Top floor: Actresses Sasha Vinni and Leslie Glass with publisher Bob Guccione at a Penthouse event in New York in 1994. Photo: Steve Eichner/Getty Images

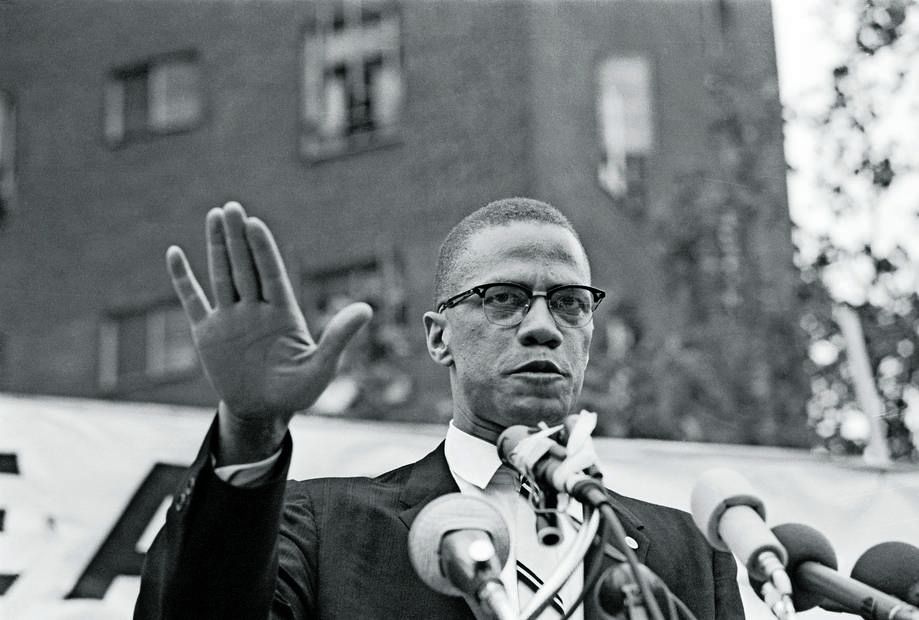

Malcolm X was taken aback by the immense crowds that greeted him when he first started lecturing on college campuses. The only explanation, he later concluded in his autobiography, was Playboy magazine.

He had sat for an interview in 1963, proudly holding the mantle of chief of staff of the emerging Nation of Islam. His incendiary responses were the hallmark of the combative persona that would characterise the next decade of his public life.

“The devil will never publish that,” he assured his interviewer.

But the devil did. In verbatim Q&A format, nestled amid an asphyxiating collection of alcohol and cigarette advertisements — about 50 pages before the “perky and petite” Playmate of the Year’s pictorial.

The dirty magazine hidden under countless dorm bunks had exposed American youth to one of the most radical thinkers of the 20th century. To civil rights discussion. Frat boys, white bumpkins and young miscreants who did not care for anything that did not come out of a beer keg.

Their generational successors will never share their experiences. Many have never flipped through a magazine — dirty or otherwise. And their lewd internet expeditions are in no danger of being hijacked by deliberations on Black Nationalism.

With print products massacred in the 21st century, no one has cared to mourn the demise of the adult magazine. And it’s not hard to understand why — the “gentlemen’s pages” embody conceptions of masculinity at their most archaic and pernicious.

But looking back today, in the age of the internet, in a time when most of us have forgotten the cultural cachet print products once held, it can be startling to relive the essays, stories, interviews, and even hard journalism, that appeared in pages primarily sought after for featuring women in various stages of undress.

Buying Playboy for the articles was a joke told ad nauseam. It was as misleading as it was unfunny … perhaps even for the raunchier competitors it helped spawn.

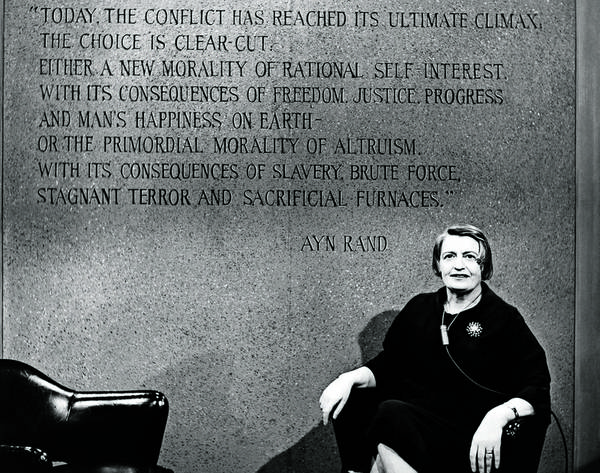

Centrebold: ‘Playboy’ publisher Hugh Hefner gave a voice to intellectuals of the times, including women, such as controversial writer Ayn Rand. (Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Centrebold: ‘Playboy’ publisher Hugh Hefner gave a voice to intellectuals of the times, including women, such as controversial writer Ayn Rand. (Archive Photos/Getty Images)

Raw introspection

Good writing was a key part of the strategy at Playboy, a magazine that shook the post-war residue off a genteel America crammed with frustrated husbands and agitated bachelors.

