South Africa’s social security system is aimed to assist the most indigent in society and is of no benefit to the middle class who must provide their benefits via group life or own insurance provisions.

South Africa’s social security system is aimed to assist the most indigent in society and is of no benefit to the middle class who must provide their benefits via group life or own insurance provisions. South Africa’s disability pension for example only pays an amount of R1 860 per month for households earning less than R13 020 per month. This is likely to continue for the foreseeable future because of our economic situation, corruption and the effects of the current pandemic.

Research by John Simpson, former director of the University of Cape Town’s Unilever Institute of Strategic Marketing, defined middle-class South Africans as people earning more than R23 250 per month, although salaries have shrunk because of the pandemic, according to the BankservAfrica TakeHomePay Index.

Nevertheless, these individuals must make provision for their social security during their working lives in the areas of personal risk and retirement lest they join the ranks of the indigent.

It is a “cultural norm” for many black South African parents to rely on their children for financial support but viewed from the perspective of their children, a dependent parent or family member’s requirement of support is regarded euphemistically as a “black tax”: the idea that the parents’ sacrifice during and after apartheid entitle them to the support of their now upwardly mobile children.

Perhaps it is a western idea but from a financial planning point of view, it is ideal that people should strive to insure, invest and obtain self-sufficiency during their working lives and not be a burden to their children.

Certainly, Generation X, those born in the 1980s, should not be passing on this burden to their children and should be seeking the services of a financial planner to achieve financial well-being.

The journey towards self-sufficiency: disability and life cover

The 2019 Insurance Gap Report by the Association for Savings and Investments South Africa (Asisa) calculated that South Africans are doing poorly in terms of self-sufficiency as in 2019 the total life insurance shortfall stood at R34.7 trillion.

The study found that if an earner dies, the average South African family will need a life cover pay-out of at least R1.6 million to sustain the standard of living. The average South African earner had just R600 000 of life cover, however.

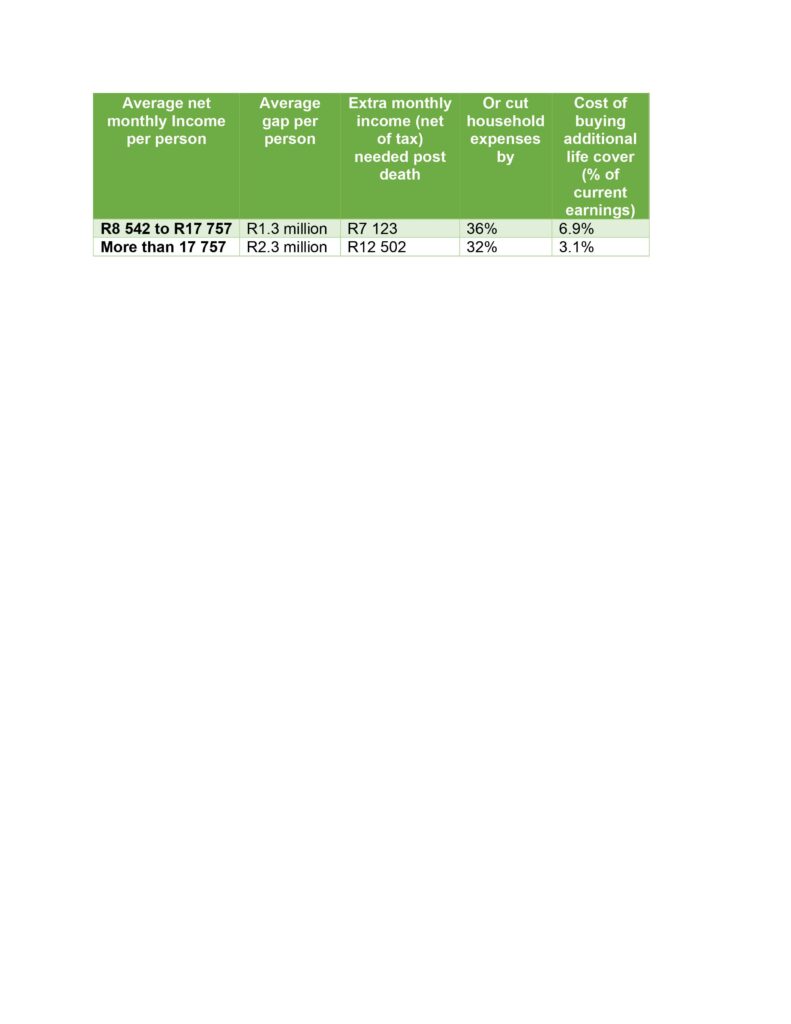

The following table breaks down the difference in life insurance per earnings category and shows how much households will have to cut their monthly income spending in each income bracket or raise earnings should an income earner die.

According to the Asisa report, the average South African earner would have had to provide R2.3 million for disability cover to support his or her family to sustain their standard of living in the event of a disability. But, the fact is that at the end of 2018, the average South African earner had disability cover in place of only R1.1 million.

