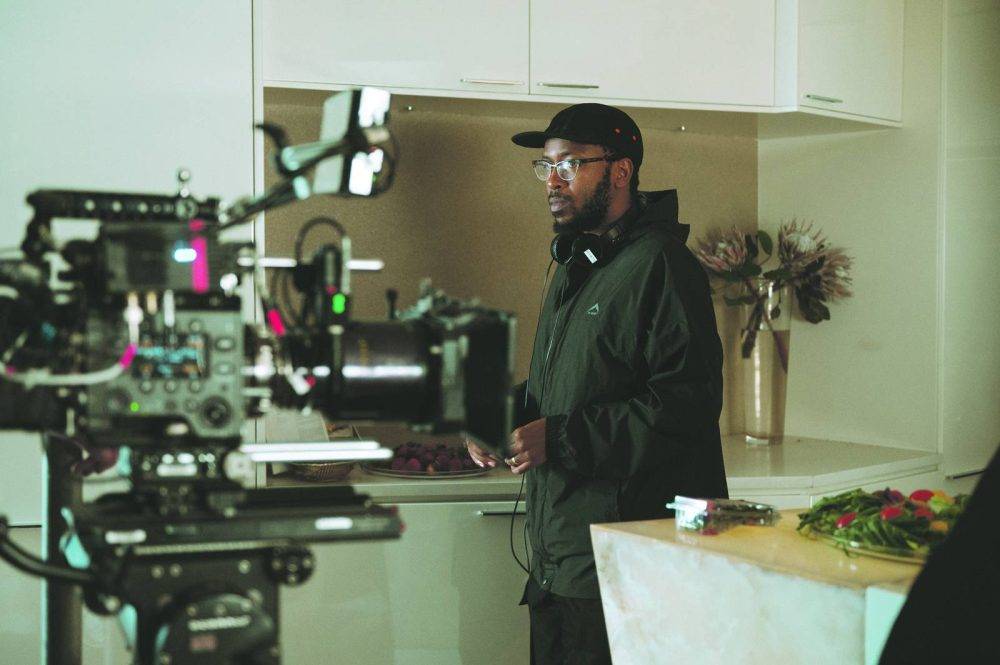

‘Electronic, less housey’: Nthato Mokgata, aka Spoek Mathambo. (Florian Spring)

We are in a Bryanston, Joburg, coffee shop called Conversations for a chat with Carla Fonseca Mokgata and Nthato Mokgata. After ordering coffee and tea, but before we talk about a new movie, new music and a new novel, I insist that Fonseca shows me pictures of their new baby.

She has a special folder with pictures of Sa-Ra Qamata who made her appearance in February — as her parents started post-production on A Scam Called Love, a romantic comedy they co-wrote and directed over 10 months across last year. Making movies is anything but romantic.

“We shot in November, December and I gave birth in February,” says Fonseca. “Yeah, it was very, very tough. We had an actor from the UK who was only here for a certain period because he was flying to America two days after our final day …

“So, we had some days, only four hours sleep … six-day weeks, for five weeks. It was a little bit mad.”

Two months later, their baby was born.

“You give birth and then some people will take three months’ maternity leave,” Fonseca says about this — literal — labour of love.

Carla Fonseca Mokgata from Afro-house group Batuk. (Gabrielle Kannemeyer)

Carla Fonseca Mokgata from Afro-house group Batuk. (Gabrielle Kannemeyer)

“Whereas, sure, I wasn’t going to an office, but I was working. You know, in a hospital bed with my laptop … we’ll never do it again. I’ll never be pregnant and make a film at the same time.”

She giggles. “Lesson learned.”

It is no surprise that little Sa-Ra is gorgeous, with — in every sense of the word — attractive and talented parents like hers.

Mom is a multi-disciplinary artist — director, writer, actress and musician — and Dad is better known under his musical nom de plume, Spoek Mathambo, globally recognised for his genre-fluid and innovative township tech, as well as his animation and documentary films.

