Drawn Lines invokes a double meaning of drawing as the prevalent medium of expression in the show, but also that of marking political demarcations. (Judy Seidman) (Delwyn Verasamy)

Public interlocutions have somewhat disappeared from our local newspapers, more so those that pertain to the art and cultural sphere. This is a cause for concern, because de-popularisation of a critical and robust exchange blunts the capacity for a discerning public culture. So I was delighted when, first, artist and activist Judy Seidman responded with a challenge to my views, and then again when writer and scholar Njabulo Zwane joined the discussion to offer some insightful clarifications of his own. I will, in that spirit, delayed as I may be, confine my remarks to Seidman’s provocations.

Seidman’s reply picked up three points from my review — namely, my accusatory scepticism about her personal collection of the Medu Art Ensemble works; what I can only refer to as the dominance of the workerist aesthetic versus its racial underside; and, lastly, her engagements with the feminist collective, the One in Nine Campaign. In her earlier draft, which she had emailed to the paper and also to me, Seidman writes:

“The ‘personal collection’ was accumulated by me as a member of Medu — not as a ‘collector’ in the private, commoditising sense; I am sure that you, like most writers, also keep a box of work you have been involved in. Perhaps the real concern should be, not that I have keep kept these, but that 30 years after the events, and two decades post-1994, there is still no state-supported arts gallery or museum or archive that collects, preserves, or publicises Medu’s historic contributions to our aesthetic and cultural discourse (Freedom Park and the Mayibuye Centre have near-complete collections of Medu posters, as does the NGO South African History Archives; none of these has a full collection of Medu newsletters, nor of the papers presented at the 1982 Gaborone conference). These papers are not available in the cloud, or in any public space.”

I have italicised the sections above for the reader to pay attention to the tone and what is implied here. Whether deliberately or not, Seidman chooses to confine my interests in her collection as querying only her “newsletters” and “articles” and not the posters — items attached to her name and through which she also draws a cultural capital — as well. Early last year, I happened to visit the exhibition, The People Shall Govern! Medu Art Ensemble and the Anti-Apartheid Poster (2019) hosted by the Art Institute of Chicago, Illinois. Some of these items were labelled as belonging to the Judy Ann Seidman collection, as has also been the case with a number items in various other exhibitions, catalogues, and books that also credited the same collection.

The People Shall Govern (Medu Art Ensemble) (Judy Seidman) (Delwyn Verasamy)

The People Shall Govern (Medu Art Ensemble) (Judy Seidman) (Delwyn Verasamy)

But what is really contained in this question? How do some things, said to be belonging to Medu, become itemised as belonging to one member’s collection? Of course, documents such as newsletters and other ephemera aren’t part of my concern here. What I am querying is how, for instance, essential items such as 1982 Culture and Resistance conference proceedings/papers, and collectively realised silkscreen posters, can be reduced as personal property of a single member, à la the Judy Ann Seidman Collection? What this tends to do is simultaneously appropriate and negate the labour of others, such that they become extensions of the figure to whom the collection “belongs”.

This personalisation, I argue, can neither be cheapened by uncritically, if not evasively, likening Medu’s singular practice to one any collective or group can or should do, nor easily avoided by attributing the blame to public institutions. It should also not be lost on us that when an item is referred to or credited as coming from a particular collection, that such symbolic gesture implies an absence of transaction and value (it need not be money). The idea that Medu’s works are reduced to an individual’s personal property, and have been for so long, is what I find bothersome here.

This (for me) resonates with the troubling concerns about acquisition practices of (South) African cultural and intellectual archival material by private hands and institutions alike. The recent debates about Western cultural institutions returning African art objects acquired during colonial expeditions and wars had largely been met by an arrogant, Western, dismissive tone, implying that African states do not have adequate facilities sophisticated enough to care for their own historical objects. Except for a few institutions who have relented to the pressure, the world remains convinced in its authority over Africa and its art objects.

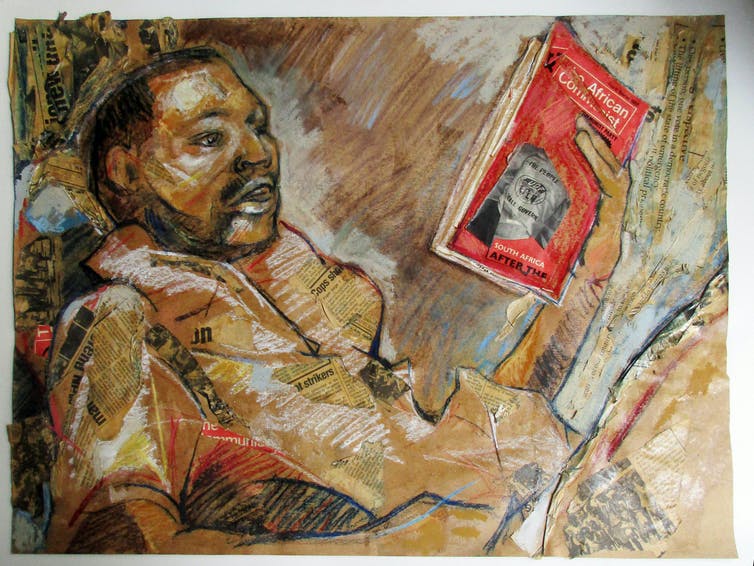

Comrade portrait (Serge) (Judy Seidman)