Founder Hugh Hefner famously wrote in the inaugural December 1953 edition that the modern man desired to invite women over for a fluent discussion on Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz and sex. The message was clear — the sexual revolution must be accompanied by taste and sophistication.

Yet those same opening pages that professed a love of art and philosophy featured nude images of an unwitting Marilyn Monroe. She had posed for the photos out of desperation to pay her rent prior to becoming famous — reportedly for $50 — and the shrewd Hefner scooped them up from a third party four years later.

The move catapulted the magazine into relevance but stuck on a badge of tackiness it could never shake off, no matter the intellectual dress it threw over the naked bodies.

Which didn’t stop it from trying.

You would struggle to name a notable author of the 20th century who was not published in its pages at some point. Vladimir Nabokov, Kurt Vonnegut, Nadine Gordimer, John Updike, John le Carré — to name a handful — appeared in the early days. Ray Bradbury’s Fahrenheit 451 was even serialised across three editions in 1954 — the same time that the book’s publisher was releasing expurgated editions behind the author’s back.

As eclectic as Playboy’s portfolio is, the Big Interview arguably carries the heaviest legacy.

It began as an afterthought. Little-known writer Alex Haley had given associate editor Murray Fisher a half-written Miles Davis interview he was struggling to drag towards coherence. Fisher was drawn in by the trumpeter’s searing racial criticisms and sent his man back to spend more time with his subject.

It was that assiduousness that elevated the Q&A beyond the superficial celebrity chinwag. As the LA Times wrote in his obituary in 2002, his standards called “for hundreds of questions and hours of talk, coupled with his admonition ‘but then you don’t leave’.”

In September 1962, the Big Interview was born.

“I ain’t no entertainer and ain’t trying to be one,” The “Prince of Darkness” declared definitely. Davis articulated the frustration of an artist continually chastised for focusing wholly on his craft who, thanks to his race, was expected to deliver droll histrionics along with his formidable trumpeting.

“My troubles started when I learned to play the trumpet and hadn’t learned to dance.”

It is hard to overstate just how far such ideas would have flown over the conventional media’s window of acceptability in the early 1960s. The interview also returned the voice to the subject, reclaiming it from staff writers and TV presenters who were often all too willing to masticate material into digestible segments.

Titans across politics, entertainment and the intelligentsia, from Bertrand Russell to Fidel Castro, would feature in the slot over the subsequent decades.

Haley persuaded Malcolm X to sit for multiple sessions in 1963. When “the devil” — the white man, not specifically Playboy — preserved his meaning, it set up the relationship to use the same author to pen his autobiography, one of the 20th century’s most indomitable pieces of non-fiction.

The cultured world of boxing was still reeling from the unthinkable dethroning of Sonny Liston when Muhammad Ali sat for an interview. He had just won the heavyweight championship, had changed his name less than 24 hours later and enraged a tradition-soaked sport with his brash poetry. His interview now reads as a historic prelude to pugilism’s most exciting epoch.

Martin Luther King appeared in the segment in January 1965, shortly after winning the Nobel Peace Prize. He spoke candidly about mistakes he made in the Montgomery bus boycott, and allegations of him being an “Uncle Tom”, and discussed at length his philosophy of militant nonviolence.

That a mainstream magazine would feature such words at the height of the civil rights movement was a great point of pride for Hefner.

But initially missing from the feature was an authoritative female voice. It arrived, via interviewer Alvin Toffler in the form of Ayn Rand — an iconoclast and all-around social troublemaker of the time.

“The real bird of paradise Toffler captured for Playboy in 1964 was Ayn Rand, the first female intellect given voice in the magazine,” Thomas Weyr wrote in the Reaching for Paradise: The Playboy Vision of America.

Ayn Rand was the first female given a voice in ‘Playboy’ (Photo by Raimondo Borea/Photo Researchers History/Getty Images)

Ayn Rand was the first female given a voice in ‘Playboy’ (Photo by Raimondo Borea/Photo Researchers History/Getty Images)

“Miss Rand did not disappoint. She dominated the interview with sharply phrased opinions that rode over Toffler’s questions like the charge of Czarist cavalry.”