“Oh, she’s a sweet little baby,” coos Fonseca as she flicks to a specific pic on her cellphone to show me. “There’s a smile …”

Mokgata’s smile is even wider as he looks on.

A Scam Called Love will make history as the first MGM Amazon rom-com to emerge from South Africa. Made in collaboration with Wolflight, a Los Angeles production company, it is the Joburg couple’s first commercial production.

Set to premiere in the first quarter of next year, the film will have a national release across Ster-Kinekor and Nu Metro in March, followed by a global launch on Amazon Prime.

The film tells the story of Zola, a determined South African chef whose US visa is about to expire.

In a desperate gamble, she enters into a fake marriage with her carefree American co-worker Julian.

Together, they navigate a hilarious and heartwarming journey to convince both US immigration, and Zola’s conservative South African family, of their love.

With a cast including Thando Thabethe, Motlatsi Mafatshe, Brenda Ngxoli, Didintle Khunou, Fezile Mpela and UK-based actor Tobi Bamtefa, A Scam Called Love captures the complexity of modern relationships while celebrating the cultural vibrancy of South Africa.

Wolflight — two South African producers, Roelof Storm and Hannes Otto, and their American partner Will Seefried — invited Fonseca and Mokgata to pitch this romantic comedy, with the skeleton of the story already there.

The couple is the embodiment of that old cliché of how people who are exactly on the same wavelength finish each other’s sentences — in fact, they’re like a well-timed comedy duo, not interrupting, but rather complementing, each other.

History in the making: Scenes from A Scam Called Love, a movie by Carla Fonseca Mokgata and Nthato Mokgata, which will be the first MGM Amazon rom-com to emerge from South Africa, when it is released online — and on the big screen — next year.

History in the making: Scenes from A Scam Called Love, a movie by Carla Fonseca Mokgata and Nthato Mokgata, which will be the first MGM Amazon rom-com to emerge from South Africa, when it is released online — and on the big screen — next year.

So, what was it like doing a romantic comedy, I ask them. Is it something you normally watch?

“No, it’s definitely not my genre of choice,” says Fonseca. “I’m more of a thriller girl — thriller drama.

“At first, it was quite daunting, but then, really exciting. I enjoyed the comedic side. I enjoyed writing comedy. I discovered that there’s a lot of thrill in writing comedy.”

Mokgata adds: “I thought you would never write comedy. Carla’s political work is very serious.

“I mean, her other film projects are very serious, weighted work. And the flippant, the silly, the frivolous …” He shakes his head.

“So, it was a challenge, but I actually really enjoyed it,” she picks up.

“But we definitely needed to find some twist in it … to satisfy that side of me. And so, we added some thriller elements to the rom-com.”

Him: “I mean, beyond adding layers, my interest was to make it cinematic. And to make it a credible work of cinema.

“For it to be entrenched in South African pop culture, but also to work on different levels of form and subversion. And, yeah, just different ideas that we wanted to tease out and to play with the form.”

Not something we see on local screens, they believe.

“South African rom-com is in a shit place,” says Mokgata firmly.

“It’s in a very, very bad place …” adds his partner.

“And it doesn’t have to be,” continues Mokgata.

Fonseca: “It’s really like just one script is being passed around.”

“So, I think it was within parameters to see how to break that mould,” Mokgata adds.

Fans of his Spoek Mathambo persona will be familiar with his quirkiness, so no surprises when he confirms: “I really looooove comedy. But it has to be dark. I don’t like silly. I like smart.”

No thanks then to The Wayans Bros. and The Naked Gun.

“If you ask me what’s my favourite South African TV show, I say the sitcom Emzini Wezinsizwa.” It is where his stage name Spoek Mathambo comes from.

For Mokgata, South African comedy should be ridiculous, because it’s part of the culture.

“What can we express from the culture? What can we subvert? What can we make fun of?” are his guiding principles.

Fonseca explains that casting was difficult. “Because we needed to find people who are naturally funny,” she says. “The script needs to be funny … but we can’t be solely dependent on the text.”

“Everyone needs to understand funny,” adds Mokgata. “Even the straight man needs to know what funny is.”

