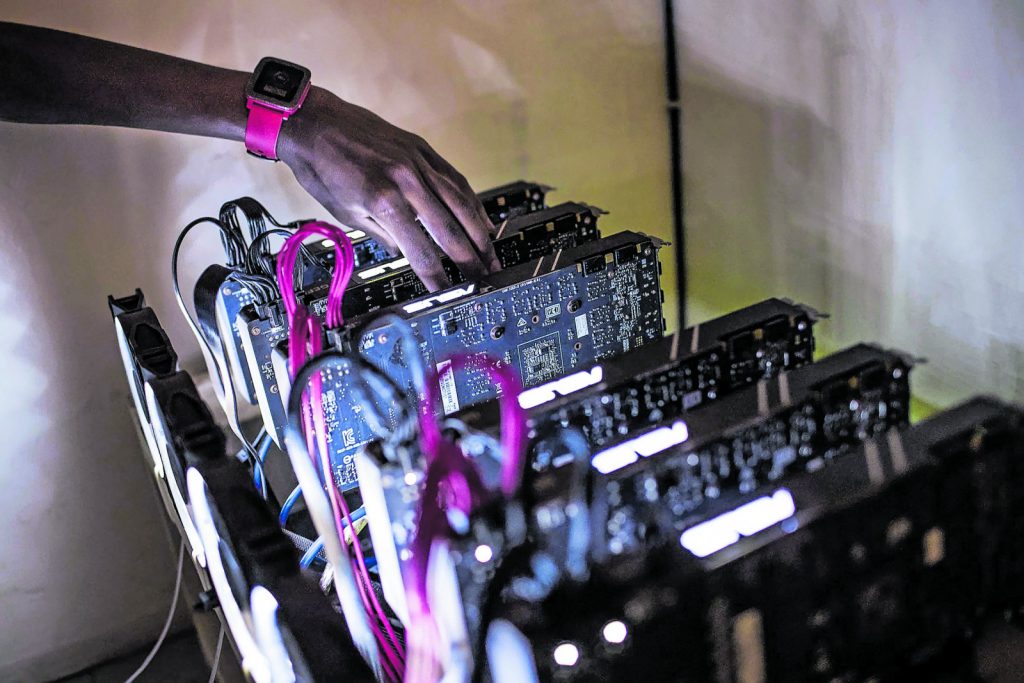

From hero to villain: Sam Bankman-Fried (above), founder and chief executive of the FTX crypto exchange. Computers (below) used for bitcoin ‘mining’ at the the home of bitcoin ‘miner’ Eugen Mutai in Nairobi, Kenya.

The founder of the crypto Dogecoin, Jackson Palmer, was quoted earlier this year saying he wished crypto “would implode a bit more quickly and people would learn their lesson”. This past week, the crypto exchange, FTX, imploded, but time will tell whether people will have learnt their lesson.

FTX was one of the biggest crypto-currency exchanges in the world. Launched in 2019 by MIT graduate Sam Bankman-Fried, the exchange quickly grew to become one of the most popular trading platforms. At his peak, 30-year-old Bankman-Fried was worth $26 billion. All this changed in a matter of a few hours; the crypto hero and chief executive of the then second-largest crypto exchange turned into the ultimate crypto villain.

First, some context. FTX was a centralised exchange designed to be a more user-friendly and efficient alternative to existing centralised exchanges, offering a wider array of financial products such as derivatives, leveraged tokens and options.

But FTX faced a number of problems since its launch. In June 2019, the platform was hacked and more than $6 million of cryptocurrency was stolen. In December 2019, FTX suffered another major setback when it was forced to delist several popular altcoins because of United States regulatory pressure.

Despite these setbacks, FTX remained one of the leading crypto-currency exchanges in terms of trading volume and liquidity.

FTX was registered in the Bahamas and regulated by the Securities Commission of the Bahamas. Technically speaking, FTX did not offer its services to US residents.

On 9 November this year, crypto media service CoinDesk published an article about the rumoured state of the FTX balance sheet, and the deep linkages between FTX and the sister company, Alamenda Research.

Bloomberg’s Matt Levine described the mess so very well: “If a troubled company has a few days to beg potential investors for a bailout before it files for bankruptcy, and it sends those investors its balance sheet so they can consider investing, and they all pass, and then the company files for bankruptcy, of course the balance sheet was bad. That is not a state of affairs that is consistent with a pristine fortress balance sheet.