Comrade portrait (Serge) (Judy Seidman)This is not to argue that Seidman’s collection has been acquired in a similar way, but to highlight a general tendency in the West. Seidman’s collection, however, does raise questions attendant to this tendency, about who gets to keep historical materials on behalf of others and who determines this? Certainly, Seidman’s foresight has to be commended against the historical philistinism of the ruling party. Such preservatory regard for cultural memory has come in handy for scholarly research and is ultimately helpful in broadening the cultural landscape beyond the solipsism of contemporary art. But the justification that there are no public institutions capable of housing such material is disingenuous. Didn’t fellow comrade Sergio-Albio Gonzalez donate some of his Medu posters and other movement paraphernalia to a local public institution? If the historical purpose of Medu artists was to learn and teach others, doesn’t the digitisation of some of these written materials and publications circumvent the culture of institutional privatisation of the commons?

As concerning as the financial state of our public institutions is, the idea that a Judy Seidman collection “loans” the Medu cultural archive (even to the same institutions) seems rather counterintuitive. One would have to agree with anti-apartheid artist and activist Thami Mnyele, who wrote in an article for Staffrider (“Thoughts on Bongiwe Dhlomo”) that “the system of fragmentation, the tendency towards individualism, exclusiveness and isolation is as moribund as that of divide and rule”.

It is perhaps in this sense that Seidman’s justifications not only resonate with those of Western cultural institutions keeping African art objects under spurious claims, but also remind one of white people who refuse to give back stolen land on the basis that black people don’t have the means to care for it. In the end, there’s a continuity between this self-imposed supervisory entitlement and the historical gesture of colonial occupation. Clearly Seidman sees no irony in her justification, let alone in the personal proprietorial marking of the collection as “hers”. What begins as a prescient intention to safeguard the archival historicity of cultural resistance for the future, degenerates into an act of self-preservation in the name and manipulation of that collective will.

This brings me to the next point. White people have amassed symbolic and financial dividends from black subordination, including their resistance cultures. The pretensions to befriend and fight on the side of black people against oppression has, in the worst cases, contributed to the obfuscation of the totality of white power. In an instant, black struggles would pay lip service to racial subjugation, and veer off into fighting for the democratisation of that same oppressive paradigm, such that the road to liberation is one that leads to democracy first, and not to decolonisation and restitution. Put differently, the culture of resistance constructs the subjectivity of “a people”, that is on one side parasitic to the specificity of the black suffering and, on the other, presides over that suffering’s ensemble of questions to ensure the preservation of the racial order.

What does this have to do with Seidman? In her article, Seidman argues that my labelling of her work as inflected by a workerist or white leftist orientation misinterprets what she and, by extension, Medu artists were doing. She argues that these labels, which Medu apparently repudiated in the 1980s, referred to white activists who detached themselves from the liberation movement. Granted, the movement did not separate race, class and gender in the apartheid matrix, but its work foregrounds workers because they were the “leading political force”. That trade unions and other worker formations have been historically dominated by white radicals who have been pumping money and resources into them should alarm us about the source of that prominence.

Personally, I wasn’t too concerned about what labels enticed or embarrassed white activists, but I was rather interested in the kinds of political visions that dominated the liberation agenda. I had critiqued the category of work as the lens within which the black historical experience was confined, arguing instead that, on close scrutiny, the doctrinal framing of the black as primarily “the worker” obscures the colonial nature of their oppression. The unresolved tensions between class and race, let alone gender, were such that they analogised the relations of white over black. Here the class conception of the black reality becomes rendered as “capacious”, such that it allegorises race, or diminishes it to an epiphenomenon, in the dialectical progression.

The poster announcing Cosatu’s 4th congress in 1991. (Judy Seidman)

The poster announcing Cosatu’s 4th congress in 1991. (Judy Seidman)

For the settler colonial paradigm, race is the constitutive feature through which matters of life and death — and even of aesthetics — are mediated. In other words, the very notion of the black working class and the attendant gender dynamics evolve out of the racial structure and logic fundamental to the very idea of the South African polity. Note: I do not conceive of gender as an exclusive domain of women, as I also do not deny the historical specific experience of humiliation and violation black women continue to endure. The disappearance of the victor and vanquished dynamic in the lexicon of resistance culture prefigures the telos of the liberation struggle. And it is here that I pick up “exoticism”, but not simply by way of the hackneyed visual troping of the native as a naive extension of the flora and fauna, as perceived by the colonial ethnographers. Instead, I try to gesture to a subtle continuity in content that in form differs.

