Christian Deschodt with his children Kara and Chris. (Photo supplied)

Field trips in search of dung beetles have taken Christian Deschodt, a doctoral student at the University of Pretoria, across Southern Africa in the past 20 years.

But it was on his regular walk on a familiar gravel farm road near his home that saw him stumble upon a new species.

“I am very fortunate,” he said. “I’ve got 20-odd years of experience so one then starts to learn where to look and what to look for. I just walked, saw the beetle, picked it up, held it in my fingers very carefully until I got home, and got it under the microscope. It was really cool and unexpected.”

This was just one of two new species that was recently described by Deschodt, who has been involved in the discovery and description of more than 50 dung beetle species.

News about the species, named Hathoronthophagus spinosa, spotted on his stroll was announced in Zootaxa, a scientific journal that specialises in updates about the discovery of new species.

Onthophagus pragtig. (Photo supplied)

Onthophagus pragtig. (Photo supplied)

Deschodt, together with his PhD supervisor, Catherine Sole of the department of zoology and entomology, also placed the species in a new genus, Hathoronthophagus.

Deschodt lives near Hartbeespoort Dam about 30km from the university’s Hatfield campus. After a morning of research work, he likes to stretch his legs by taking a walk to fetch his children from primary school.

In January last year, he set off to fetch his children. It had rained the previous day.

About 500m into the walk, he spotted a tiny chocolate brown dung beetle less than 5mm in size amid a hoard of common pugnacious ants.

After a quick look at it under the microscope, Deschodt realised it was the female of a species that he had never seen before. He named it after Hathor, an ancient Egyptian deity associated with joy, love, women, fertility and maternal care.

“She was often portrayed as a woman wearing a headdress of cow horns,” Deschodt said, “which reminded me of the longish horns of Hathoronthophagus spinosa.”

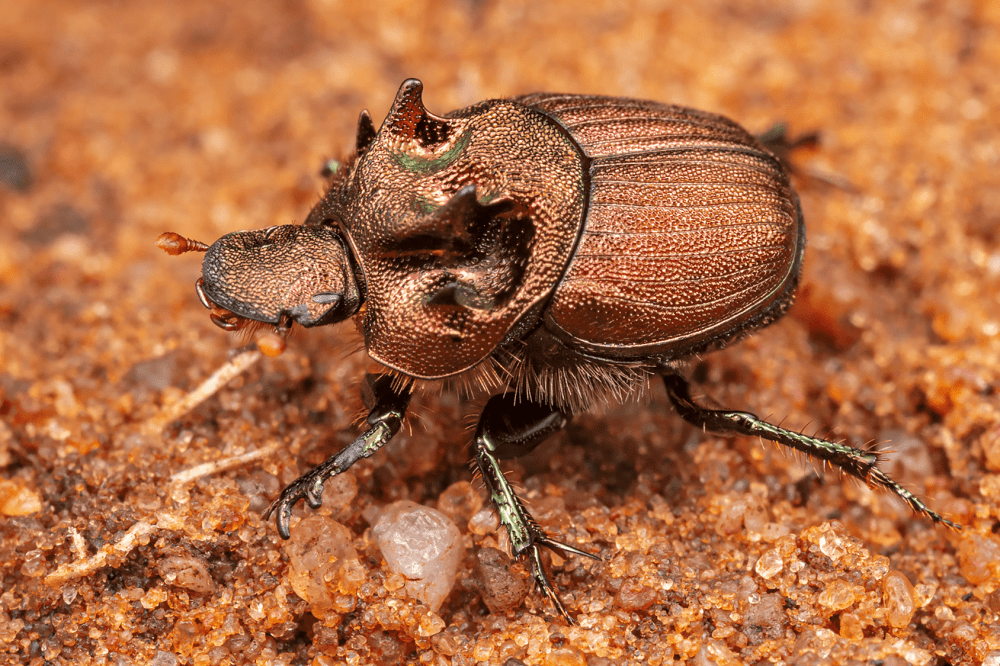

Hathoronthophagus spinosa

Hathoronthophagus spinosa

Despite having put out lures baited with cattle dung and extensively examining ant nests around Hartbeespoort, Deschodt has since had no luck in tracking down more specimens. He believes this particular species of dung beetle may live in ant nests, and may be providing a mutually beneficial service to its fellow insects.