Fonseca: “Oh yeah, and they need to … improvise. Sometimes we wouldn’t call cut just to see how far they can go. How far they can take it. And a lot of the time they would …”

In A Scam Called Love comedian Trevor Gumbi is “excellent at that. But also, wild. He’ll say the wildest things,” says Mokgata. “There’s some things that aren’t PC …”

“And Thando Thabethe as well … I don’t know if she’s had an opportunity [before] to show how funny she is,” wonders Fonseca. “She’s really funny and … Brenda Ngxoli as well.”

When it came to division of labour in making the film, Fonseca and Mokgata played to each other’s strengths.

“There’s a level of expertise and skill in particular areas,” he says. “Like Carla from her stage directing. As far as how to go there: subtext, depth of emotion, subtlety.

“Like, I would default to her level of expertise.”

“Yeah, the way we split it was that I would communicate,” she adds, “with the actors and really do the blocking. You know that character moves from here to here. This is how we’re going to design it.”

Mokgata: “Then there is this other stuff. Cultural stuff. Comedy stuff, hip-hop stuff, cultural stuff that Carla won’t …”

“Yeah, I prefer not to touch. That’s his department.”

They strike me as refreshingly ego-free as Mokgata explains their scriptwriting: “We would take … re-writing scene, re-writing scene, re-writing scene, just go back and then swap them around.”

“And then I’d edit his and he’d edit mine,” she says.

“Yeah, the writing process was very smooth, very exciting.

“I look forward to writing more scripts together. And the directing process as well — as long as we split those. And it worked seamlessly.”

Film has always been a medium that both have appreciated and wanted to do, with Mokgata having worked in documentaries and Fonseca studying drama at UCT.

But the pair learned about the cinema the hard way.

In 2017, Fonseca and Mokgata made their first film together, an arthouse movie called Burkinabè — a person who is from Burkina Faso.

“Written, directed, produced, edited, by us,” she says with a smile. “Too many hats — I acted in it as well.”

They launched the film in 2019 at Fespaco (the Pan-African Film and Television Festival of Ouagadougou) in Burkina Faso.

“They have more cinemas than they have churches,” says Fonseca. “It’s just incredible. You walk around the corner and there’s a cinema.

“You walk around where there’s a football field and a whole lot of people, kids on bikes, watching a big screen that’s just been put up there.”

It all went well with the screening of Burkinabé until the Q&As afterwards — after all, Burkina Faso is regarded as the cinema capital of the African continent, with a highly educated cinema public, and on top of that, a cinema intelligentsia.

First there were the deeply technical questions. But then it got tougher, as Fonseca recalls. “Some people would ask, ‘You’ve never studied film. What audacity do you have to make a film? How dare you?’

“But really, I mean, some of the greats never went to film school.

“And, if you start from writing down the first word through to editing, those two years of working, that’s university. There’s nothing more ‘school’ than actually doing it, needing to finish this thing.”

“And shooting this project, part in French, part in Mooré [a local language in Burkina Faso] …” Mokgata adds with a smile.

“Communicating with people who don’t understand English,” she says.

“Us being the only South Africans on the crew,” he adds.

Her: “Yes, it was very weird.”

Him: “Yes, so when you ask why you do it, part of it is the challenge. We have these dreams.”

She chuckles: “We have audacity!”

Fonseca and Mokgata met in 2010 through mutual friends in Cape Town. She had just completed her studies and he was already the talk of the underground electronic scene.

“I was also a huge Spoek Mathambo fan,” she smiles. “So, I probably stood there and just greeted.”

Three years later they met again in Mozambique.

“And then, shortly after that, Ntatho asked me to come to the studio. I thought I was just going to watch him play music. But then I was given a mic.”

Mokgata explains: “I had seen a play that she did in Maboneng. It was kind of really crazy,” he chuckles. “No stage. It’s experiential. You have to walk around and move through this whole building. Different scenes, different characters.

“It was really good. And no … no singing. Obviously, a lot of vocal projection, storytelling, different accents, different scripts.

