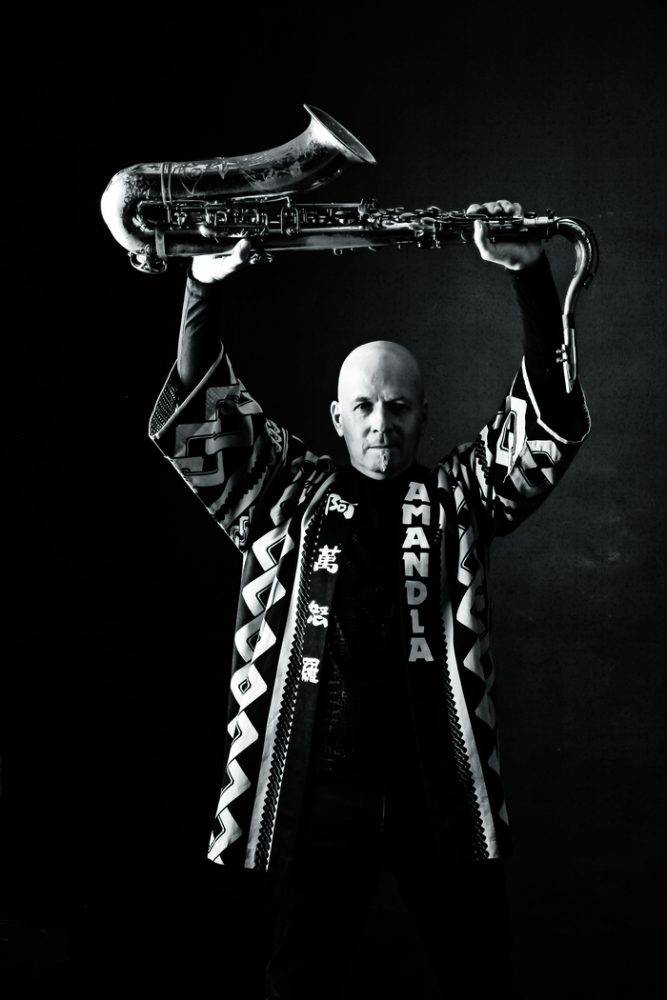

McCoy Mrubata has a launch album out for the US initiative Africarise, which showcases the continent’s music and art. (Siphiwe Mhlambi)

Two distinctive human beings and two new albums simultaneously released. Their leaders Steve Dyer and McCoy Mrubata are united by more than the fact that both play tenor saxophone.

First, their latest releases, Dyer’s Enhlizweni: Song Stories of my Heartland and Mrubata’s Lullaby for Khayoyo, are launch albums for a new jazz label group from the New York-based RopeaDope. Africarise — “focusing on the art and music of Africa” — is the child of the US label’s collaboration with City of Gold Arts and helmed by Seton Hawkins.

South African by descent, but US-based, Hawkins has been an organiser of, and advocate for, our kind of jazz for many years in his roles as music writer, director of public programmes for jazz at New York’s Lincoln Center, a jazz studies faculty member at The Juilliard School of music in the city and the host of a South African hour jazz show on SiriusXM satellite radio station.

He’s facilitated many tours for City of Gold artists, supporting the kinds of working partnerships and ideas these albums reflect.

The two launch albums have a personal meaning for Hawkins, he says. Mrubata’s album Hoelykit? “got me into South African jazz”, while Dyer’s Life Cycles was a college favourite.

Beyond that, Hawkins feels, the albums are “two interesting representations of South African jazz — one fully developed within South Africa, with Southern African artists, and one featuring a transatlantic collaboration with American artists”.

“Both Steve and McCoy are extraordinary composers and players with very different voices and styles. Opening the series with two such iconic, but very distinct, saxophone legends felt like a strong foot forward.”

The second thing the two reedmen share is a core belief about the music they make — that it’s never just about the notes but about the intention and feeling performers bring to them.

Mrubata’s nine-track Lullaby for Khayoyo (the title tune is for his grandson) is a “testament to the power of collaboration”.

