World view: German Chancellor Olaf Scholz (right) stands with Ajay Banga, President of the World Bank (left), on a balcony of the town hall before a session of the Hamburg Sustainability Conference on 7 October in Hamburg, Germany. Photo: Marcus Brandt/Getty Images

The world as we know it — divided, unequal and unfair — is not sustainable. Global institutions have failed far too many people and must be reformed.

It will no longer benefit the wealthy to hoard their riches in isolation. These were some of the messages delivered at the inaugural Hamburg Sustainability Conference that took place in Germany this week.

Organised by the German federal ministry for economic cooperation and development, the United Nations Development Programme, the Michael Otto Foundation for Sustainability and the city itself, its intention was to foster better multilateral relations between states and global commerce.

The promise was that the world, and the way we live, could take meaningful steps to becoming sustainable — that most amorphous of humanity’s targets. The risk was that it would be another talk shop; a spiritual cousin of the World Economic Forum which, in pragmatic circles, is respected as little more than a glorified networking session.

There was indeed plenty of networking over coffee and brezeln; euphemistic assurances of strengthening ties and taking the dialogue forward and sporadic assaults of acronyms and platitudes. But there were also firm admissions and uncomfortable questions.

One constant reminder was that neither Europe, nor anywhere else, is inoculated against the troubles of the rest of the world.

During the opening session, in the capacious, ornate Hamburg City Hall, Barbados President Mia Mottley drove the point home: “If we continue to have countries being marginalised, you then have increased migration, which then causes the problems you’re seeing in Europe.

“And then geopolitics becomes a toxic conversation.”

She added it was imperative that the world embraced the spirit of ubuntu and elevated its empathy for those on the opposite end of a border.

At a later session, World Bank president Ajay Banga continued the narrative, drawing on recent data from the bank that predicted 1.2 billion people will come of working age in the Global South over the next 10 years, but only 400 million jobs will be created.

“We talk about it as if it is a dividend,” he said. “It is a dividend, yes, if those people get clean air, clean water and a chance to get a job.

“If they don’t get a job, it’s not a demographic dividend. It is a very big challenge for these people.

“And it’s not just them; it will come to all our shores. Because those people will be forced to migrate. So this is not a problem you can put behind a wall and hope that it becomes his problem. It’s not going to be. It’s going to be our problem together.”

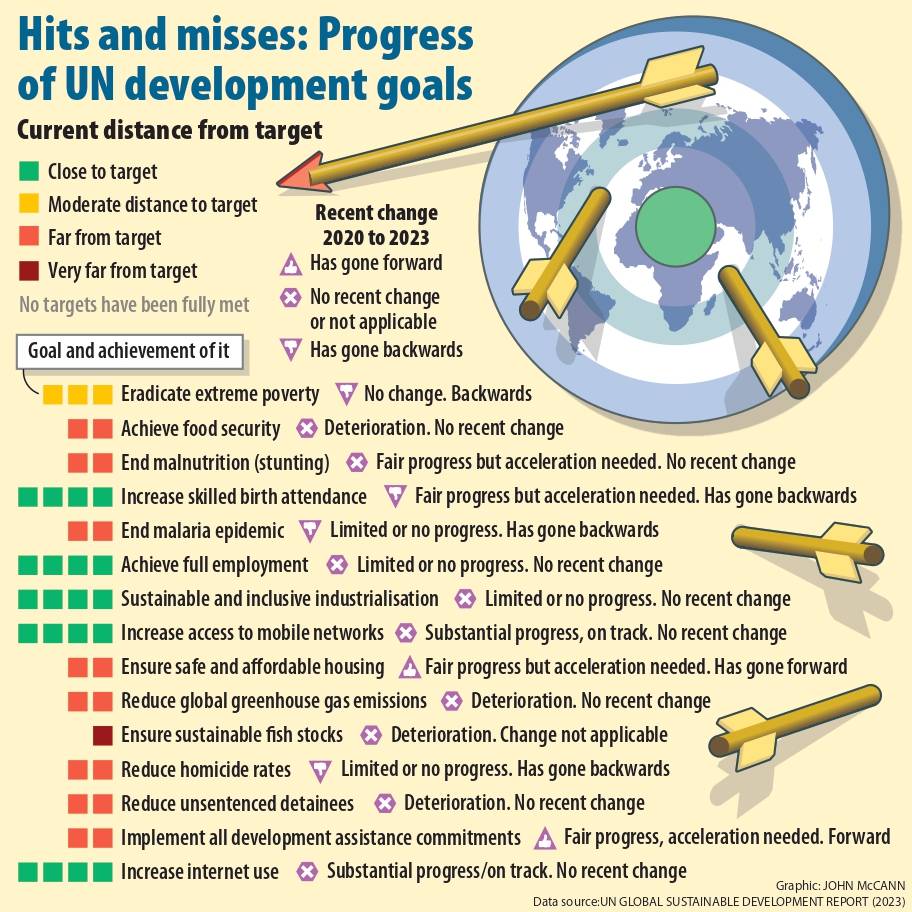

The world’s wayward march towards the sustainable development goals was a recurring theme during the two days of the conference.

