South Africa was among the countries — after the United States, Brazil and the Philippines — where politicians were seen as having an even higher responsibility for online misinformation than in other regions. (Graphic: John McCann/M&G)

As Covid-19 — one of the most serious public-health threats in recent history — dominates global media coverage, less than four in 10 people trust the news.

This sobering statistic comes from the Reuters Institute’s recently released report on global media behaviour, which found that concerns about “fake news” and misinformation remain high.

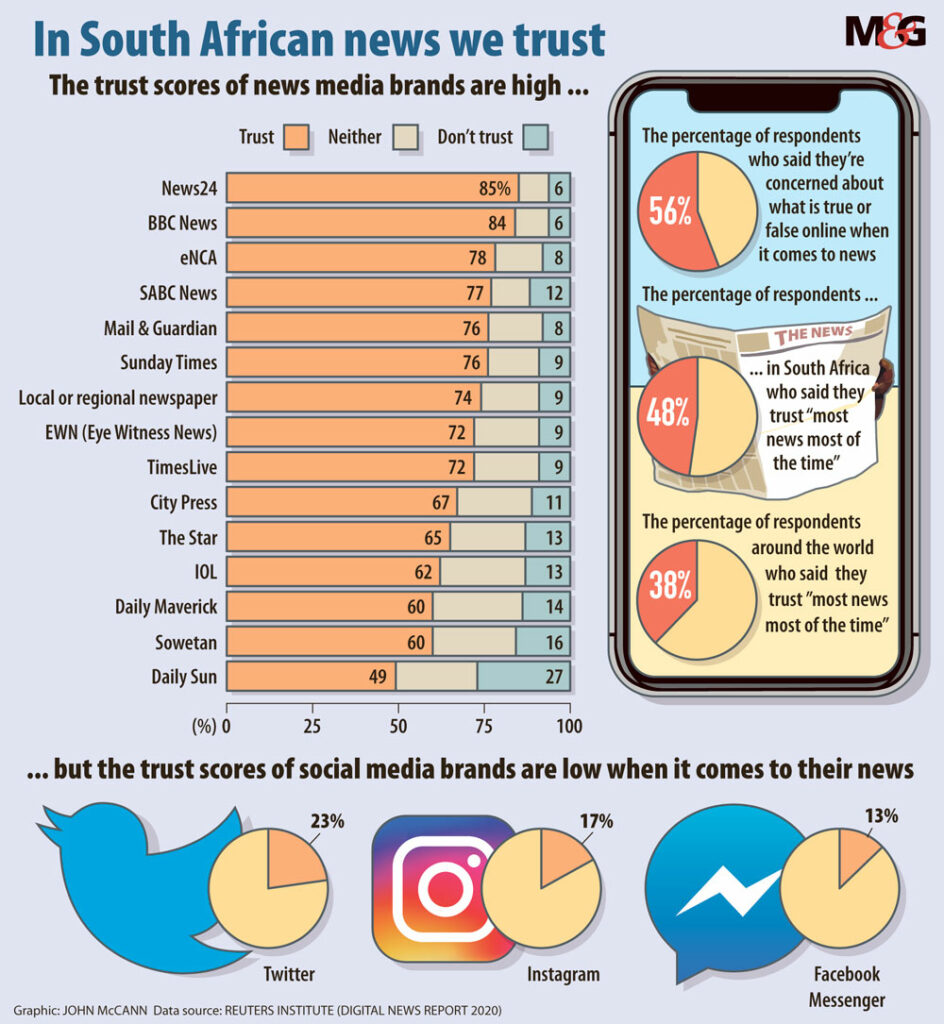

The report, which is published annually, reveals that in a poll conducted in January only 38% of the more than 80 000 respondents said they “trust most news most of the time” — a fall of four percentage points from 2019. And fewer than half of respondents (46%) said they trust the news they consume.

The survey drew responses from 40 countries, including South Africa, just before the Covid-19 pandemic hit many of them.

“The seriousness of this [coronavirus] crisis has reinforced the need for reliable, accurate journalism that can inform and educate populations, but it has also reminded us how open we have become to conspiracies and misinformation,” the report reads.

“Journalists no longer control access to information, while greater reliance on social media and other platforms give people access to a wider range of sources and ‘alternative facts’, some of which are at odds with official advice, misleading or simply false.”

According to the report, 56% of the respondents remain concerned about what is real and fake on the internet when it comes to news.

But for respondents in parts of the Global South, where social media use is high and traditional institutions are often weaker, this concern tends to be much higher. More than 70% of the South African respondents said they worried about identifying fake news.

Although South African media has built a strong reputation for independence, the report notes, political and business interference “is an increasing concern”.

South Africa was among the countries — after the United States, Brazil and the Philippines — where politicians were seen as having an even higher responsibility for online misinformation than in other regions.

Researchers conducted additional, more limited, surveys in the thick of global responses to the coronavirus pandemic to determine changes in media consumption during this period.

This survey found that news outlets struggling to survive online saw a bump in readers during the crisis. But although some countries saw significant increases in people paying for news online, across all countries most people are still not paying for online news.

“Over the last nine years, our data have shown online news overtaking television as the most frequently used source of news in many of the countries covered by our online survey. At the same time, printed newspapers have continued to decline while social media have levelled off after a sharp rise,” the report reads.

“The coronavirus crisis has significantly, though almost certainly temporarily, changed that picture.”

The reports surmises that the economic aftermath of the pandemic will likely have a lasting effect on the future of the media.

Earlier this month, the South African National Editors’ Forum took a closer look at the effects of the coronavirus pandemic on local media organisations.

Researcher Reg Rumney found that traffic to news websites increased 72% in March, just before the countrywide lockdown, and that these sites saw a 44% growth in unique browsers. Many news websites saw double-digit growth in their audience numbers in the same month.

Rumney estimated that there could be up to 400 job losses at small print-media organisations as a result of the economic pinch triggered by the pandemic, and noted that bigger news organisations have had to cut salaries to survive.

In March, the Mail & Guardian published an editorial describing the week leading up to the start of the countrywide lockdown as “one of the worst we have ever experienced in contemporary times”. The national lockdown — and the consequent uncertainty caused by the pandemic — led many companies to stop or drastically reduce their advertising spend. And the cancellation of events such as live concerts and soccer matches also meant advertising revenue from those sources dried up.

In his presentation this month, Rumney said the coronavirus crisis “has made it more urgent than ever to get readers to pay for online news”.

Read the report below:

Reuters Institute Digital N... by Mail and Guardian on Scribd