President Records Ltd presents the band Matata in London, 1971. (Copyright: President Records Ltd)

Walking through the streets of Nairobi in the 1990s, it was (and still is) not uncommon to hear club music blaring from the speakers in shops or matatu minibus taxis. As DJs played records in the clubs, a tape would roll in the deck recording as one song segued into the next, with the DJ occasionally providing a running commentary. The master tape would then be “dubbed” into thousands of copies, to be sold lucratively as cassette tapes. This trend had begun at the height of the disco era in Kenya in the 1980s when younger commuters, especially school children, would board only the most hi-tech matatus.

Meanwhile, discotheques were all the rage in Nairobi, and there were many to choose from, all with catchy names like Lipps, Visions, Beat House, Dolce, Club Boomerang, Zig Zag and the Carnivore Simba Saloon. In the mid-1990s, the government made a decision that would greatly alter the social and club culture in Nairobi: prices of alcoholic drinks, which had hitherto been regulated, were now left open to market forces, and establishments were free to set their own prices. This decision had a profound effect on club culture. Soon thereafter, Nairobi nightlife was transformed and partygoers shifted their loyalty to clubs and lounges like The Klub House at the Parklands Shade Hotel, which offered music and so much more.

No longer was there any reason to pay a cover charge, as had been the norm at discos. Of course, not all the discotheques shut their doors. In fact several, like the Florida Club, Dolce, and the Simba Saloon at the Carnivore, remained in business. They survived through a combination of strong branding and an ability to respond to the new challenge in the market by offering unique entertainment menus such as cultural theme nights.

The car park where Florida Nightclub used to be in Nairobi. (Photo: Stefan Schneide)

The car park where Florida Nightclub used to be in Nairobi. (Photo: Stefan Schneide)

The Carnivore, with its signature Simba Saloon, was a club [and] restaurant that boasted a “beast of a feast” offering a variety of meats, including wild game. By the late 1990s, the Carnivore ushered in a new era of clubbing in Nairobi by zoning the music scene with different genres on different nights, thereby stretching party days from weekends to weekdays. Hence, for example, bhangra nights on Fridays pulled in a predominantly Indian clientele; whereas the Sunday evening soul nights were aimed at a mature crowd nostalgic for the music of the 1960s and 1970s. A mature and fairly sophisticated racially mixed crowd graced the jazz night. Other varieties would develop including rock and reggae nights. The Carnivore also hosted the National Disco Dancing Competition.

Theme nights in Nairobi, featuring live performances of music from different regions of the country each month, were first witnessed at the Panafric Hotel in 2000. The Mugithi Night was headlined by popular musicians from Central Kenya like Queen Jane and Musaimo. Coastal rhythms would take centre stage on the Bango Night with saxophonist Joseph Ngala. And benga musicians from Nyanza were the main attraction on a Malo Malo Night. The Carnivore, ever quick to pick up on new trends, started offering a platform for a version of benga made popular by Okatch Biggy — an artist who was a product of the clubs in Kondele, the area at the heart of the live music scene in the lakeside town of Kisumu.

Okatch Biggy had become a national sensation in the late 1990s, and his performances alongside his band, Heka Heka, at the Simba Saloon livened up the normally quiet Thursday nights in Nairobi. Music that preserved tiny pubs was now being embraced by the urban elite. The Carnivore held its first Ramogi Night, for music in the Dholuo language, in 2003, featuring Musa Juma and his Orchestra Limpopo International, playing rumba hits like Maselina and Hera Mudho [love is blind]. Juma had moved from the Blaze Club into the city’s Eastlands area.

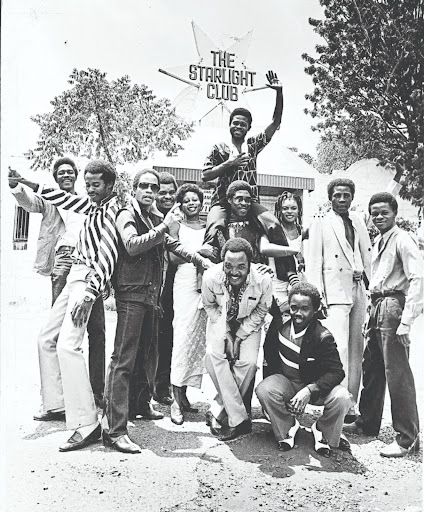

Orch Virunga in front of Starlight Club, Nairobi, 1982. (Courtesy Spector Books)

Orch Virunga in front of Starlight Club, Nairobi, 1982. (Courtesy Spector Books) By the 1990s, the live performance scene in Nairobi had not quite returned to the peak of its heyday, in the 1970s. However, there was a flicker of hope that some significant changes were afoot in the music business. These changes cannot be viewed in isolation from other dramatic shifts in the country, particularly in radio and TV, which up to the early 1990s had firmly been the monopoly of the state. The government had ceded control of radio and TV, allowing the licensing of private stations, so now there was a lot more airtime to accommodate the creative arts, especially music.

