The pace and pattern of African industrial development have remained a concern among development scholars and policymakers

The African Continental Free Trade Agreement (AfCFTA) is one of the flagship projects of Agenda 2063, which aims to integrate and transform the continent into the largest single market for goods and services with an estimated worth of $3.4 trillion in GDP and 1.3 billion in population.

Against Africa’s low levels of industrialisation and other structural economic challenges, it remains an open question whether the AfCFTA can deliver on its promise of creating a prosperous free trade area.

The principal objectives of the AfCFTA agreement include: (i) gradually removing trade tariffs; (ii) gradually removing non-tariff barriers; (iii) harmonising customs, trade facilitation, and border transit procedures; (iv) promoting cooperation on technical barriers to trade (TBTs) and sanitary and phytosanitary (SPS) measures; (v) developing and promoting regional and continental value chains; and (vi) promoting socioeconomic development, diversification, and industrialisation across Africa.

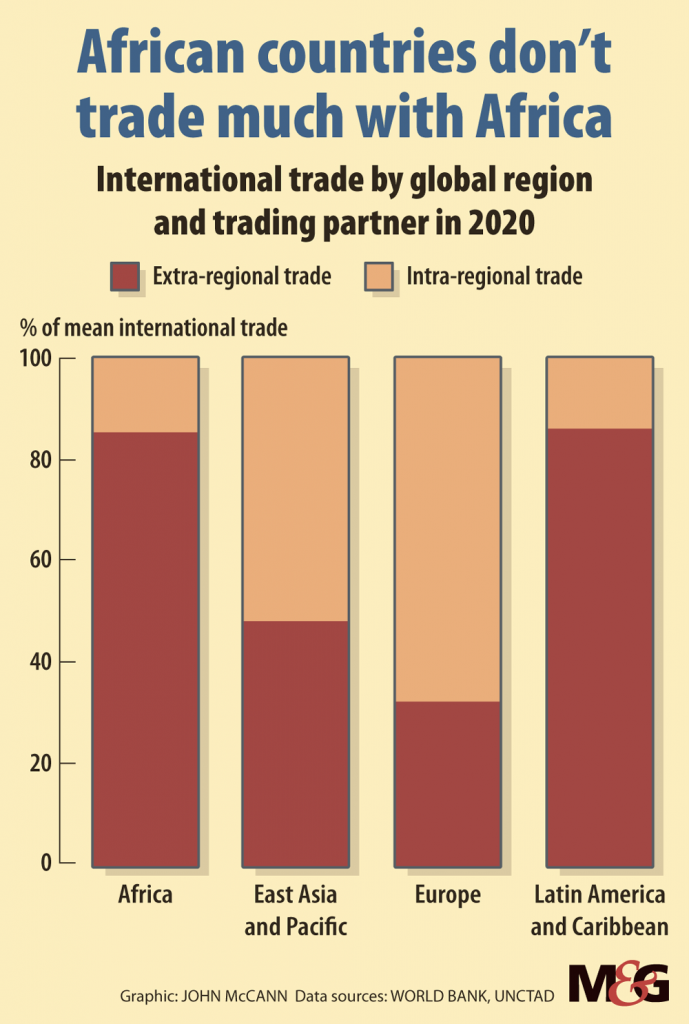

The 2020 World Bank trade statistics show intra-African regional trade to be among the lowest in the world at 15%, compared to 68% in Europe and 52% in East Asia and the Pacific.

Although minimal, intra-African trade mostly comprises processed goods and services, with commodity goods usually traded outside the region with little or no beneficiation.

The pace and pattern of African industrial development have remained a concern among development scholars and policymakers. Structural change on the African continent has been unusually slow, differing from the pattern observed in other parts of the world, where structural change is associated with rapid industrialisation.

