As South Africa moves to lockdown level three, the Eastern Cape is struggling to keep up with contact tracing and testing for Covid-19. (John Moore/Getty Images)

As South Africa moves to lockdown level three, the Eastern Cape is struggling to keep up with contact tracing and testing for Covid-19.

The provincial government says the number of Covid-19 cases increased rapidly when the lockdown level moved from five to level four on May 1.

Concerns about how the province was handling the pandemic resulted in Health Minister Zweli Mkhize having to intervene towards the end of April. Among other steps, he sent a team to assist with the tracing, screening and testing of people, particularly in the Nelson Mandela Bay metro.

But the problems remain. Several Covid-19 hotspots are in the Eastern Cape.

Across the province, a failing contact tracing system mean the province is struggling to contain the spread of the disease. This is as the health department says the pandemic will peak in July and August nationally. For people in the Eastern Cape, this failure has meant people are dying.

The World Health Organisation says contact tracing — identifying, assessing and managing people who have been exposed to a disease to prevent onward transmission — and testing are crucial to controlling Covid-19.

But this systematic process seems to be too big a challenge in the Eastern Cape.

According to relatives of those who have died of Covid-19 and those who have tested positive in the metropolitan municipalities of Nelson Mandela Bay and Buffalo City metro and the rural Chris Hani District Municipality, it took more than a week for the provincial government to respond to cases even in circumstances where families had directly reported positive cases.

A resident in East London (Buffalo City) said he contacted the government through its WhatsApp call centre helpline on May 22, yet six days later he had still not received a response.

“I WhatsApped the government online screening and after answering the questions there, the response was that I was high risk and that I should go for a test. But there was nothing about which testing facility I could go to,” said the resident, who lives with his wife and child and wished to remain anonymous.

“I then phoned the toll-free number and I was asked similar questions. The person on the phone told me to continue to take the medication that I was already taking and that I should get a doctor’s referral letter for testing.”

The resident said he then went to Ampath Laboratories on May 25 to be tested and his results came back positive on May 27. His wife had already been told at work to self-isolate for 14 days from May 21.

“My fear was that I might have been exposed to Covid-19, because I had gone to Frere Hospital for three days, taking my sister to the oncology side for radiation therapy. The problem is that the screening process at Frere is very loose. At times when I arrived, there would be no person screening at the entrance and I think I got exposed there,” said the resident.

It is now up to him to self-isolate because the government has still not contacted him.

Two weeks ago, a person who lives in Cala in the Chris Hani district municipality died of Covid-19. More than two dozen people had been in contact with the deceased. These people contacted the government using the helpline and called top-ranking government officials. But it took the government more than a week to trace the contacts.

After much frustration at not getting assistance from the government, one of the people who had been in contact with the deceased self-isolated with his wife in his home village in Lady Frere.

“He has been in the village since. He says the local councillors in his rural village have been supportive. And that he has taken all precautions,” said a person close to the families.

Other members of the group, who have been taken into isolation after nine days of waiting, are being accommodated in B&Bs in the small town of Cala.

In an official document, the Eastern Cape government said there has been a rapid increase in Covid-19 cases during May and there is a backlog in processing test results. This, it says, happened in the seven days after lockdown regulations were relaxed on May 1.

It adds: “The backlog and long turnaround times for the test results in the NHLS [National Health Laboratory Service] laboratory in Port Elizabeth have compromised the public health response to the pandemic. Delays in getting the results from the laboratory led to mistrust [in] the government and public health interventions. Some people received their results after 14 days after their date of collection.”

Provincial health spokesperson Sizwe Kupelo said the government has now declared the Chris Hani District Municipality an emerging hotspot.

He added that areas in the district were hotspots previously and some older people with comorbidities had succumbed to the virus after they had attended funerals.