The saxophonist, plus South-African-in-New-York trombonist Siya Charles, are joined by five Americans in the group Siyabulela: guitarist Gary Wittner, altoist Evan Christopher, pianist Steven Feifke, bassist Jennifer Vincent and drummer George Gray. Dig deeper, though, and those aren’t the only underlying collaborations, with the SA connections going even deeper.

As well as compositional inspiration from work with guitarist Oscar Dlamini and ’bone player Jabu Magubane, Mrubata has been collaborating with Wittner since 2014, in groups and in a duo. Vincent is his regular US bassist; Feifke’s father, a drummer, was born in South Africa and veteran Gray is an Abdullah Ibrahim band alumnus.

Mrubata recalls how everybody showed passionate interest in how South African compositions should sound: “I’ve been sharing with Gary music from [guitarists] Allen Kwela and Billy Monama for a long time. In studio, we all had intense conversations about feel, about whether an idea felt too Afro-Cuban or South African — and what that really meant.”

That sharing bears fruit, for example, in a track like Oh Yini (a tribute to saxophonist Winston Mankunku Ngozi) where the collective leans gracefully and seamlessly into South African idioms that simultaneously evoke the Coltrane place both Mankunku and Mrubata come from.

It’s even more marked in Ezilalini, inspired by Mrubata’s father’s funeral and the polyphonies of village song. There, the reedman says, “I asked them to simply ‘play what you feel’.” The track enacts the idea behind it in the free, full textures of a live, collective gathering.

That concept of individuals collectively creating something new also infuses Enhlizweni. The album represents, Dyer says, “chapters in a book” of his reflections about what being a South African means, after historical struggle and amid all the work that desperately still needs doing.

Rich vocal arrangements twine through half the 10 tracks.

Steve Dyer. (Joanne Olivier)

Steve Dyer. (Joanne Olivier)

“You can’t get away from voices —human and horn voices — in South African music,” he says, reflecting on a formative childhood experience of hearing Nkosi Sikelel’ iAfrika sung by a stadium crowd.

“It’s that thing of the collective — acting together and working out how the parts all fit in … and that’s true whatever the problems are.”

The album features a large ensemble, but includes, alongside Dyer, reedmen Mthunzi Mvubu and Mark Fransman; horns Sithembiso Bhengu and Sydney Mavundla; pianists Bokani Dyer and Andile Yenana; guitarist Louis Mhlanga; singer Siya Mthembu and more.

There’s a parallel to the free collectivity of Mrubata’s Ezilalini in Kindred Spirits, also a spontaneous studio take, where the seamless chorusing and generous handovers embody how Dyer sees relationships in the jazz community.

Some tracks take a Sankofa perspective on the legacy of struggle — looking back to envision the future. Ihlasele (from the struggle slogan “mayihlome ihlasele” — arm yourself to attack) reflects on the new kinds of arming and struggling required to solve today’s problems.

And Dyer flips the meaning of struggle hymn Senzeni na? (What have we done? [to deserve oppression]) by crafting a fresh lyric: “Amaphupho ephelile” (The dreams are finished — what have we done to make things better?).

There are other parallels between the albums. Mrubata acknowledges a bit of the America he’s seen in his closer Hudson Bridge, a jaunty and very South African solo tribute to the structure’s “strength and flexibility”.

Dyer acknowledges the jazz interchanges between the two countries in Transatlantic, while asserting “we also have a voice in that interchange and it’s good that voice is becoming more prominent”.

And that takes us back to the point of Africarise. “We’ll be profiling South African music to a wider audience through this initiative,” says Dyer. “So, as cultural ambassadors, we need to think about the messages and images we’re bringing.”

Mrubata agrees: “There was a time when I was trying to be a little Grover Washington clone. But Bra Winston, Bra Duke [Makasi], they showed me everything we have here.

“Now, when I’m teaching, I’m not anti-evolution or new music from elsewhere — but never suppress what comes naturally, the things you’ve grown up with.”

Those musical things are so diverse they can never be fitted into a single exoticised stereotype of “Africa”. Hawkins, while paying tribute to “the instrumental virtuosity” of today’s South African artists, is “far more struck by how distinct South African jazz’s sounds and styles are — a very extraordinary embrace of local musical traditions with jazz traditions, unique in this world”.

The label’s first two outings, much as they share a feeling, profile two strikingly individual, highly personal, ways of playing it.