Success demands effort, but specifically effort expended on the right ventures for the right reasons — this is worth remembering when times are hard, such as when I blew the whistle on my employer for withholding information relevant to the state capture enquiry

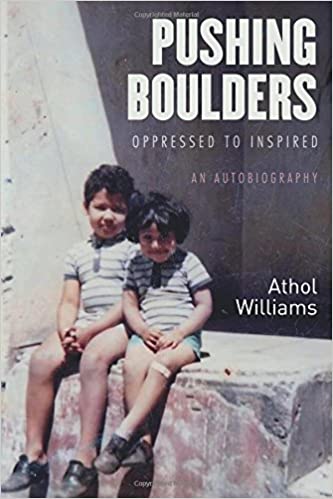

In my 2016 autobiography, Pushing Boulders, about growing up during apartheid, I invoked the image of the mythical character, Sisyphus, labouring to push a boulder up a hill.

For many, Sisyphus epitomises resilience, the ability to keep going despite the obstacles. We all know them, those people with “never-say-die” attitudes, who keep going no matter the odds and no matter what setbacks they face. We admire people who keep going and, better still, we admire those who succeed after relentless perseverance.

But we don’t all seem to have this resilience or not all of the time. Many of us are quick to give up when the going gets tough – we abandon projects, we quit our studies or walk away from relationships, often giving up on a dream. The civil society organisation Inyathelo reported in 2015 that for every three people who enrolled at a South African university, two would drop out. It is reported elsewhere that 80% of New Year’s resolutions fail. If you have been struggling to keep going or have already quit something important, it is clear that you are not alone. We wish we had the resilience of Sisyphus or those we admire, to keep going, to get up after falling, dust ourselves off and to keep going, but we don’t seem to be able to muster the strength to keep going.

In her book Grit, American psychologist Angela Duckworth challenges the common idea that intelligence and talent are the main drivers of success. She does not claim that talent plays no role in what we achieve, rather, what her research shows is that effort plays a greater role. “Effort builds skill,” Duckworth writes, “At the very same time, effort makes skill productive.”

What she is saying is that when we observe someone persisting with their endeavour and succeeding, we are seeing the result of effort to develop the skill required, plus we are observing the effort expended to deploy this developed skill successfully. “Effort counts twice,” she writes.

This indicates that we could attribute our shortcomings simply to lack of effort, that we simply need to push harder. That we need to develop that dogged determination — what Duckworth calls grit — to carry on despite failure and setbacks.

There seems to be nothing new or interesting in saying that to achieve anything we need to just keep going. Besides, with most good advice there is often counter-advice. We’re encouraged not to throw good money after bad, in other words, sometimes quitting is the right thing to do. Perhaps the project that you started was a distraction from something more important. Perhaps you were in the wrong degree programme or at the wrong university and so should quit to redirect your efforts. Perhaps that relationship was never going to work because it was a mismatch from the start.

The reality is that some relationships just have to end, some jobs should be quit, and some ventures are ill-advised. Some of us are never going to be great dancers or play the guitar or learn to code, no matter how hard we try. We have to wake up to this reality, if it is true, and move on. Sometimes we have to abandon one path of possibility to start journeying on another, and so quitting or our seeming lack of resilience, is a positive outcome because it opens us to new possibilities.

It seems the key to resilience then, and success as a result, is knowing that you’re doing the right thing, or that you’re on the right path and for the right reasons. This idea is captured profoundly by holocaust survivor Viktor Frankl in his book Man’s Search for Meaning, where he writes: “Those who have a ‘why’ to live, can bear with almost any ‘how’.” Once we have the ‘why’ or the reason for why we are pursuing a project or some path in life, we are better able to deal with the obstacles, failures and setbacks, and are better able to expend the effort, to push the boulder – the ‘how’ – to keep going and succeed.

Blowing the whistle

I experienced this quite acutely recently. It has been widely reported that in 2019 I blew the whistle on my employer, the US consultancy Bain, because I believed they were withholding information that would contribute to the country’s understanding of those involved in state capture and what they were planning.

Since then I have faced enormous battles. My physical and mental health has deteriorated because I was thrust into a legal hurricane where some parties were demanding information from me and others demanding my silence, all the while not knowing what my legal obligations were and what legal risks I was exposing myself to.

I feared for my safety as it became clear that there were many powerful people determined to ensure that I remain silent — not only my former employer but those with whom they had collaborated. I’ve had to go without an income for over a year and even now still face an uncertain future. I’ve had legal challenges to my affidavit and had the date of my testimony to the Zondo Commission moved twice.

I constantly have to deal with questions from colleagues, family, friends and the media over my actions, my intentions and what I hope to achieve. There are many days when it is simply too overwhelming, when I struggle to get my days going, or when I just sit at home dysfunctional. There are times when I have been tempted to simply take the financial settlement and agree to keep quiet. But I resist this temptation and muster the forces within me to keep going.

Increasingly I am asked: “How do you keep going?” My only answer is that I know I am doing the right thing for now and for the right reason. This is what I should be doing right now. Corruption and state capture is crippling our country and must be stopped. I feel that I can contribute to ridding our country of this injustice. I choose to follow an ethical path and so feel compelled to persist despite the high personal cost. I have the “why” as Frankl wrote, so I can deal with any “how”.

I believe knowing you’re on the right path and being there for the right reason goes a long way to enabling resilience. We are able to keep making the effort, to keep getting up when we fall, to keep pushing the boulder when it rolls back, because we have conviction to keep going.

When the going gets tough, I suggest you ask: “Why am I doing this?” If the answer satisfies you then keep going. If you have no good answer, then perhaps you should consider redirecting your efforts. Your answer could be that you’re doing this because you love doing it — a runner might answer in this way when encountering cramps during a race and keeps going for the love of running. Or the runner might say they will keep going because finishing the race has great meaning for them, or that finishing the race opens an opportunity to enter another race.

It is the reason for facing the challenges, the meaning behind the endeavour, that keeps them going, that keeps me going and will keep you going. Success requires effort, no doubt, but success requires that this effort be expended on the right ventures for the right reasons — this ultimately keeps us going until we achieve success.

And so, despite all my challenges as a whistleblower, I continue. I will not give up because I know why I am doing this. I continue to urge my former employer to do the right thing through the media, social media and an online campaign, and I continue to espouse the need for us to exercise moral courage to do the right thing in our country. I try to live with an attitude of possibility, and this helps my resilience.

Right now, early in 2021, when things look bleak, we may already be tempted to throw in the towel on some of our plans and even a dream. But now is exactly the time that we need resilience. It is the dogged effort — the grit — that we put in that will get us to the finish line.

As I wrote in my book, “Life is not about the boulders. Life is about the dream that lay on the other side of the boulders.”

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.