“But there is a range of possible badness, even in bankruptcy, and the balance sheet that Sam Bankman-Fried’s failed crypto exchange FTX.com sent to potential investors last week before filing for bankruptcy on Friday is very bad. It’s an Excel file full of the howling of ghosts and the shrieking of tortured souls.

“If you look too long at that spreadsheet, you will go insane.”

The balance sheet was “very bad” because it showed that FTX had created its own cryptocurrencies (FTT and Serum), which it then used as “assets” on its balance sheet. Simplistically, FTX received $16 billion in customer cash (liabilities) but the asset side reflects the self-created cryptocurrency.

So, although customers gave FTX $16 billion, $9 billion of real assets were missing from the balance sheet. Where was the cash or less risky assets that coincide with the value of the money received from customers?

When the chief executive of rival crypto exchange, Binance, tweeted that his company was selling half a billion dollars worth of FTT, the market followed suit and carnage ensued.

Things did not get any better when FTX’s major investor, Sequoia Capital, informed investors that the FTX problem wasn’t a liquidity crisis but a solvency crisis. Consequently, by the end of the week, FTX’s value had plummeted from a peak of $32 billion to exactly one dollar.

Even in an environment of people acting in good faith, crypto is a complicated solution to financial inclusion. First, its proponents argue that these new technologies have the potential to provide users with access to financial services that they otherwise would not have. For example, cryptocurrency wallets can be used to store and send money, receive payments, or make purchases online without the need for a bank account.

This is important for people living in volatile markets with weak and depreciating currencies, and limited options for storing and growing value.

In addition, blockchain technology can be used to create decentralised applications that provide financial services directly to users without the need for intermediaries such as banks or mobile money providers. At least that is the argument.

Aside from the issues of volatility, which make it difficult for people to transact day to day, crypto enthusiasts often underplay the very real risks that vulnerable users face when they trade speculative assets.

Payments into these exchanges are not deposits and are therefore not protected in the same way as deposits made to financial institutions such as banks. It is like gambling; when you lose your money at a casino, you can’t get that money back. Losers cannot retrospectively demand that regulators treat their lost monies as deposits.

Crypto messaging often emphasises decentralisation and the removal of regulators from personal finance. This is great when the values of these assets are going up, but the absence of regulators is acutely felt when these assets crash.

What happened with FTX is, of course, illegal. Exchanges are not allowed to use the money received from customers for investments unrelated to the core function of the exchange. What happened with FTX is a crime for which Bankman-Fried has been detained by officials in the Bahamas, but outsized losses in crypto are a major risk even in the absence of criminality.

The much-hyped promise of crypto-currency and blockchain technology to provide financial inclusion for the world’s unbanked and underbanked population has yet to materialise. So far, crypto assets have largely benefited those who are already financially well-off, leaving behind the most vulnerable people in society.

This is because the cryptocurrency industry is still largely unregulated, which has resulted in a number of scams and frauds that have targeted unsophisticated investors. In addition, the volatile nature of crypto assets means that even if someone does manage to make money from them, they are just as likely to lose it all overnight.

Does that mean there is no role for blockchain technology? Absolutely not.

But it is important to differentiate between the regulation of technology and the regulation of finance.

One of the ways in which crypto-bros have hidden the real risks of crypto trading from vulnerable users is by using tech lingo to hide the simple economics of the transaction — that tokens are created out of lines of code, given a value that is not based on any real economic value, and traded.

In time we will probably find the utility in blockchain technologies in simplifying the delivery of financial services. In the meantime, regulators need to do a lot more than define crypto to protect vulnerable individuals. That’s what financial inclusion is about.

The mistake many regulators make is to look at people like Bankman-Fried and think it is only middle-class white guys who trade in crypto. It’s not. Blockchainalysis says that between 2020 and 2021, the cryptocurrency industry in Africa grew by 1 200% with Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Tanzania among the 20 countries that use cryptocurrencies the most.

Hundreds of these tokens are created in the Global North, available to millions of vulnerable people around the world, including Africa. They symbolise a global transfer of value from the South to the North, creating mega billionaires such as Bankman-Fried.

Without better clarity from regulators and a stronger hand in ensuring that traded tokens are at least being sold by players with strong boards, with strong risk and compliance departments, these tokens will keep crashing and millions of vulnerable people will keep losing their money.

Going back to the Jackson Palmer quote, we can only hope that regulators at least learn from these great crashes, because, contrary to what many may believe in the tech industry, regulation can be a powerful contributor towards useful and meaningful innovation.

Zama Ndlovu is a columnist, communicator and the author of A Bad Black’s Manifesto.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.