“And I thought, ‘Whoa, this would be really great.’”

And so, their Afro-house group, Batuk, was born — their first releases came out in 2016. They toured across Africa and gained many fans throughout Europe with their club-friendly beats and politically conscious lyrics.

The group’s pan-African electronic music, using different languages, from across different cultures and with different rhythm concepts, was linking people and breaking down xenophobia.

“And then there’s the feminist side,” Fonseca says, “We have some songs that speak about the woman’s body and that it’s not a property. I mean, girls would go crazy.”

I ask what it was like being in Batuk. Fonseca corrects me with a smile.

“What is it like? Because we’re still working together. We released something last week.”

Batuk have been releasing music digitally on streaming platforms. Some people, especially Japanese fans, kept buying their CDs.

“They kept us alive during Covid, when things were like, bad-bad, but we’re always getting physical CD orders,” says Mokgata.

I ask them to describe the new Batuk music to me.

“Electronic, less housey,” reckons Fonseca.

“We’re not playing in the club,” adds Mokgata.

“So, we can kind of do what we want and experiment in some ways. We’re making music that we also want to listen to. As opposed to … before when we were building songs specifically for the club, for big sound systems.”

So, in between the new film, new music and new baby, Mokgata found the time to write a novel titled Ghost in the Drum, which has just been published.

How, I ask him, but Fonseca replies.

“He was staying up to make sure the milk bottles were warm [for the baby]. You know, Nthato would be working crazy hours of the night, and making sure the bottle is ready at certain times at night.

“And I think that’s where he goes into that world and is working constantly.”

Mokgata picks up the thread.

“I’ve been writing scripts for the last five years. I’m very diligent in writing these scripts.

“The only difference is with the script someone can tell you, ‘No, we don’t want to make that. That’s not in our slate. That’s not in our budget.’

“Whereas, here, I thought, ‘What the hell? I’m doing the work. I’ve got these stories. Why not put it into the form that I love independently that I can do?’”

In Ghost in the Drum, Mokgata pulls back the curtain on the raw, unfiltered reality of fame, addiction and self-destruction in South Africa’s dynamic township music scene.

The novel is a satirical yet very realistic, kasi-based story that dives into the price of ambition and the fragility of genius.

Tisela, Pretoria’s rising star, is the voice of a generation caught between rebellion and redemption.

“The truth is I’ve been trying to write a novel for a very long time,” says Mokgata.

“Since high school … from then on, the challenge of writing the novel just kept kicking my ass.”

He tried to co-write it with a friend but that did not work out.

“And I quit … something that I wanted to do for so long. But it was more difficult than making music.

“It was more difficult than making a film. It was more difficult than animation. It was just more difficult here, because it’s just you focus on your mind, and you battle against your mind.”

It is probably working on the film that got Mokgata focused to write Ghost in the Drum.

“On the film, there’s a lot of external investor influence. It’s creation by committee. Whereas with this book I could get back to what started all my creativity.”

We go back to A Scam Called Love, to where the film started in the beginning of last year.

“I was saying that we started this process before I fell pregnant,” Fonseca recounts a discussion with the producers. “And when our film comes out, our child will be one.

“Our producers keep saying, ‘What do you mean?’

“I said, ‘Yeah, this is how long it’s been.’”

I ask Fonseca and Mokgata if they are not tired of the film, having worked on it for so long.

“I’m tired of holding onto it — I really just wanted to share it.”

“It’s like giving birth?” I ask.

“It’s time to pop. Jeepers, man.”

Mokgata adds: “And a lot of films never come out. There’s a lot of stillbirth films.

“So, the big anxiety is really for us to package it at the best level that we can and share it at the best level that we can.”

Fonseca: “But the great thing is that it’s done. It’s done.”

“No, it’s not about it being done, it’s about it being out,” he says.

“Like I said, so many people have films that are done. I have friends who have films from 20 years ago that have never come out.”

Fonseca has the last word: “This one’s definitely coming out. Yes, it’s coming out.”