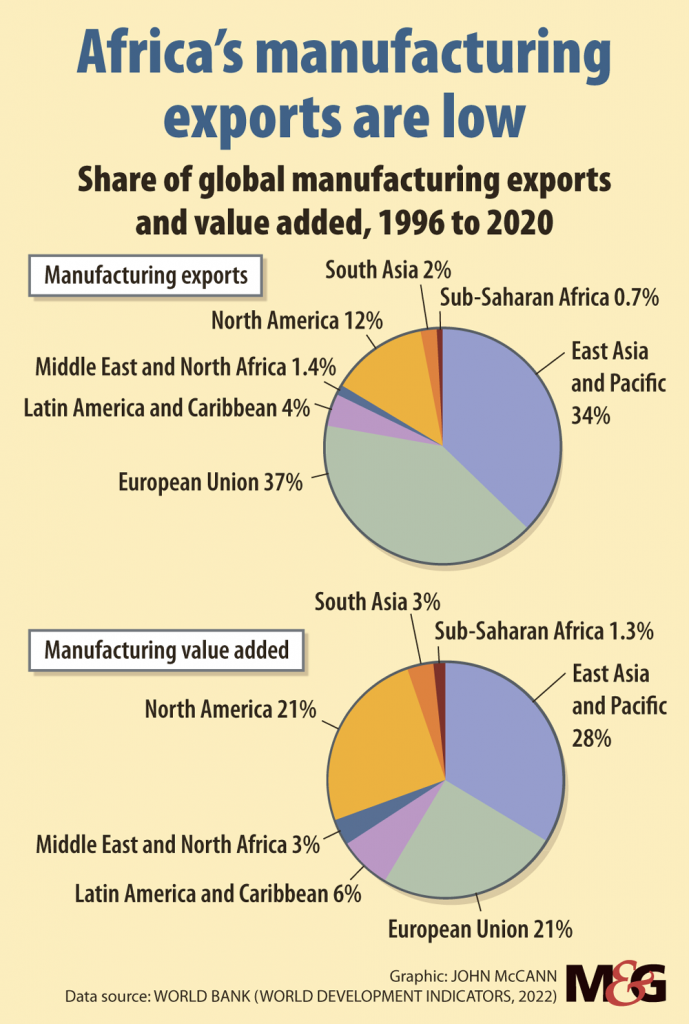

The graphic above depicts the global distribution of manufacturing exports and value-added from 1996 to 2020. Sub-Saharan Africa’s contribution to global manufacturing remains the lowest in the world, averaging less than 1% in exports and over 1% in value added.

Similarly, the Middle East and North Africa’s contribution to global manufacturing exports and value-added shows 1.4 and 3%, respectively. In contrast to East Asia and Pacific, 34% in global manufacturing exports and 28% in global manufacturing value-added.

Against the backdrop of questioning whether the AfCFTA can deliver on its promise of creating a prosperous free trade area, are three arguments that favour the proposition that industrialisation is a precondition for an effective free trade area in Africa.

Trade specialisation

One aim of the AfCFTA is to boost intra-regional trade. But the low levels of intra-African trade reflect the corresponding low levels of manufacturing export specialisation. In that case, industrialisation is a precondition for the success of the AfCFTA. There is a strong global correlation between manufacturing export specialisation and intra-regional trade. Africa and South Asian regions exhibit the lowest global manufacturing export shares and the lowest shares of intra-regional trade. Most African economies specialised in commodity exports.

In some African economies, commodity exports are as high as 90% of total merchandise exports. Given that small manufacturing and industrial production is taking place on the continent, it is only logical that intra-African trade would remain small while exhibiting a larger share of extra-regional trade.

Global value chain participation

The AfCFTA also aims to stimulate the development of regional value chains as a precursor to global value chain (GVC) participation. But the feasibility of this objective remains to be determined, considering the current state of Africa’s industrial development. Global or regional value chain participation hinges on the fragmentation of production across different countries with different comparative advantages to achieve cost efficiency.

The data support the perspective that there must be some level of industrialisation before any value-adding GVC participation would occur. Therefore, African economies must prioritise developing their industrial capabilities and creating an industrial base to reap the maximum benefit of a regional free trade area through GVC participation.

Industrial policy

Although trade agreements are good at preventing mercantilist beggar-thy-neighbour and beggar-thyself policies that undermine the collective good of member countries. They could have self-limiting unintended consequences if sufficient safeguards are not built into the design and implementation.

For instance, free trade agreements can constrain low-income economies’ capacity to effectively manage their industrial policies to address pervasive market failures and other structural economic challenges. Given that in entering free trade agreements, countries cede some of their agency to coordinate industrial policy, it is incumbent on the African Union to coordinate a broad base continental industrial policy that will benefit all parties.

With technical support from the United Nations Industrial Development Organisation, the African Union should set up a regional industrial cooperation scheme as part of the industrial development arm of the AfCFTA economic cooperation, à la ASEAN Industrial Cooperation and other similar regional initiatives.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Mail & Guardian.