The front-page hook of that April edition: “Ladies of the iron curtain”. The unintentional juxtaposition tells its own story.

Germaine Greer — a radical feminist feared by the male-dominated media — articulated fervent criticism of the very pages on which she featured. She lamented that women were reduced to a fetish by parading them as “pork chops”. Her argument drew a line between the puritanical and the hypocritical: “No, I’m not against nudity, and I will pay dues to Playboy when it runs a man in the gatefold. You can even keep the Playmate.”

Playboy might have prided itself on lending a loudspeaker to feminist thought but it would be a stretch to think the magazine was progressive in gender attitudes in all facets.

One of the uglier blemishes in the magazine’s writing catalogue came in 1968 when its editors suggested sci-fi savant Ursula le Guin should publish under her initials — concealing her gender — because a female author might make readers nervous.

Reflecting on the novelette Nine Lives, Le Guin later expressed regret that she had gone ahead with the idea.

“It was the first (and is the only) time I met with anything I understood as sexual prejudice, against me as a woman writer, from any editor or publisher; and it seemed so silly, so grotesque, that I failed to see that it was also important.”

Malcolm X. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Malcolm X. (Bettmann/Getty Images)

Ray Bradbury. (Sophie Bassouls/Getty Images)

Ray Bradbury. (Sophie Bassouls/Getty Images)

Miles Davis. (Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images)

Taste: In contrast to the hyperspecialised long tail of the internet, magazines provided curated experiences that could accommodate high- and lowbrow subjects between their covers. All three of these men appeared in ‘Playboy’

Miles Davis. (Jack Vartoogian/Getty Images)

Taste: In contrast to the hyperspecialised long tail of the internet, magazines provided curated experiences that could accommodate high- and lowbrow subjects between their covers. All three of these men appeared in ‘Playboy’

Pubic hair and propaganda

Bob Guccione, gold chains submerged in the chest hair visible between his open buttons, began snapping pictures of naked women in 1965. He had no formal photography training but called on his art background to airbrush the images in postproduction, giving them the soft-focus effect that would become the signature of his new empire. Penthouse arrived in the US in 1969, the first serious challenger to the bunnies’ turf.

Hefner declared that the “Pubic Wars” had begun. And, as when Hannibal’s elephants charged towards Rome, new weapons appeared on the battlefield. The unspoken law of the industry was that nudity could be sold as art — not pornography — as long as a strategic lampshade obstructed the woman’s lower half. But Penthouse unleashed the first wisps of pubic hair across a centrefold, setting the scene for a dare-to-show-more feud.

The challenge didn’t end with risqué poses. Guccione vowed to crush Playboy as a cultural and intellectual force as well. And, just as with its contemporary, there are any number of pieces to cherry-pick — pieces that were impactful and would by no means be anachronistic if published today. His stratagem, however, was to go beyond essays and stories … and actually commit bona fide acts of journalism.

Over the years, the Penthouse pages could boast recognised investigative journalists such as Craig Karpel, James Dale Davidson, Ernest Volkman and Pulitzer prize-winner Seymour Hersh. They brought in scoops and scandals, promising an upgrade to the highfalutin ruminations of its competitor.

Of course, there were plenty of those as well. Just as with its predecessor, the top writers and thinkers of the 20th century found their bylines printed in the magazine at some point.

This included original fiction from James Baldwin, Stephen King and Joyce Carol Oates and a missive from prolific science fiction author Isaac Asimov on the perils of teaching creationism in schools.

The fingernail-pulling frustration of researching Penthouse writing is that most of it does not exist digitally. Anything pre-21st century has simply not been uploaded. Your only options if you want to read most of the material today would be to find an archived PDF (rare), purchase a backdated issue from a sketchy site or shell out for a print copy on eBay.

It’s bemusing that the magazine didn’t make more of an attempt to leverage the archive throughout the years of plummeting sales — say, in the vein of The New York Times. Boasting a one-of-a-kind Baldwin story is surely a selling point. (Or perhaps we are grossly engorging the idea of buying the magazine for the articles.)

A new hustle

When Hustler was founded in 1974, any remaining pretensions of the erudite nudie mag were shredded. As was the unspoken rule of what was acceptable photography. Spread-legged women replaced the conspicuous lampshades. Graphic positions proliferated and the pictures ultimately became what we know porn to be today.

Founder Larry Flynt was also a different man to the thinking lotharios his rival publishers portrayed themselves as.

He wanted you to know that he was salt-of-the-Earth. A man with mud under his shoes who is more likely to be found sipping cheap beer at a crusty strip joint than partying with Hollywood A-listers. Indeed, he owned several — Hustler was originally designed as nothing more than a pamphlet to lure in customers.

