Qualifying electricians test how a solar panel works during the practical part of the training at Nkangala's Top of the World Training Centre in Emalahleni. (Photo by ROBERTA CIUCCIO/AFP via Getty Images)

Recent work at the think tank ODI sheds light on how governments, multilateral development banks and private sector investors might navigate the energy transition in politically savvy ways to align with climate change goals. This is important regarding South Africa’s 29 May elections because national development priorities centre on energy and unemployment: two key delivery priorities of the country’s Just Energy Transition Partnership (JETP).

Yet, for a long time the value chain around Eskom has been a significant source of rents for some powerful actors connected to certain ANC factions, including those associated with the previous president, Jacob Zuma. Today, however, President Cyril Ramaphosa, heads a different political faction in the ANC, with fewer vested interests in fossil fuels.

Moreover, Eskom is in crisis: South Africa has endured severe power outages over the past couple of years. As the outages and related costs rose, so did Eskom’s debt burden, with increasingly dire effects on the economy and the government’s fiscal position. This abysmal performance of the electricity system and its negative effects on the broader economy are hurting the ANC’s track record in office.

Although there may be both elite and broad-based interests behind an energy transition, there are powerful opponents. Some in the ANC continue to campaign for the full development of fossil fuels (mainly coal) and fearmonger job losses associated with the inevitable energy transition.

Moreover, dispersed power from contrary political factions in the ANC present a challenge to Ramaposa’s position and to a rapid and just energy transition. For example, Minister of Mineral Resources and Energy Gwede Mantashe has proposed extending the lives of specific coal plants by 10 years in the Integrated Resource Plan (2031–2050). He also publicly contradicted the JETP, saying that, “given the abundance of coal resources in the country”, it would continue to play a “significant role in electricity generation” until 2050.

The Integrated Resource Plan can be interpreted as an internal challenge to the JETP and symbolic of Ramaphosa’s inability to secure political consensus on the energy transition even from senior members of his own political party.

Reconciling these competing positions within his own party, and the broader political landscape will only become more difficult should the ANC need to enter into a coalition government after the elections.

Ironically, former president Jacob Zuma, who many hold responsible for Eskom’s poor performance, is now campaigning for the newly established uMkhonto weSizwe party, further dampening the ANC’s electoral prospects.

This election is seen by many as the country’s most important one since the fall of apartheid in 1994. But the balancing act of implementing a just energy transition in one of the most unequal countries in the world might become even more salient in future elections.

Against this background, mining communities and trade unions are important players with potential veto power, and the JETP is being designed with a view to compensating, or at least placating them.

South Africa’s JETP Investment Plan emphasises restorative justice for coal communities in the transition away from coal as the country’s main source of power. It highlights that a core aim of the energy transition is to redress high levels of energy insecurity and poverty and creating quality jobs in new sectors such as electric vehicles, green hydrogen, renewable energy and manufacturing. Most of the dedicated just transition investments in the JETP Investment Plan are accordingly committed to regions where coal mines, and coal-fired power plants are concentrated.

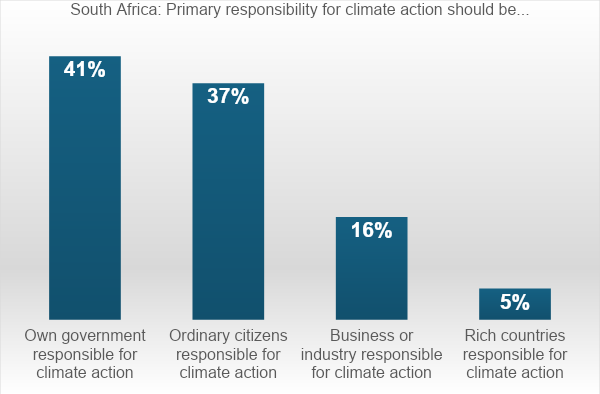

It is not only organised interest groups that want the government to take the lead in managing a just energy transition. Citizens want the government to take the lead on limiting climate change and reduce its impacts (41%), and implementing a just energy transition is a crucial aspect of this. In contrast, only a minority of South Africans see rich or developed countries (5%) as primarily responsible for taking climate action in the country.

Figure 1: South Africans sentiment on who is responsible for climate action (Source: Data from Afrobarometer).