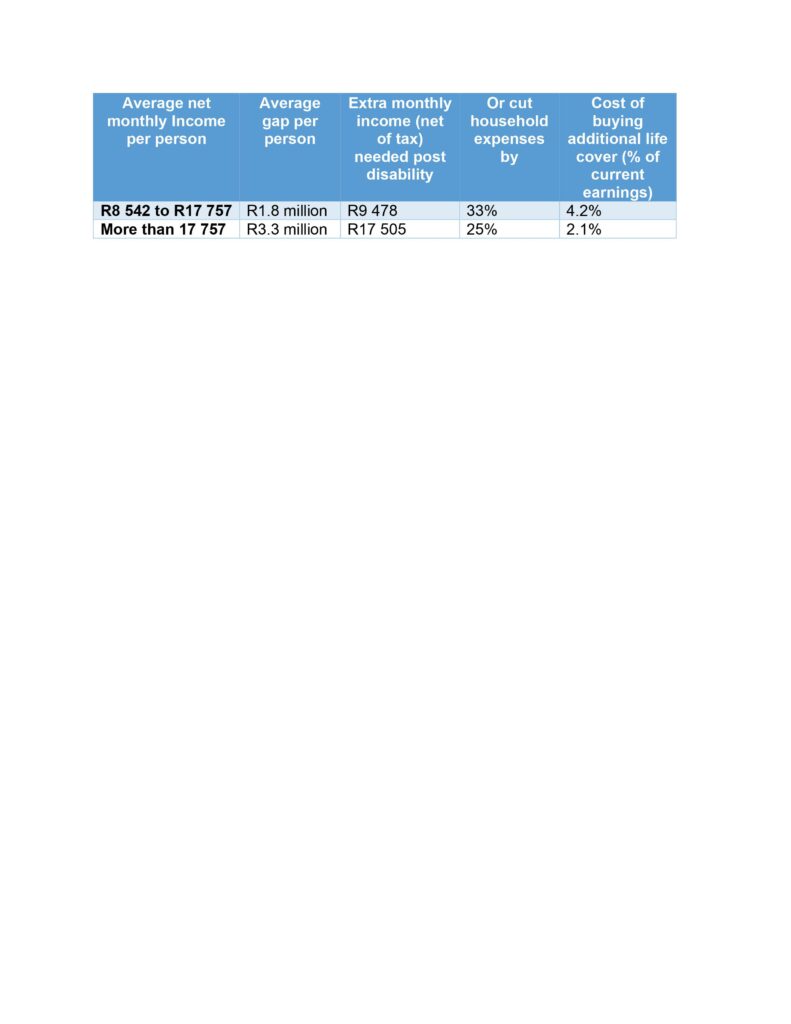

The following table breaks down the difference in disability insurance per earnings category (middle-class and upper) and shows how much households will have to cut their monthly income spending in each income bracket or raise earnings should one of the earners of the household become disabled.

Whose advice should you seek and what should you be asking about?

The advice of an independent financial adviser who has contracts with all major insurance companies in South Africa should be obtained. Tied agents are often restricted or incentivised to sell the products of their employers and may not be able to provide objective advice.

The cover should preferably be purchased after a comparison of the long-term costs and benefits of fully underwritten cover quoted by various insurance companies.

Many South Africans buy cover from direct insurers who conveniently provide cover telephonically, free of a medical exam on the understanding that underwriting could be done at claims stage. In other words, only when you are disabled will you know for sure whether your policy will pay out. This could lead to many more claims being denied as a result of a client simply forgetting to disclose a material fact.

The law permits an insurer to repudiate (i.e. decline a claim) if a client failed to declare a material fact, whether or not he or she did so knowingly. The devastating consequences of claims being repudiated at the claims stage can be avoided by buying fully underwritten cover with an adviser who becomes familiar with your medical and financial history.

How much cover should one buy?

The basic premise of planning for disability is to either have sufficient assets or an insurance policy or a combination of both to provide sufficient capital which when invested, would provide an income for a period escalating at inflation.

Many mathematical models are automated and can be obtained online but this exercise should preferably be done via a consultation with a financial planner. A disability policy might provide an income instead of a lump sum.

A simple method is to determine how much the lump sum should be to take the annual income required and divide it by 6%. Thus, if one’s shortfall is R20 000 per month the amount of capital required in today’s value is R4 million. This is the amount of cover required to provide a level income (non escalating).

The policy should have an option for cover to escalate with inflation for the term required. Asisa calculates that the cost of buying the required cover would be between 3% and 6% of earnings — presumably, they refer to underwritten cover which would provide much wider cover than the direct cover.

As Winston Churchill, who was well experienced in global times of strife, once said: “If I had my way, I would write the word ‘insure’ over every door of every cottage and upon the blotting pad of every public man, because I am convinced that, for sacrifices that are conceivably small, families can be secured against catastrophes which otherwise would smash them forever.”

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.