If the content had anything in common with its predecessors, it was that Flynt believed there was more to the magazine game than convincing the fairer sex to part with their clothes. His specific schtick: free speech.

It’s debatable whether he had always been so strong in his values but, after would-be censors began clucking, Flynt fashioned himself as a liberal hero and guardian of free speech.

That self-styled legend grew further after a white supremacist shot him in 1978 for publishing images of a black man penetrating a white woman. The bullet struck his spinal cord and he became reliant on the wheelchair that would form the centrepiece of his public caricature from then on.

Self-refection: ‘Hustler’ publisher Larry Flynt built an image of himself as a liberal hero and defender of free speech. Photo: Steve Grayson/Getty Images

Self-refection: ‘Hustler’ publisher Larry Flynt built an image of himself as a liberal hero and defender of free speech. Photo: Steve Grayson/Getty Images

To Flynt, there was no corner that should remain dark and no secret that should stay untold, an ethos epitomised by taking the US Defence Department to court in 2002 after the Pentagon refused a request to place his reporters on the frontline in Afghanistan.

“When you turn on the television and you see pictures of journalists in major cities reporting on the war, the average American thinks that these people are covering the war. They are miles away, and in some cases hundreds of miles away,” he said.

“A member of the mainstream media should have filed this lawsuit instead of me.”

But free speech for Flynt was also maliciously absolute — and consumed notions of slander. When conservative commentator SE Cupp suggested defunding Planned Parenthood, she found her image photoshopped into fellatio scenes in print.

“I’m able to publish this because of the Supreme Court case I won in 1984, Flynt v Falwell,” Flynt said, referring to the landmark decision that the right to parody public figures is protected by the constitution.

He undoubtedly found buyers for his freedom pitch but many thought he was full of shit.

The nature of the magazine also made it predictably hard to take seriously as an intellectual force. Or, for some, to look past the smut.

Noam Chomsky, cherished American intellectual and linguist, appeared in a Hustler Q&A but later castigated his interviewers for tricking him into the sit-down. In an uncharacteristically puritanical rant against porn (suggesting viewers have a “problem”), he claimed the “disgusting journal” was one of the hundreds to reach out to him for media comment and it was not obvious who they represented.

To prove his innocence, he said he was similarly led astray by a German neo-nazi magazine, the pages of which he unwittingly graced. (The neo-Nazis were at least considerate enough to send him a transcript before publication — which Hustler did not do.)

The death of the printed word

The paradox of 20th-century adult magazines is they would be simultaneously more and less accepted if released today. There is nothing in those pages that could shock us — not our society that has been dragged to humanity’s depths on the dark web. And yet we would revile the paternalistic ideas and attitudes they espouse.

Hefner’s death in 2017 was greeted by tall columns of the media’s favourite type of eulogy — the “complex legacy”. He pushed sex into the mainstream and used it to get rich; pushed to liberate the female form from society’s shackles and exploited it in his pages; he was a gentleman’s gentleman and a flagrant chauvinist.

The dirty magazine, too, will get a nuanced epitaph.

What ultimately happened to the magazines in this essay is a story we all know. Like almost all others, they were slowly ground down by digital media. As news and other content became a click away, the appetite for printed products waned. Those that survived, and remain relevant today, did so by adapting to an online medium.

For an entity like Playboy, that was a fraught ask. Glossy, tangible pages offer curation. The opportunity to take the reader on a journey; one that can reasonably include all of Picasso, Nietzsche, jazz and sex.

The internet simply doesn’t work like that. Content is pigeonholed and users are specific in their intentions. This has got exponentially worse, to the point where, today, most media houses recognise that traffic is more likely to come from a social media link than visits to their front page.

And then there is porn. Whether you believe those magazines are hardcore, softcore or somewhere in between, the unmistakable fact is that there are far easier ways to look at naked humans on the web.

Playboy, Penthouse, Hustler and others tried to find their way in the new ecosystem, pushing, and sometimes reversing, the boundaries on the type of content they produced. But, along the way, their identities became mangled. They no longer stood for something and so could say nothing of consequence.

The era of selling sex by buttressing it with words from society’s greatest minds was over.

Intuitively, that seems sad. Which is not to say that any of these products were net positives. None of them are easy to defend — good luck to anyone that tries. But our knowledge economy flourishes when its players are as diverse as possible.

Not only were editors willing to invest in writers and thinkers, they delivered their work to a unique audience. What we broadly call the sex work industry is worth untold billions a year. It’s a pity none of those dollars land in the pocket of the wordsmith any more.

Luke Feltham is the Mail & Guardian’s acting editor-in-chief.