Snapchat celebrity and Nigerian Barbie, Bobrisky, poses on November 7, 2016 in Lagos. (Stefan Heunis / AFP)

In 2014, the former president of Nigeria Goodluck Jonathan passed into law a Bill that became the Same-Sex Marriage Prohibition Act. The passage of the law gave way to heightened attacks on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer (LGBTQ+) people by mobs who said they were working for the president.

Over the past six years, the law has led to varying levels of state-sanctioned violence such as the arrest of 47 gay men and their subsequent trials, and the continued harassment and arrests of queer people. They’ve had to hide in spaces that were considered safe — bars and clubs that catered for queer people as well as the homes of activists, until they came under regular attacks and heightened scrutiny.

Despite being stifled under this homophobic legislation, queer people’s effect on popular culture is still evident. An example is Bobrisky, a media personality and openly trans woman who has called herself “the most talked-about”, and with good reason.

Since becoming a noteworthy fixture in the media, hardly a week goes by when Bobrisky isn’t topping the trending topics on the Nigerian subsection of Twitter. She has inspired popular slang and been the subject of many reaction videos and memes. Nigerian singers such as Odunsi (The Engine), of the alte-music subgenre, have drawn inspiration from queer culture for their music videos. Fashion brands, including Orange Culture and Maxivive, have challenged gender and sexuality norms in their designs, echoing the spirit of global queer activism and resistance.

But being visible is not always a good thing. The art that features queerness, especially in the mainstream movie industry of Nigeria, has perpetuated homophobic stereotypes arguably informed or influenced the Act.

In 2010, before the Bill was signed into law, Moses Ebere released Men In Love, a direct-to-video movie about a young married couple (Whitney and Charles, played by Tonto Dikeh and John Dumelo), whose rocky marriage is shattered when they meet an enigmatic gay man, Alex (played by Muna Obiekwe), who attempts to seduce and eventually rapes Charles. For the duration of the movie we are introduced to several gay men, each a similar stereotypical character with little depth beyond an overdone drawl, a flair for the dramatic, a love for wanton debauchery and, perhaps the most damaging of all, the reduction of a romantic homosexual relationship to sex and money.

The characters are hollowed out. Their humanity, and anything beyond being sex-driven maniacs creating chaos, is removed. They are empty shells performing what some cis-heterosexual people believe is homosexuality.

Another film, Emotional Crack — released in the early 2000s and starring Ramsey Noah, Stephanie Okereke and Dakore Akande — tells a story of a loving couple whose lives are ruined by a lesbian who seduces the wife and sets out to destroy the marriage. Both Men In Love and Emotional Crack — and most Nigerian movies that feature queer characters — tell a story of how queer people plan to destroy the sanctity of marriage and are beautiful people you can not trust because they want to turn you into a queer person and destroy your life.

The undertone of the films is a warning to parents that this is what your child will become if they “choose” to be homosexual. The view that gay men seek out straight men to force their way on them has led to many straight people avoiding people they suspect or know to be queer and, in extreme cases, pre-emptively attacking them.