“The nest might have been flooded — who knows what happened — it was out with the ants and there it was. The biology of those things are, at best, unknown.”

Other dung beetles that have antennas with eight segments, like Hathoronthophagus spinosa, have such a relationship with ants. Deschodt says more work will have to be done to confirm this hypothesis.

“I hope that news about this find will prompt other experts working in Southern Africa to explore the relatively unknown relationship between ants and dung beetles more intensively,” he said.

South Africa has roughly 500 species of dung beetle and there are more than 700 in Southern Africa. This diversity is partly a result of the varied geography and range of vegetation types, from fynbos and succulents to thickets and savannas.

Many species of dung beetles are specific about the type of dung they use. For instance, some only use elephant or rhino dung.

For his PhD, Deschodt is working on a flightless genus found in the arid parts of Namibia and western South Africa that only works with the dung pellets of the rock hyrax (dassie).

It is also a fallacy that dung beetles only feed on dung. Some species scavenge on dead frogs and chicken livers, or feed on different types of mushrooms.

In his latest paper, which also appeared in Zootaxa, Deschodt described yet another new species. Onthophagus pragtig probably only feeds on the innards of dead millipedes. It is one of 20 species that is part of a small group of dung beetles in the genus Onthophagus.

All other species in this group are known to prefer the soft internal organs (or viscera) of millipedes.

“These beetles are small and about the width of a millipede in cross-section,” Deschodt said.

“One after the other, they enter a millipede’s carcass via any breach in the body they can find. I’ve seen some sitting tightly packed together in a carcass, almost like a string of dark pearls. They scrape soft edible tissue off, then form these into small balls to feed on later. Onthophagus pragtig will form a ball with the viscera of a dead millipede and bury it directly under the millipede carcass.

“For dung beetles forming a ball to provision their offspring from something other than dung is already unique, but forming it from the innards of a millipede is quite extraordinary.”

Millipedes have hydrogen cyanide, hydrochloric acid, hydroquinones, benzoquinones, alkaloids and phenols inside them.

The species’ colour ranges from black, brown and orange to shiny coppery shades. Some can be metallic blue, green and red, while a few have coloured spots or markings. The coppery red metallic sheen of Onthophagus pragtig “makes it particularly beautiful, and almost jewel-like”.

“The epithet ‘pragtig’ is Afrikaans for ‘splendid’. It links this species with some other very closely related species within the same group, namely Onthophagus splendidus and Onthophagus splendidoides. All of them seem to prefer sandy soils.”

Christian Deschot. (Photo supplied)

Christian Deschot. (Photo supplied)

Examples of Onthophagus pragtig have been collected in Limpopo and the Northern Cape, and were described from specimens that are part of collections held at the university and the Ditsong Museum of Natural History in Pretoria.

The first known specimens of Onthophagus pragtig were collected by Deschodt’s mentor, Clarke Scholtz, who, before his retirement, was associated with the university’s department of zoology and entomology for many years. In the early 2000s, Deschodt was part of Scholtz’ research team that investigated the effect of livestock dips on dung beetle diversity.

He said it was difficult to study species like Onthophagus pragtig that do not have a specific relationship to dung, because they are not attracted to faeces bait.

Deschodt stressed the importance of dung beetle conservation. “If there were no dung beetles on Earth, we would be knee deep in shit within one year. This is literally what’s going to happen if we ignore dung beetles. We really have to look after them.

“We just have to start looking at these things and figuring out what’s going on. There are so many intricate webs between these animals and we are disturbing all these webs and one of these days we are going to disturb or break an important link and then there will be chaos.”

The idea behind all the dung beetle work is to get the message out that people start developing an interest in dung beetles. “Everybody thinks dung beetles just eat poop. There’s much more to them than just poop.”

Deschodt may be on the cusp of yet another discovery. “Yesterday it was a rainy day and I was driving the kids to school. I opened the gate and when I got out, I saw another beetle that might be undescribed. I don’t know what it is and we’ll see if it is new or not.”