four trips to Zimbabwe since 2013.

In 2019 the Stolls photographed 50 images in situ of the 94 copies Goodall published in 1959. These are both using high-definition cameras and D-Stretch, a technology which helps make faint rock art images visible, meaning Stoll can see images not visible to Goodall.

Stoll says her impression is that omissions may have to do with how the copy was composed and that “noise”, such as faint background, may have purposely been ignored.

She cites an example from Glen Norah, known as the crocodile site, where Goodall omitted a figure from her copy.

Although the copies are remarkably accurate as to scale and everything else, “absolute accuracy, if indeed it was the goal, was never — could never be — achieved”, says Stoll. “But more to the point, the copies are wonderful. And why not eliminate the noise? I have never seen the artists’ copies as ‘inferior’. They are different from what I can see when enhancing a photo taken at the site. But they are not inferior! They bring the art to the people. An exhibit of both should be the goal, in my opinion.”

Covid-19 thwarted planned trips to Zimbabwe to visit the sites which inspired the facsimiles that delighted art lovers in Europe and the US. In June 2022 we managed a 12-day trip.

Mutoko and Makumbe were top of my list, but the latter is covered in soot. The Zimfieldguide website says this “is a good example of how easily this precious and unique rock art is destroyed. Makumbe cave is now completely ruined with smoke damage; once considered one of the best sites in Zimbabwe.”

So bad is the damage that the site has been delisted as a national monument by the National Museums and Monuments of Zimbabwe.

The Mutoko site is a few hours’ drive northeast of capital Harare, near a small town of the same name. The cave, now known as Ruchera, is set in sweeping, bulbous, bare-faced mountains which dominate the terrain here, as they do for much of the Zimbabwe landscape.

The cave is a few kilometres off a dirt road, in a village. There is a place to park and a short, steep climb up a rock-strewn incline to the cave, an expansive semi-circular overhang with a dome-shaped ceiling.

There is a low fence with an equally-low locked gate, but with the wire on the gate mostly absent, providing at best notional protection. Ahead, looming up on the rock walls were the out-sized elephants, the mainstay of Joachim Lutz’s rendition, which dominate the art below.

His copy includes at least 200 separate images, some of which I could make out. I could not see the splendid colours he came up with. Close scrutiny later of one of my photos perhaps suggests the presence of these colours.

There were also, apparently quite recent, cases of graffiti, deep scratchings of figures into the artwork.

What particularly impressed me with the Lutz copy at Iziko was how networks of connected pods pulled the story together. Another defining element is the double zig-zag line that cuts across maybe a quarter or a third of the painting.

The double line was visible in a relatively small section of the wide expanse of the panel, but I could not make out the connected vines and pods, including a nine-lobed plant in the bottom right-hand corner.

But in the Ruchera images Anne Stoll sent me, the plant is clearly there.

“Lutz’s image is just stunning. I sure wish it did look like this! There are pieces of it still remaining,” she said.

“If you orient using the zebras and the elephant’s leg, you can just make out some of what was on the Lutz painting. The tall man standing on the left is there, but there are other figures to his right, not included in the painting. I don’t think any of this was added later.”

Stoll says she thinks Lutz painted the elements he wanted to paint, adding that he too cleaned up the background of noisy areas.

“He added and omitted and believed, rightly for almost 100 years (!) that nobody would ever check. I love his painting but it just does not show what the San originally painted there.”

We also visited Enanke in the Matopos, a cave that pundits agree has the most impressive example of formlings. Formlings are typically ovoid shaped, but the main Enanke formlings are rectangular.

The Enanke campsite in the Matopos gets just two parties of visitors on average a month, only one of whom will make the scenic, 6km hike to the cave. The route is signposted, but it would still be easy to get lost; a guide is highly recommended.

Like others we saw in Zimbabwe, Enanke is a large semicircle with a dome-shaped roof in an overhang. Centre-left is a line of coloured formlings — red, orange and yellow. White, cloud-like ovoids hover above and below. Three giraffes are in relief against the rectangles, they are part of the formlings and emerging from them at the same time. A large giraffe stands to the one side and an even larger one above, disconnected from all below.

Two strange figures, which I have not seen in other paintings, lurk alien-like above a large ovoid to the one side, above the others.

Adjoining is an out-sized man, perhaps propped up by two tall trees that may even be part of him. He stands in a sea of flecks in figure-of-eight formation.

The paintings are in good condition, right down to tiny dots lining part of the formlings.

Maria Weyersberg painted the Frobenius copy in 1929. Titled Inanke (Mandjendje), it is close to what can be seen today, although the colours are a little different.

A morass of figures, animal and human, which blend into one another below, are not shown in the Weyersberg rendition. She apparently made a decision to leave out this part of the panel, but in my view her copy does artistic justice to the main features of the panel, even though she has not copied it exactly in its entirety.

The Mutoko. (Frobenius Institute)

The Mutoko. (Frobenius Institute)

There may be little doubt that the renditions by the expedition artists show brighter colours and luminosity than can be seen in situ today. Did they exaggerate what they saw?

Harald and Shirley-Anne Pager created a similar vibrancy in their work in the Didima Gorge in the Drakensberg in the 1970s, by taking large format black-and-white photographs, and then adding colour sampled from the rock wall, to recreate the former glory. This method has also been criticised for producing too colourful results.

In just one case, having spent several days in the Didima area over two trips, did I see such luminosity, perhaps what viewers would have seen when at their most splendid. The images of eland seemed to glow.

The time of the art facsimile passed, art historian Westrey Page wrote in Translating Prehistory: Empathy and Rock Painting Facsimiles in the New York Museum of Modern Art (2021), “at least temporarily, as colour photography meant that artist’s copies were seen to be inferior to what the new technology offered”.

Westrey says Frobenius saw that it was through evoking the intuitive listener, by engaging their soulful substance, that the story became alive and comprehensible. She quotes Frobenius: “The fact remains that every picture, whether carved into the rock by a prehistoric man, drawn by a child or painted by a Raphael, is alive with a certain definite spirit, a spirit with which the facsimile must be infused.”

Frobenius, says Westrey, “attacked the ‘mechanistic’ (as opposed to intuitive) culture he observed in the contemporary Western world and likened photography to a dry and all-too rational tool for objects that were imbued with a powerful spirit”.

“The predominantly female copyists working for Frobenius were thus to be precise but intuitive beholders, approaching images to enliven them once again through a kind of co-experience.” In this way they would capture the “spirit” of the images, something colour photography was not capable of doing.

Frobenius got some things wrong, but he was right in at least one thing, creating the space for the artists to create beautiful copies of what they saw even while what they copied was already in a state of deterioration. The results are transcendental.

Copies are not given the status of masterpieces. But in this case there is a clear acknowledgement that the works are copies. There is also homage to magnificence, making the best of these works masterpieces in their own right.

This story was made possible by the M&G Guardians Project in partnership with the Adamela Trust.

To read the first two parts of this trilogy, click here.