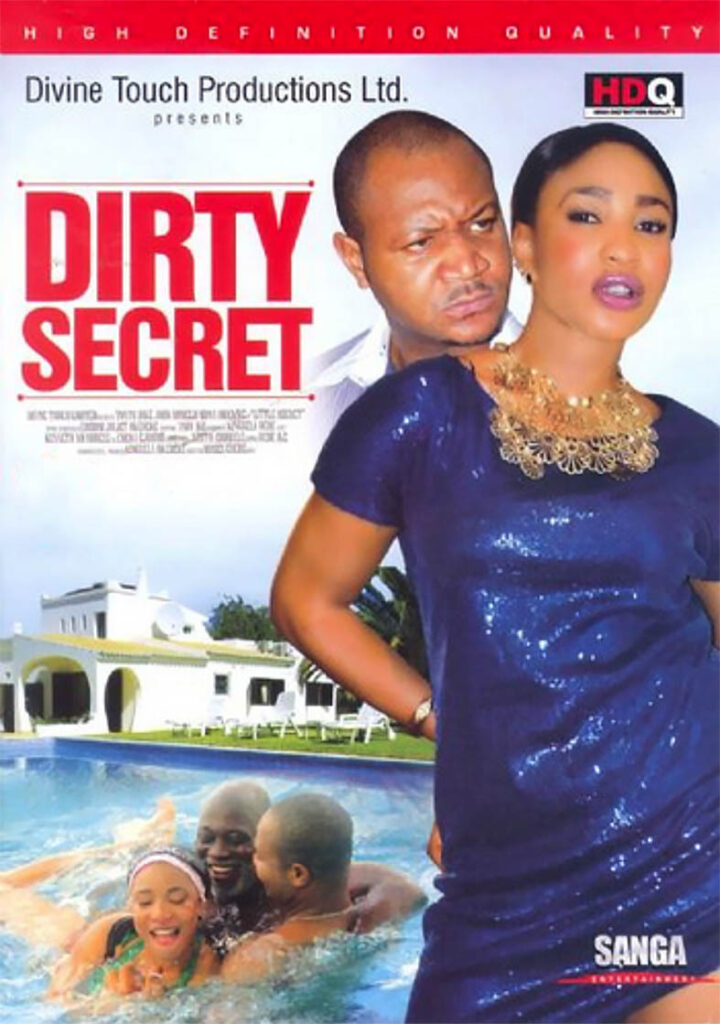

The 2010 film Dirty Secrets, which stars Obiekwe and Jibola Dabo with Obiekwe playing Ken, a bisexual gigolo, repeats the tropes of hedonism and the reduction of homosexual relationships to sexual trysts. It plays to a particular idea that government officials often use to justify the Act and garner support for it: same-sex attraction is a “gateway sin” that leads almost directly to other deviant sexual relations such as paedophilia and bisexuality.

The argument is: if the lawmakers legalise homosexuality then they have to legalise every other form of “deviant” sexual relationships. In Dirty Secret, a film about incest, we watch as Ken initiates a sexual relationship with Otumba (Dabo) and eventually one between himself, Otumba and his daughter Pandora (played by Dikeh). The subtext is clear: this will be the world we will live in if homosexuality is legalised. Cue angry mob fighting what they believe is a righteous fight against an immoral world.

Most of these movies were released at a time where the country did not yet have laws that criminalised queerness and shaped the way Nigerians view queer people — cursed or possessed, deliberately trying to destroy heterosexual relationships, deadset on converting straight people. By the time the national conversation turned to whether same-sex marriages should be legalised — and if queer people should have rights — the answer was a resounding “no”. Not to be discounted is Nollywood’s role in helping to push for the demonisation of queer people.

What then is the future of queer cinema in a country like Nigeria? Over the years, Nollywood has witnessed growth, especially of more progressive films. Misogynistic storylines for the bigger-budget films have become less common and obvious. This makes one wonder: Have queer stories experienced this growth as well? Will they? Can we expect more movies with queer characters being more than stereotypes? The answer is not nearly as straightforward as one might hope.

Producer and director Mildred Okwo believes the younger, bolder generation of Nigerians makes possible the positive representation of queer people.

“A lot of young people that are gay and lesbian are living their lives and I think if that continues to happen, writers will write about what is happening around them,” she says. “That being the case there will be a more positive representation.”

But Okwo also points out that the current state of the industry is a result of veterans in Nollywood care more about portraying society as they think it is, rather than how it should or could be.

“Nollywood rarely is forward-thinking,” Okwo says, “People rarely realise they can create worlds with movies and create them as they want them to be. So when we have people that are more creative, that are forward-thinking, that look into the future and see what will be in the future and depict them in films today, then we’ll have more positive LGBTQ+ representation.”

In recent years, several short and feature films with queer leads telling more rounded and humane stories have been release out of Nollywood. But many of these movies do not enjoy the mainstream spotlight. Yet the mere existence of these films means a mainstream queer story might be in our near future.

Asurf Oluseyi, who has worked on several of these films, says: “No one can represent you and tell your story better than you can. Chances are, you will help others and yourself in the process. And I think [queer people are] aware of this, and lately they have been creating some content [for] short films and some feature-length films.”

But it isn’t that easy. Securing funding for these movies is a hassle and when that is done, the movies may be banned, as happened in Kenya. Wanuri Kahiu’s Rafiki was banned because of its homosexual storyline and accused of promoting lesbianism. The Kenyan Film Classification Board asked the director to change the movie’s ending, stating it was too hopeful and positive for a film with homosexual leads.

It is not hard to imagine this being the story in Nigeria. But as streaming becomes the go-to and with Netflix setting up camping in Nigeria, the answer to the question of whether Nigeria can expect more movies in which the queer characters are more than stereotypes could be “yes”.

This feature first appeared in The Continent, the new pan-African weekly newspaper designed to be read and shared on WhatsApp. Get your free copy here.