Lifeline: People queue at the labour department’s offices in Johannesburg to apply for UIF benefits during the Covid-19 pandemic. (Delwyn Verasamy/M&G)

The Covid-19 temporary employer/employee relief scheme (Ters) is set to be extended, offering hope to workers hit by the current two-week lockdown.

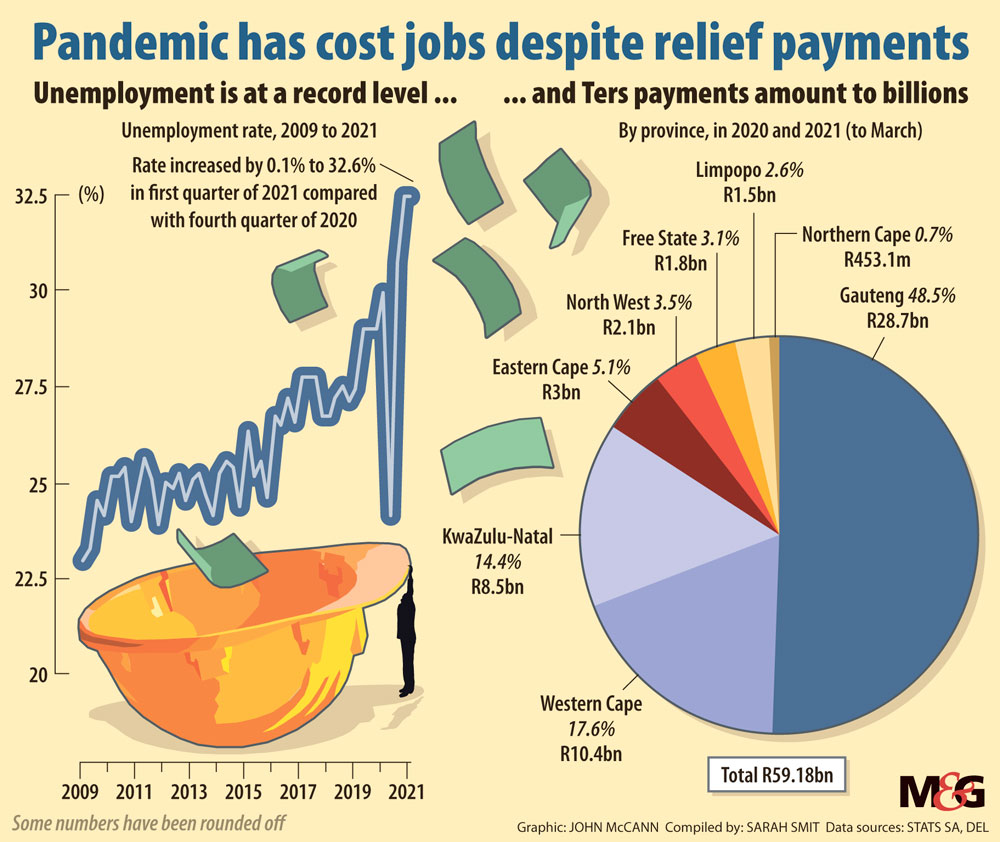

The extension of the scheme — which has provided more than R60-billion in income support to furloughed workers over the course of the pandemic — comes despite concerns about the liquidity of the Unemployment Insurance Fund (UIF). The fund has had to withstand the added strain of administering Ters payouts as the country reels from a spiralling jobs crisis.

The UIF is the main safety net for workers facing unemployment, which reached record levels during the Covid-induced economic downturn and has shown little signs of waning.

In the face of these pressures, the UIF has managed to find the money needed now, as the third wave of the pandemic poses a new threat to lives and livelihoods.

According to UIF spokesperson Makhosonke Buthelezi this has been made possible for two reasons: Ters payouts tapered off at a faster rate than expected last year and the fund realised higher-than-anticipated investment returns as a result of economic recovery in 2021.

New conditions

Last week, during a national coronavirus command council briefing, Minister of Employment and Labour Thulas Nxesi said paying out Ters benefits “has always been something of a balancing act, where we have to look at the affordability versus the need”.

Covid-19 sent South Africa’s unemployment crisis off the deep end. In the first months of the initial lockdown at the beginning of 2020, 2.2-million South Africans lost their jobs, according to Statistics South Africa’s quarterly labour-force survey.

And, despite signs that the country is on the path towards economic recovery, jobs have not bounced back. According to the most recent data, in the first three months of 2021, the unemployment rate reached 32.6% — the highest since the quarterly labour-force survey was launched in 2008.

The current lockdown, announced by President Cyril Ramaphosa to contain the spread of the doubly contagious Covid-19 Delta variant, has once again left workers in the alcohol and hospitality industries out of pocket.

To address these “new conditions”, Nxesi said, UIF management had been locked in discussions with actuaries to find the surplus funds needed for more Ters payments.

The fund currently cannot give an indication how much the two-week lockdown will cost it, Buthelezi told the Mail & Guardian this week. But, he said, in the worst-case scenario 100% of employers who applied during the last lockdown (16 October 2020 to 31 March 2021) would apply again. In this scenario, payouts would amount to R9-billion.

Depending on the rate of applications, the UIF could end up paying out between R1.4-billion and R3.5-billion for every week the lockdown is extended, Buthelezi indicated.

Buthelezi noted that the UIF will continue to assess its capacity to deal with further waves of the pandemic as claims progress.

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

Running on empty

Earlier this year, the M&G reported that the fund will run an average deficit of R19.7-billion as it shoulders the burden of the Covid-19 jobs bloodbath.

According to the treasury’s budget review, tabled in February, the UIF is expected to pay out benefits amounting to R101.9-billion in the 2020-21 financial year. This is a 533% increase compared with R16.1-billion paid out in 2019-20. Over the next three years, the UIF expects to pay out R92.9-billion — a 155% increase compared to the amount the fund paid out in the three years before the pandemic.

Last year, in response to a parliamentary question, the UIF set out several scenarios for the fund’s liquidity if unemployment continues to soar and it had to keep on doling out additional relief.

The UIF’s actuaries found that if the unemployment rate peaks at 41.4% and Ters benefits cost R48-billion, the fund will become financially unsound as insurance capital — required to “borrow from the future” — is depleted. However, sufficient funds should be available to pay claimants on a “pay as you go” basis. In this scenario, the fund could return to financial soundness in 10 years.

In the worst-case scenario, if the unemployment rate peaks at 53.7% and Ters benefits cost R48-billion, all accumulated credits will be depleted, and the UIF would also need to borrow against beneficiaries and service providers to pay claims.

The UIF has already surpassed its initial budget by almost 30%, but the country has not yet neared the worst-case unemployment rate.

The fact that the fund can pay now does not mean it is out of hot water. Any further extensions of Ters payments will impede the UIF’s ability to pay normal claims for unemployment and parental leave, Buthelezi said.

“The fund has already forgone all other technical reserves, except the unearned premium reserve [worker credits] and those required by legislation to make funds available for the payment of Covid Ters benefits,” he told the M&G.

“The fund has a responsibility towards its paying clients to retain the unearned premium reserve to ensure funds they contributed are available when they submit a claim.”

Buthelezi also noted that, in the current economic conditions, the UIF’s investment returns may be wiped out faster than they can be generated. The fund’s “dwindling investment portfolio is losing its capacity to generate exuberance”, he said.

“However, the fund is sympathetic to employers and employees’ situations and will reassess its financial soundness continuously to determine the availability of funds to assist during the pandemic.”