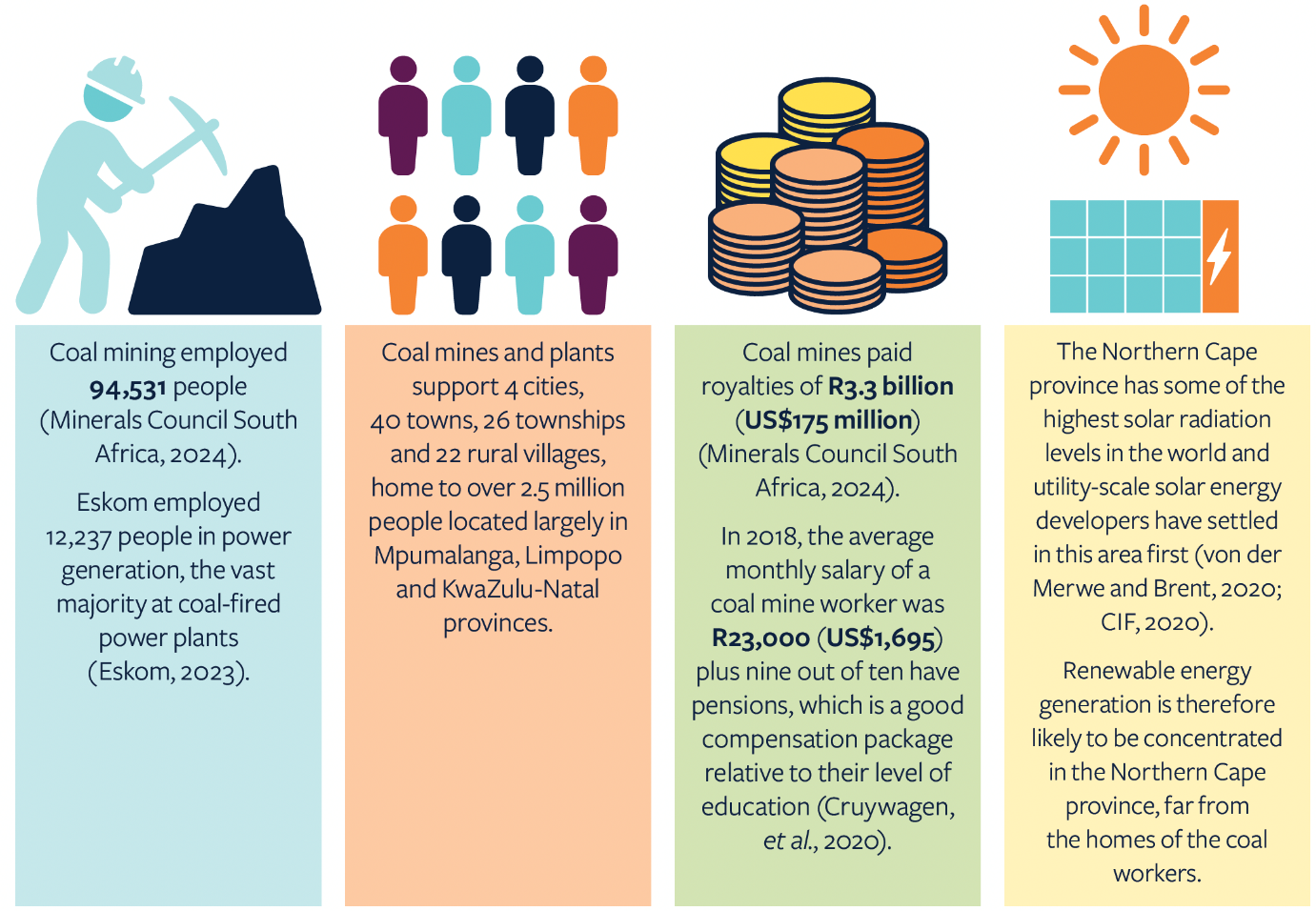

Internationally, this sentiment on responsibility attributed to the South African government strongly aligns with the climate finance arrangement of the Just Energy Transition Partnership. International donors such as the United States, United Kingdom and the Netherlands have committed to $11.9 billion in financing to support the government’s plans for an energy transition that can take advantage of opportunities created while also putting in place local economic development safeguards to minimise its effects on people affected by the transition. This is particularly important in the South African context because of how many people will be directly and indirectly affected by coal mine closures

Figure 2: Statistics relevant to a just energy transition in South Africa in 2023 (source: ODI Working Paper: Putting the ‘just’ in Just Energy Transition Partnerships)

As South Africa stands at the energy transition crossroads, it is critically important that it does not pursue a self-harming developmental pathway through continued fossil fuel development. It should rather take every opportunity to shift development pathways to embrace opportunities presented by the energy transition and reduce the vulnerability of its people and energy systems.

Securing bottom-up buy-in from the wide range of stakeholders affected by the energy transition will be increasingly important to election cycles as climate action progresses. This includes those with strong stakes in the incumbent system, workers who may see their jobs at risk and low-income groups. Political fearmongering that aims to take advantage of these groups’ concerns will have to be managed.

As only 43% of South Africans are aware of human-caused climate change, according to recent survey data, there is danger that uninformed voters, the eighth lowest score across a sample of 39 African countries, can be more easily swayed away from progress on climate action.

There are inevitably winners and losers in any energy transition, which makes it both highly politicised and contested. We will have to wait and see if this election will advance or set back the JETP through its selection of those in power.

Dr Nick Simpson is a senior research fellow in the Climate and Sustainability team at ODI. His research focuses on how we can best respond to climate change with special interest in climate-resilient development pathways for Africa.

Dr Matthias Krönke is a researcher at Afrobarometer and a visiting fellow at the London School of Economics and Political Science. His research focuses on how political parties contribute to democracy and deal with major challenges such as climate change.