Adopted by all UN member states in 2015, the 17 goals are the conscience of globalised society. Their intention was to secure dignity, co-operation and sustainability across the globe by 2030.

Almost all of them are on a trajectory of failure.

That reality formed the premise of an unanimous admission that the international order and its ways of doing things are not optimal.

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

(Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

At one point, journalist and president of the School of Oriental and African Studies in the United Kingdom Zeinab Badawi challenged International Monetary Fund (IMF) head Kristalina Georgieva on how she was going to remedy the deep distrust much of the developing world has for her institution. While she arguably prevaricated, she did later talk up the need to improve multilateral communication.

“There is something that is very important for this discussion. And it is all of us working together. When we at the IMF look at the policy environment in a country … What can we do about subsidies, how can we improve the performance of the public sector? How can we bring more private investors?

“We do that hand in hand with the World Bank. This is something that has always been on paper, true, but saying it now in this room we need to make it a reality,” Georgieva said.

The sentiment in Hamburg can be linked to that which we’ve seen play out on the world stage of late.

Last month in New York, the UN adopted a “pact for the future”. Secretary general António Guterres described it as a “step-change towards more effective, inclusive, networked multilateralism”. In his own UN speech, President Cyril Ramaphosa said next year’s G20 must discuss how that new dispensation will benefit the Global South.

The choice of host city is also symbolic. The Free and Hanseatic City of Hamburg, as it is officially known, earned its prosperity through centuries of operating as a key trading port in the North Sea; specifically one that offered tax-free trade zones.

The baroque buildings preserved throughout its centre represent the wealth that can be generated in the laissez-faire market.

It is also a worthy poster child of the green transition. With subways and bus routes around every major block, public transport is the best way to get around. Bicycle paths are prioritised on every main road — accidentally jaywalking into one sets up an angry rollicking from an onrushing rider.

Charging ports are common for electric vehicles, which are prolific.

But Hamburg is also the world that has left developing nations behind.

Even by German standards, the city is incredibly wealthy. And visibly so. Unlike nearby Berlin, which is more cosmopolitan and artsy, Hamburg is almost disturbingly pristine. Rarely will you see a car on the road that is even close to a decade old. Everyone is dressed immaculately (and, to a degree, uniformly).

The sight of an army of white yacht sails heading into the sunset on the Elbe, as beautiful as it might be, is a reminder that life here is different to that in most of the rest of the world.

On the way to day two of the event, a young woman earnestly said the programme had changed and produced a new schedule. Of particular interest were the panels “Using debt to secure resources and extract wealth from the Global South” and “Securing and militarising strategic trade routes to control supply chains and exploit critical resources”.

Both were to take place in room Status Quo Group I. Only after reading that lunch would be served “with a side of greenwashing” did the penny eventually drop.

This creative form of protest articulates a frustration that will always accompany occasions like this. The very people waxing lyrical about the world’s problems often represent the power structures that helped cause them.

World elites, similarly, are regularly criticised for trading in talking points and ignoring the minutia that are key to understanding development problems.

“How the heck can we talk about digitising Africa when people don’t have electricity?” Banga asked.

“What are they going to do, charge their cellphone by attaching it to the sun? We need to get them the basic right of power. Without power, nothing is going to happen.”

That necessity might well bring it into conflict with the West’s green transition ambitions.

Mottley said: “You say to small states, ‘You need to play your part, because all of us need to go in the direction of renewable energy. It’s good for jobs, it’s good for investment.’ What we forget is that small states don’t have the economies of scale. And therefore the costs of renewable energy may well be more expensive than traditional fossil fuels. So how do we balance out the differential?”

That differential, many argued throughout the conference, should be balanced by the introduction of new global norms that have the effect of redistributing superabundance to developmental needs. These would include levies on business and luxury travel; a rethinking of currency exchange models and general wealth taxes implemented on an international scale.

“Capital is a coward,” Badawi had remarked earlier. Institutions such as the World Bank would have to offer greater insurance and risk-mitigating procedures to encourage investors to take a stake in the Global South.

As intriguing as some of the proposals were, whether they arrive at the urgency with which the world needs them is another matter.

As Mottley quipped: “Tortoises move in the right direction too.”

The writer’s travel expenses were covered by the Hamburg Sustainability Conference.