That Seidman’s artworks portray black people with agency and commitment is what troubles me about the commonplace treatment of the notion of the cultural worker. That is, as a category that appears self-explanatory — and, therefore, whose theory of commitment and agency never comes under interrogation. By examining the raison d’être of work as a political category through which to thoroughly grasp the black condition, one inevitably sees through its attenuated layers the conceptual bankruptcy mobilised as gospel, a devious agenda to hold black emancipatory power at bay. Thus, a broader study of exoticism speaks to the problem of the decorative utility of objects (read black people), whereby the function of appearance has an asymmetrical relationship with how things really are. Conceding to the exterminatory logic of apartheid in form but never in content merely turns black people into objects for artistic representations and consumption, but not masters of their destiny — a representation in symbol but never in substance.

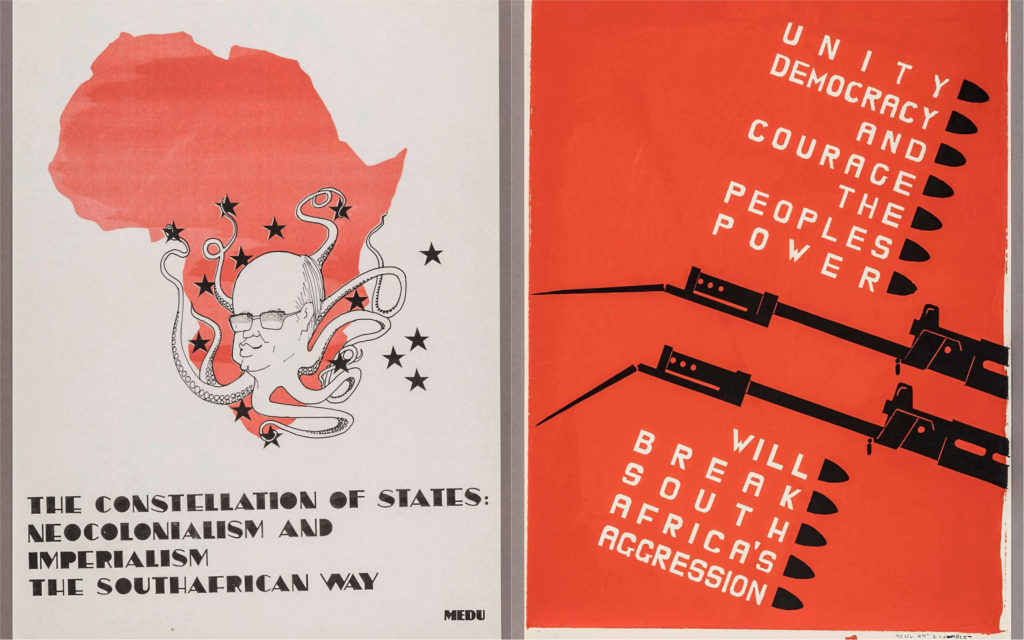

Constellation of States (litho), Gaborone, 1979 and The People’s Power will break South Africa’s Agression, (silkscreen) Gaborone, 1983. The posters, by other Medu artists, do not form part of the Drawn Lines exhibition. (Thami Mnyele and Gonzalas for Medu Art Ensemble)

Constellation of States (litho), Gaborone, 1979 and The People’s Power will break South Africa’s Agression, (silkscreen) Gaborone, 1983. The posters, by other Medu artists, do not form part of the Drawn Lines exhibition. (Thami Mnyele and Gonzalas for Medu Art Ensemble)

In recent studies on anti-apartheid resistance iconography, United States-based cultural historians (who have de facto become the domineering voice in this particular historiographic landscape) have made the inclusion of white people to Medu a political virtue. That Medu has been parachuted into a singular project in South African art and cultural history, whose memory and activities have been kept alive more than its predecessors, is hardly a surprising feat. What tends to be really confusing, at least in these historical texts, is the ambivalent place Black Consciousness is given.

On one side, its cultural organisations are repudiated as a “narrow nationalism” primarily for excluding whites, thereby making Medu their progressive successor. On the other side, Black Consciousness is fully in operation within the non-racialist precincts of Medu, articulated beyond its nationalistic invariance. Under this revisionism, Black Consciousness no longer finds the Freedom Charter as “objectionable” as Steve Biko, the founder of the Black Consciousness Movement, once argued, but becomes an extension of it.

