President Cyril Ramaphosa signed the climate change bill into law last month.

The recently signed climate change bill is a progressive step not just for South Africa but the continent as a whole, experts have said.

President Cyril Ramaphosa signed the bill into law in July after nearly 10 years of discussions and seven years after the first draft was published. It charts the way for South Africa to deal with the climate crisis, aligns policy action and aims to ensure that every organ of state takes the necessary steps to deal with the effects of climate change.

The new law is a positive step because not many other African countries have legislation to deal with climate change, said Kulthoum Omari-Motsumi, a member of the African Group of Negotiators.

“It’s something that I think South Africa is leading, and a few other countries I know they’ve got, but at least it’s quite progressive, and it’s something that South Africa should be commended for,” Omari-Motsumi told the Mail & Guardian on the sidelines of a training workshop in Kenya last week for journalists.

The new legislation deals with, among other things, South Africa’s ability and capacity to over time reduce greenhouse gas emissions and build climate resilience, while minimising the risk of job losses and promoting opportunities for new jobs.

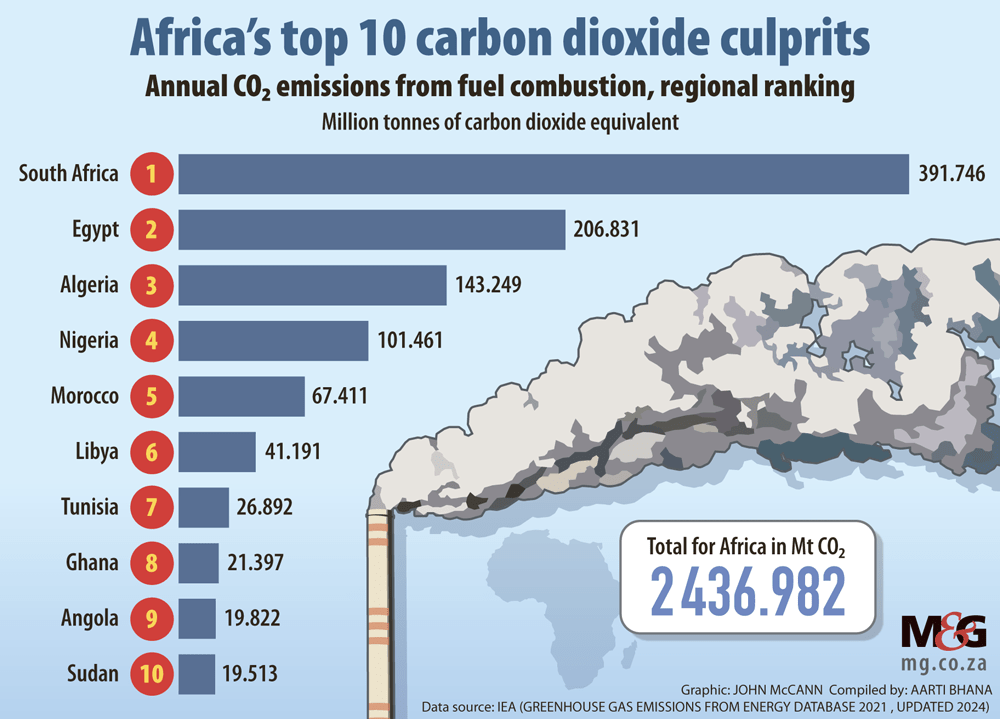

According to the United States Agency for International Development, South Africa is one of the world’s top 15 greenhouse gas emitters because of its over-reliance on coal as an energy source.

The new law makes provision for local departments and municipalities to take action.

“The involvement of or at least the decentralised nature, to some extent, where working with municipalities on climate change, is a lesson that many African countries can also learn,” Omari-Motsumi said.

South Africa is also playing a proactive role in leading negotiations on climate policies, and is using its position to lead conversations for the continent which is set to suffer considerably more than the rest of the world from the climate crisis, she added.

“South Africa makes a huge effort with regard to ensuring that, as Africa, we have one voice,” she said. “Even if you look at access to climate finance, they [South Africa] were one of the first countries as well to get accredited to the Green Climate Fund and access funding.”

Mohamed Adow, the director of climate change think-tank Power Shift Africa, said South Africa’s ability to recover from severe floods in KwaZulu-Natal was an indication of its adaptive capacity.

“In terms of climate impact, if you remember the flooding in Durban last year, [South Africa] is as affected as any other African country. The only difference is it may have greater adaptive capacity that helps it to actually recover much faster than the majority of sub-Saharan African countries,” he said.

But ultimately, he added, countries on the continent were suffering a similar fate at different degrees because of the failure of rich Western nations to take responsibility for the effect of their actions on climate.

“The climate problem has been principally caused by a wealthy minority who have also developed, in part by the rest of the world subsidising their development, because they polluted without facing the cost of doing so,” Adow said.

South Africa was ranked 92 out of 181 countries in a 2020 University of Notre Dame index looking at countries’ climate vulnerabilities and ability to adapt, according to the World Bank report.

“South Africa is highly vulnerable to climate variability and change due to the country’s high dependence on rain-fed agriculture and natural resources, high levels of poverty, particularly in rural areas, and a low adaptive capacity,” the report said.

In other African countries such as Malawi, Zimbabwe, Botswana and Zambia, droughts have destroyed crops and undermined food security.

Adow said: “Whether it’s drought, whether it’s flood, whether it’s locust invasion; some of the impacts that our communities are facing are the same across the continent, and South Africa, like any other African country, is on the front end of the climate threat.”

Omari-Motsumi said Africa’s agenda for 2024 United Nations climate change conference (COP29), set for November, would be to ensure that it gets more financing for adaptation.

“We are really pushing, as Africa, the adaptation agenda to ensure that we get more financing for adaptation, and secondly, we need adaptation to be considered as a global problem,” she said.

But Africa must also rely on its own resources to drive solutions for itself, Adow said, including tapping into the abundant renewable energy sources across the continent, using the arable land available to meet its food demand and boosting green industrialisation — including environment-friendly technology — to meet climate goals.

“So what we need is a pan-African industrial policy that allows us to aggregate the resources that are available in the continent and add value to those commodities in our continent to help meet Africa needs, and then sell the surplus,” he said.

The reporter’s attendance of the workshop in Kenya was sponsored by Power Shift Africa.