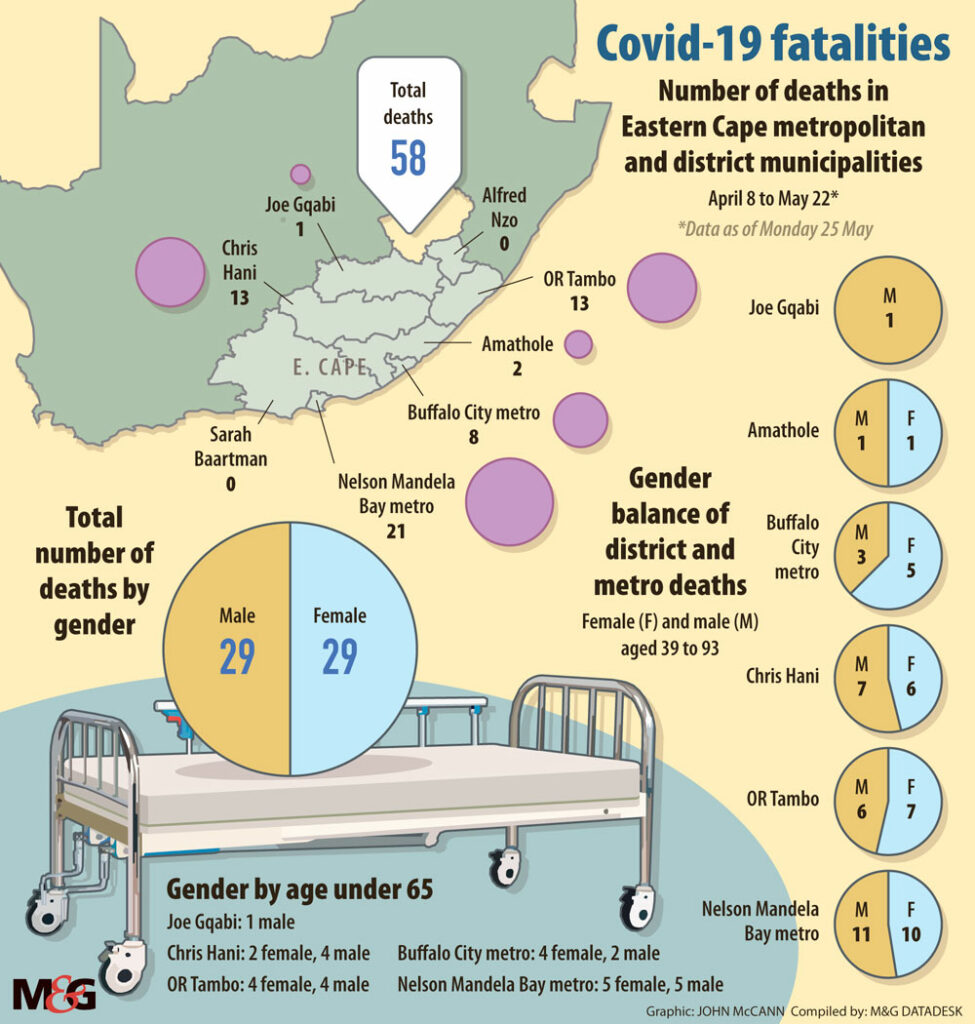

(John McCann/M&G)

(John McCann/M&G)

“The picture changed in May when inmates and officers in Sada Prison [in Queenstown] tested positive for Covid-19, with the numbers surpassing the Emalahleni [in the Chris Hani district municipality] figures.”

Another failure of contact tracing was in Nelson Mandela Bay metro, where a family of nine in KwaDwesi, 20km from Port Elizabeth, made numerous attempts to get assistance from the government after one of them had been in contact with a person who tested positive for the virus.

A relative said she had to contact private doctors to assist with testing.

“The person was already feeling scared and facing a stigma because people in the community were already calling her Nocorona,” she said. “A friend had to mobilise private doctors to go and test the family and she tested positive. There were still no government people that went to that household.”

There are other cases of people claiming that they report their symptoms and only get attention and contacted by the government more than a week later and then wait for their results for another a week.

According to the document: “The number of new cases continues to be detected in these health districts … In Bhisho/King William’s Town there is a gradual increase,” reads the report.

How Eastern Cape Covid-19 patients are dying

An epidemiological report seen by the Mail & Guardian from the Eastern Cape government paints a gruesome picture of how people who contracted the virus have died. The deceased experienced multi-organ failures, kidney failures, cardiac arrest and respiratory failure.

As of Monday May 25, the case fatality rate for the province was 2.2%, but it has since increased to just less than 3%. The majority of people who died were over the age of 50. But there have been cases in which young people with no underlying illnesses have succumbed to the virus.

The majority of the underlying issues were related to lifestyle diseases, which have become a growing problem in the country. The lifestyle diseases prevalent in the province include hypertension, diabetes and obesity.

The document seen by the M&G does not provide patients’ personal information, but does list their symptoms, comorbidities and causes of death.

Of the 58 people who had died by May 25, five people had tuberculosis [TB], five others had HIV, and one person had all the above. Two patients were classified as obese.

On average, those who had passed away due to the coronavirus had a five-day stay at the health facility where they were treated, mostly government hospitals.

The majority of people who died had underlying health issues. Just less than 50% of people who died had hypertension, and 41% had diabetes. There were a range of other comorbidities, including HIV and TB.

The province accounts for about 10% of the deaths in the country.

Data seen by the M&G shows that the Eastern Cape, which had recorded 124 positive cases by April 30, had a spike by May 6, with 309 cases. By May 26, the province had recorded 2 864 cases — the third-highest after the Western Cape and Gauteng, which had 15

864 cases — the third-highest after the Western Cape and Gauteng, which had 15 829 and 3

829 and 3 043 cases, respectively — contributing 11.8% to South Africa’s number of cases. — Thanduxolo Jika & Athandiwe Saba

043 cases, respectively — contributing 11.8% to South Africa’s number of cases. — Thanduxolo Jika & Athandiwe Saba