Walking the tightrope: Finance Minister Tito Mboweni makes tough budgetary decisions. (Dwayne Senior/Bloomberg via Getty Images)

The government is adamant that a freeze on public sector salaries for the next three years is essential to claw back fiscal stability, but the proposal has angered labour, who argue that the treasury has failed to honour the increases negotiated in the 2018 wage agreement.

Mugwena Maluleke, labour federation Cosatu’s chief negotiator in the drawn-out wage talks, likened the announcement of the freeze to “a declaration of war”.

And Reuben Maleka, the assistant general manager of the Public Servants Association of South Africa, said the government’s announcement undermines collective bargaining. He added that the association would “fight fire by fire” for the 2018 agreement to be fulfilled.

Zwelinzima Vavi, the general secretary of the South African Federation of Trade Unions said corruption is happening in government and the treasury should not be punishing workers for the lacklustre economy.

He said that instead of introducing cuts, the treasury should have introduced a wealth and solidarity tax.

In Wednesday’s medium term budget policy statement (MTBPS), Finance Minister Tito Mboweni said the intention was to cut non-interest spending — mainly the public sector wage bill — to trim the country’s national debt and narrow the budget deficit.

According to the treasury’s estimates, the cuts would result in a decrease of the budget deficit from 14.6% of gross domestic product (GDP) in 2020/2021 to 7.3% by 2023/2024. If this is done, it is projected to stabilise the gross national debt at 95.3% of GDP by 2025/2026. The reduction of non-interest spending could save the fiscus R300-billion.

Maluleke took another swipe at Mboweni’s spending cut proposals, saying that his fiscal austerity stance is not addressing the issue of economic growth and recovery. He said it will only prolong the country’s recovery.

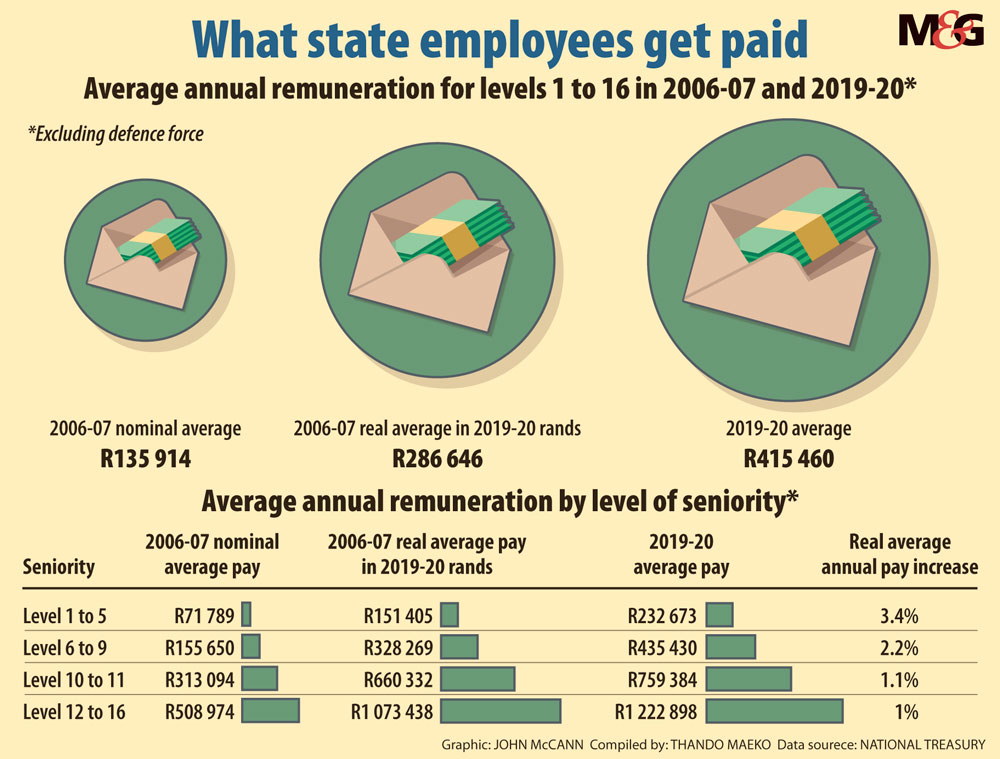

Over the past 14 years, the government’s workforce has increased by 16%, from 1.15-million to 1.33-million, according to the treasury’s data. Over the same period, the average salary of a public sector employee ballooned from R136 000 to more than R415 000 — a 45% increase.

The increase in the average salary is largely the result of the introduction in the late 2000s of occupation-specific wage dispensations, annual cost-of-living adjustments to basic pay and a system of wage progression where junior employees are promoted.

Data from the treasury also shows that 75% of the public servants employed in 2020 (excluding members of the South African National Defence Force) have been working for the government for at least a decade. Of these, 5% have received real decreases in average remuneration of at least 1% over the period, while 5% have received increases of up to 19%.

Half of all long-term public servants have received real increases of more than 44% over the past 10 years; 25% have received increases above 71% and a small fraction have seen increases of more than 1 000%, according to the treasury’s document.

Mboweni said that in the past five years, public sector employees have received above-inflation increases of 7.2% a year on average.

Speaking at a media briefing shortly after presenting the mid-term budget policy statement, Mboweni said he is confident that the “conversations” between the department of public service and administration and the public sector unions will result in a positive outcome. But, he added, the economy is in a “bind”.

“We are in a fiscal framework that we need to protect … and we have to manage our finances much better,” he said. “We can’t break the fiscal framework [and] something has to give.”

In illustrating the tightrope Mboweni needs to tread, the mid-term statement acknowledges the contributions of public servants and commits to providing fair and sustainable compensation. But the treasury said that in light of state borrowing funding consumption, the wage-setting process has become divorced from economic reality — hence the government proposal for a three-year fiscal consolidation.

The economy is expected to contract by 7.8% in real terms this year, and the 2021 outlook is more uncertain, according to the mid-term statement.

Job losses have been particularly severe. This has led the treasury to propose a five-year fiscal consolidation that enables continued support for the economy and job creation.

“The fiscal measures outlined in this MTBPS will bring the state’s debt burden under control, realign the composition of spending from consumption towards investment, and improve investment conditions by lowering the cost of capital,” reads the statement.

But the unions have not responded well. They took the government to court over the stagnation of wage increases prior to the policy statement.

The question is, what happens if the court rules in favour of the public sector unions and the government’s envisioned wage freeze does not materialise?

Dondo Mogajane, the treasury’s director general, said at the media briefing that the government “will cross that bridge when [they] get there”.

He added that the weak economy requires that “pain is felt” by not only the working class but throughout the public service.

Maluleke said the government’s approach of making announcements without consulting them dismisses collective bargaining. “You cannot, therefore, predetermine the outcome of collective bargaining,” he said, adding that it seems the unions need to go to the bargaining council to beg and not negotiate.

Isaah Mhlanga, the chief economist at Alexandra Forbes, said he expected the unions would not take the proposed wage cuts lying down.

He added that the treasury’s proposals would not work because the matter is already before the court.

Izak Odendaal, the economic investment strategist at Old Mutual Wealth, said the unions may adjust their demands and ask for lower wage increases than what was agreed to in the 2018 agreement.

Thando Maeko and Tshegofatso Mathe are Adamela Trust business reporters at the Mail & Guardian