I raise this as an aside, to a point Seidman makes questioning my claim about white people being “default tutors” in nonracial political setups. She asks if I am suggesting whether high-ranking names like Mnyele and poets and political activists Wally Serote and Willie Kgositsile “passively accepted a working environment in which ‘white people become the default tutors to black people’”? And, typical of the white left, which she excoriates as separating itself from the movement, Seidman proceeds by way of a self-effacing attitude. On one side, she distinguishes herself from the private collector, the white left, artist and even the tutor; on the other side, her practices suggest the contrary. The white radicals’ trick of the trade is to dissolve into “the people” in form while keeping a firm grip on the steering wheel.

Keorapetse Kgositsile, a member of the Medu Art Ensemble, was the country’s poet laureate.

Keorapetse Kgositsile, a member of the Medu Art Ensemble, was the country’s poet laureate.This question also returns us to the issue of agency. By 1979, not only was white inclusion a recent “strategic” resort for the ANC after its Morogoro conference in 1969, it was also a position geared towards exterminating the long shadow the Azanian tradition cast over the white left and liberals alike in the wake of the 1955 Freedom Charter. The exclusion of white people by black political formations had severe consequences for their growth, considering that white radicals in all areas of life had access to personnel, finance, research and institutional advantage. Mobilising their resources against Black Consciousness made sure that what Biko and his comrades had done in excluding them in the early 1970s never repeated itself in the 1980s and beyond.

Thus, the mushrooming and international recognition of Medu depended on dispelling this shadow, what Gonzalez (describing the failed initial attempt by Serote and Timothy Williams’s Pelindaba Cultural Effort) calls “a group that did not flourish as expected due to its ‘narrow’ approach to membership” in Thami Mnyele Medu Art Ensemble Retrospective. Similarly, Mnyele advanced a caricature of Black Consciousness-aligned cultural movements’ exclusion of white people, reducing its criticism of white allies to empty talk because it was no “less hurtful to be slapped in the face by a black policeman than a white one”.

“White supremacy,” argues Tamara Nopper in her essay, The White Anti-Racist as an Oxymoron, “is not just a series of practices or privileges, but a larger social structure and a system of domination that overly values and rewards those who are racialised as white.” That Black Consciousness had already advanced a convincing take on the intra-black violence and the expansive nature of anti-black racism, didn’t matter to Mnyele. It was also prevalent to hear former Black Consciousness adherents repeating after their new leaders that Black Consciousness was an inane stage in youth that prepared them for their political maturity: the ANC. This infantilisation of Black Consciousness is the direct derivative of “class”, ipso facto the ruling class, in which Black Conscious was presented as a lack that one is destined to outgrow. Being an adult, much as being sentient, is after all associable with white people.

One here has to differentiate between performative and substantive agency. What often appears as black agency in non-racialist setups in a racist world, is the artifact of a self-effacing dogma operating in disguise. It is this same invisible hegemonic labour that white radicals undertake in shaping not only the political narrative of the oppressed, but also securing its power, over and over again. Thus, when Seidman asks whether I had spoken to the women in the One in Nine Campaign or “engaged” the pictures before arriving at my conclusions, it wasn’t a surprising inquiry.

However, one must admit that this is a peculiar challenge coming from the artist: that, instead of dealing with the consequences of what they have offered, she asks reviewers to conduct field research. Considering the subtle self-vouching assertiveness and the racial dynamics at play in the show, the likelihood of a contradictory statement might very well jeopardise any black woman who dares to speak out of turn. We need not to pretend that a black woman’s unflinching critique within the rigged and coerced nature of that setup isn’t an act of self-sabotage. I was hardly astonished. After all, to say black speech is coerced doesn’t mean an absence of sound or gesture but an interdiction to truly articulate the structural restraints governing that relation.

As a result, what concerned me about the nature of this collaboration, wasn’t anything different from what concerned me in the rest of Seidman’s pictures; the conspicuous presence of black people and absence of white people except as recorders of the formers’ bodies, strife and existence. Seidman’s absence in the visual plane as collaborator raises doubts about the nature of, if not her very capacity in, the collaboration. This absence is neither explained nor easily decipherable. We search in vain for the missing link in the collaboration, as if we’re ghost hunting. Symbolically, the ghost takes on the form of the director, the artist and the brains behind the act — one that is justifiable by installing the photomontage as an extension of the exhibit.

In this way, like characters in an extended album, black peoples’ voices, stories and experiences appear only as part of the auteur’s elaborate cinematic unravelling. Their speech is entangled in hers, as hers, through her. We see them, but hear her. Black people saturate the visual, languishing under their sorrows, but the structure, the frame, from which we view them is a borrowed one. It anthropologises. This disregards not only these women’s subjectivities, but also the very pretensions of collectivity, which we’ve already established that Seidman uses as a magic wand to hide an insidious, self-interested spirit.

We should be wary of taking theories of commitment and agency as self-evident; we should instead question their unspoken assumptions as we also question the motivations attendant to them.

An earlier version of this article was edited for factual accuracy.