And just as had happened during the various boom periods in Kenyan music since independence, music was again attracting interest from the big corporations. Fans long accustomed to poorly organised, chaotic concerts were now suddenly getting value for their money with high quality sound, bigger performance stages, and cutting-edge urban music. For example, Beats of Season, which had begun in 1995 as an open-air live music festival received sponsorship from Tusker, a beer brand from Kenya Breweries Limited. A record 10 000 fans turned up at Nairobi’s Carnivore Grounds for its 1999 edition.

The same year, the first Benson & Hedges Gold and Tones concert took place in Kenya at the Impala Grounds where the new generation rappers, Kalamashaka, were the star attraction. The Guinness Festival on the other hand, took musicians like Jah Key Malle, Mercy Myra, Bebe Cool, Zannaziki, Gidi Gidi Maji Maji, and Poxi Presha on tour to perform before crowds in major towns like Mombasa and Kisumu. The satellite radio company Worldspace Corporation introduced the Ngoma Nights [dance nights] every month at the Carnivore, where musicians like Them Mushrooms, DO Misiani, and Sukuma bin Ongaro performed. This trend of live music has continued up to today, with Blankets and Wine, run by Muthoni The Drummer Queen, as a defining event. Opportunities were also opening up in advertising as Ting Badi Malo [raise your hands in the air], the hit song by rappers Gidi Gidi Maji Maji, became the soundtrack to a TV commercial.

Jaaziyah Satar, Muthoni Ndonga the Drummer Queen and Karungari Mungai at the Africa Nouveau Festival in Nairobi. (Photo: Royce Bett)

Jaaziyah Satar, Muthoni Ndonga the Drummer Queen and Karungari Mungai at the Africa Nouveau Festival in Nairobi. (Photo: Royce Bett)The growth of the music industry saw the need for self-congratulation, marked by awards ceremonies, although the choice of winners has not always gained unanimous approval. The Kisima Youth Achievement Awards, started in 1994, was the brainchild of producer Tedd Josiah and his associate David Muriithi. From an event that initially celebrated achievements not only in music, but also theatre, journalism and sports, it eventually became known, as The Kisima Awards, for honouring the year’s best achievements in music. The hip-hop group Hardstone, for instance, was a very popular choice for best new performing artist during the 1997 edition, the same year that the acapella group Five Alive (which featured a young Eric Wainaina, who was to rise to fame in the 2000s as a solo artist) won band of the year.

A younger generation of musicians was imposing itself with a departure from the established rulebook. In 1997, the trio Kalamshaka got their big break during the star search at the Florida 2000 nightclub in Nairobi. Subsequently, they recorded the groundbreaking hip-hop track Tafsiri Hii [translate this], about gruesome street life. It was officially released a year later on the compilation Kenya, The First Chapter, produced by Josiah. He was to become Kenya’s maestro of hip-hop and R&B, influenced by traditional Kenyan music. Kenya, The First Chapter featured a compilation of songs by rappers. Apart from Kalamashaka, there were Gidi Gidi Maji Maji, Hardstone and Nazizi Hirji, arguably Kenya’s first female rap artist.

Kalamashaka’s single Fanya Mambo [do something], produced by Ken Ring, a Kenyan based in Sweden, became a number one video hit on the pan-African music TV network Channel O in 2001. It helped to spread the fame of the band even further. Some of Kalamashaka’s best music was contained in an album titled Kilio Cha Haki [truthful cry] in 2004. The album featured a collective of rappers from Nairobi and Mombasa, like Ukoo Flani and Mashifta, with songs on political corruption, police brutality, gun crime, poverty, abortions, rape, and murder. Such was the success of Kalamashaka, that they became the first-ever foreign guest artists to perform at the Nigerian edition of the Gold and Tones festival in 1998, before a crowd of 80 000 people.

The Hardstone album Nuttin But De Stone changed the sound of Kenyan pop music by popularising an edgy urban sound with lyrics written in Sheng, the hybrid of Swahili, English and various vernacular spoken widely in urban towns. The remix of its first single Uhiki absolutely tore up both the clubs and radio stations throughout Kenya in 1996 and 1997, playing on the memory of city revellers of the 1980s who had delighted in Marvin Gaye’s Sexual Healing, whose bass line it had shamelessly lifted. Germany-based Kelele Records released Nuttin But De Stone internationally. Multiple Grammy award-winner, Lauryn Hill, who was then riding high as a member of The Fugees, appeared as a support act during the launch of Hardstone’s CD Nuttin But De Stone in Nairobi in 1997. And in 1999, Ndarlin P and his 4-IN-1 introduced a novel rapping style, using rhymes laced with humour, mimicking the various regional accents.

Ten Cities, a book on clubbing in Nairobi, Cairo, Kyiv, Johannesburg, Naples, Berlin, Luanda, Lagos, Bristol, Lisbon between 1960 and March 2020, is edited by Johannes Hossfeld Etyang, Joyce Nyairo and Florian Sievers. This extract, on the evolution of club music in Nairobi, is the first in a series of 10 weekly excerpts.